The surprising call of Matthew

There's a question that pervades Matthew's Gospel: who's in and who's out?

Today is the feast of St. Matthew, the apostle and evangelist who composed the Gospel account that bears his name. We are also in the middle of lectionary year A, which, for the most part, follows Matthew. That means that we've spent the last nine months hearing him tell the good news of Jesus with a perspective that reflects both his own experience and that of the Christian community of which he was a part. And, if we've been listening carefully, we've noticed that Matthew's version repeatedly conveys a tension between who is in and who is out.

Matthew is the only one who tells us the story of the Gentile wise men from the East who saw the infant king's star and followed it to Bethlehem. Matthew is the only one who describes the kingdom of heaven as a field sown with good seed and later by an enemy with weeds and who tells us that both must grow up together until the day of judgment, when the weeds will be separated out and thrown into the fire. Matthew's Jesus is the only one who tells the parable of the net with all kinds of fish—some clean and some unclean—that have to be separated before they can be eaten. Matthew is the only one who shares the parable of the laborers in the vineyard, this Sunday's gospel lesson, in which even those who came at the last hour get paid as much as those who worked all day. Matthew is the one who, when he recalls the story of the Gentile woman who begged Jesus to heal her daughter, describes her as a "dog" without using the semi-affectionate diminutive form of the word, a softer sounding "puppy," which the other accounts use. Matthew's account is the only one in which Jesus orders his disciples to go nowhere among the Gentiles or Samaritans but only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.

In other words, in ways that aren't so clear in the other Gospel accounts, Matthew shows his reader that there's always an underlying question about what sort of person gets salvation and what sort of person gets left out.

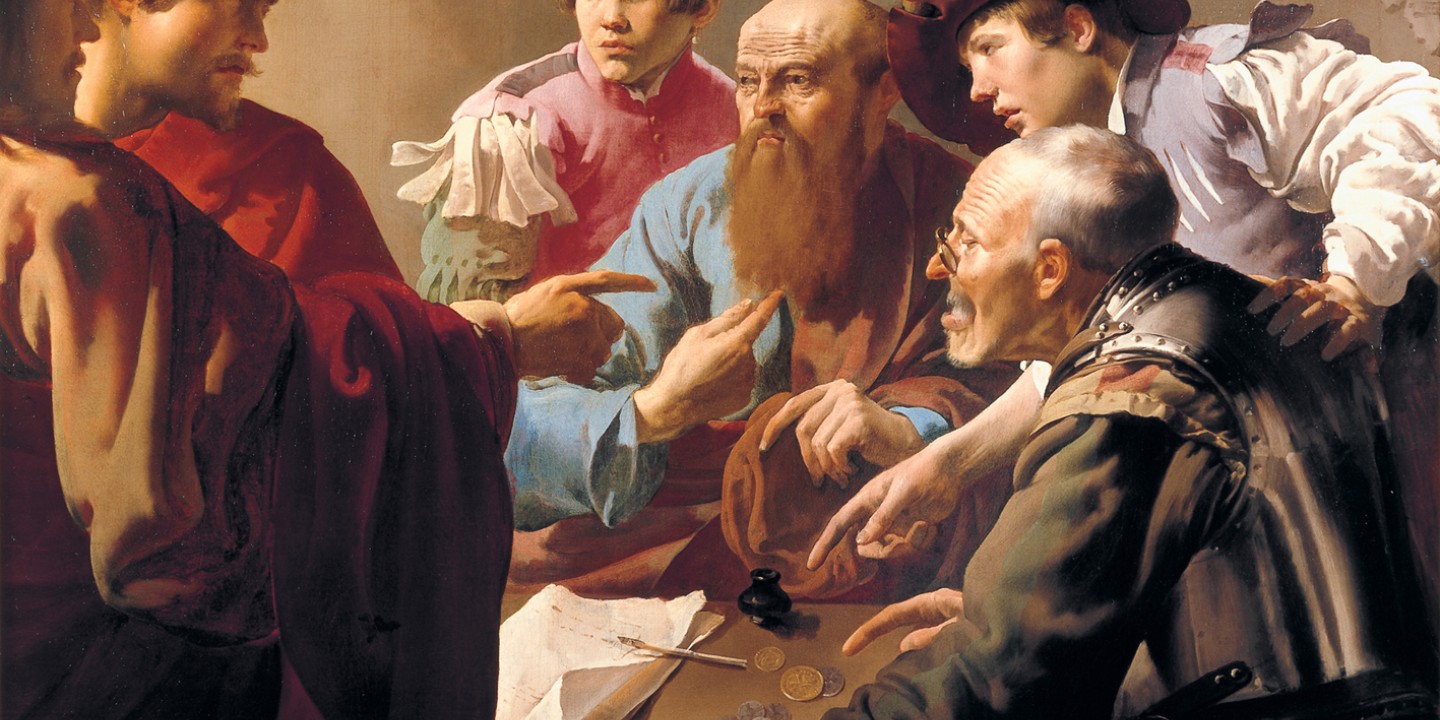

I wonder whether Matthew's own calling in Matthew 9 has something to do with that. "As Jesus was walking along, he saw a man called Matthew sitting at the tax booth; and he said to him, 'Follow me.' And he got up and followed him." As a tax collector, Matthew was working for the enemy of God. He was responsible for getting money from his fellow Jews and giving it to the Roman Empire, and his own salary came from commission—which means he was motivated to squeeze every penny from them. It's not an accident that in the Gospel accounts the label "tax collector" is associated with "sinner" as if they were interchangeable. That's the life Matthew lived—rejected by his people, rejected by his faith, rejected by his God. And then Jesus comes along and says, "Hey, tax collector! Follow me!"

We see in the verses that follow that Jesus was keeping company with other tax collectors and sinners and that this choice got under the skin of the religious elites. "Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?" they asked his disciples. Jesus replied directly to them, saying, "Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick." That's the teaching that the Pharisees need to hear. They need to learn what it means for God, who desires mercy not sacrifice, to draw sinners to himself and not righteous people. But how does the truth of God's choice of sinners like Matthew the tax collector shape him and those like him? We see explicitly what that choice does to the religious insiders. What does it do to those who are called?

I wonder which was harder to believe: that Jesus would eat with sinners like that, or that Jesus would eat with sinners like me or you or anyone else whom Jesus calls. Who had the harder time grasping the reality of that call, the Pharisees or Matthew? Which is easer: to mock Jesus for hanging out with sinners, or to get up when he calls and trust that even you have a place at the table?

The Gospel accounts spend a lot of time describing the elites' reaction to Jesus' company, but we never get the first-hand account of what it felt like to be called from a place of sin and rejection into a place of forgiveness and reconciliation. Unless we count Matthew.

There is a tension in our lives between who is in and who is out. We feel it. Even those of us who have lived so-called "good" lives, who go to church, who pay our taxes, who kiss our mothers, and who say our prayers, even we wonder whether Jesus could really be calling us. "Who me?" we ask, when he points his finger at us. "Me? Why me?" we ask. Over and over, Matthew brings us to that tension. Who belongs—the dog who eats the scraps that fall from the master's table? What fish get thrown away? What weeds get gathered and burned? What Gentile stargazers, who know less about Israel's God than they know about Pisces and Leo, are invited to see the king?

Today we celebrate not only Matthew, the tax collector who was invited to join Jesus and who became an evangelist, but also the tension that comes from wondering whether we, too, might belong to God. Throughout his account, Matthew invites us to ask those sorts of questions—who belongs? do I?—because he felt that tension himself. He discovered what it means for a sinner to be welcome at God's table, and he invites us to do the same.

This post originally appeared at A Long Way From Home