New travel ban still anti-Muslim, critics charge

(The Christian Science Monitor) In the eyes of critics, President Trump’s executive order on travel to the United States by refugees and nationals of six Muslim-majority countries is still an unconstitutional Muslim ban.

The new order was scheduled to take effect March 16 but was stopped by two federal judges.

U.S. District Judge Derrick Watson of Hawaii commented in his ruling that “a reasonable, objective observer . . . would conclude that the executive order was issued with a purpose to disfavor a particular religion.”

The new executive action exempts U.S. green-card holders and other foreigners in possession of a valid visa, and it no longer singles out Syrians for indefinite suspension from entry.

The revised order also allows immigration officials to issue visas to individuals from the six temporarily banned countries on a case-by-case basis, for example, for students and work visa holders or children and individuals requiring urgent medical care.

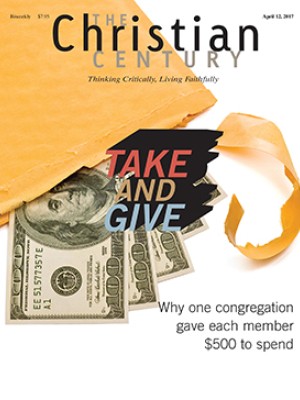

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In addition, the new order no longer prioritizes the resettlement of religious minorities—Christians, by and large—from the six Muslim-majority countries. That prioritization was one of the key features of the original order.

“This is not a Muslim ban in any way, shape, or form,” a senior Department of Homeland Security official said, citing as proof the fact that the ban does not affect the vast majority of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims.

Some say the revised travel order would still be counterproductive because it would raise tensions with Muslim countries whether or not they are affected by the ban, while playing into the propaganda efforts of terrorists. [Others have pointed to the executive order’s request for a report on the number of honor killings carried out in the United States by “foreign nationals” as stoking stereotypical views of Muslims. Scholars consider honor killings, a form of violence against women, as stemming from cultural rather than religious norms.]

The six countries included in the 90-day travel ban are Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Officials said Iraq was dropped from the list of countries subject to a 90-day travel ban because of its strides in recent weeks to address shortcomings in citizens’ documentation.

Like the original order, the new executive action suspends the refugee resettlement program for 120 days, while reducing the number of refugees to be accepted by the United States this fiscal year from 110,000, as set by President Obama last year, to 50,000. Trump administration officials say that about 35,000 refugees have already been admitted since the beginning of the fiscal year in October.

Implementing the revised immigration order could be as problematic as the previous one, which was suspended by a federal judge in February. That suspension was subsequently upheld by a federal court of appeals.

After Trump’s initial order was halted by federal courts, support for the ban began to wane among most religious groups, according to a survey by the Public Religion Research Institute. Support from Catholics, mainline Protestants, and religious minorities dropped. Among white evangelicals, however, support increased.

Bob Roberts, pastor of the 3,000-member NorthWood Church in Keller, Texas, has grown concerned by what he sees as Islamophobia among fellow evangelical Christians.

“Evangelicals have mixed their faith with the state, making a kind of religious nationalism,” said Roberts, who has worked with Muslim leaders around the world to foster interfaith fellowship. “They see it as ‘taking back America,’ as stopping the Muslims from taking over America.”

For historians of religion, this wariness of outsiders in many ways goes back the country’s early Puritan settlers.

“The notion of a nation with more visible Muslim communities doesn’t comport with ‘the city on a hill’ or this notion that America is and always has been a Christian nation,” said Randall Balmer of Dartmouth College. “And in some ways, this has happened once before.”

During the period of industrialization near the turn of the 20th century, many Protestants reacted with alarm to the influx of Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox immigrants.

“The response on the part of many evangelicals was to lapse into apocalyptic language and an interpretation that saw the country on the verge of collapse,” Balmer said.

Today, 76 percent of white evangelicals approve of the temporary ban on refugees from the six countries, according to another recent survey by Pew Research. That compares with 50 percent of white mainline Protestants, 36 percent of Catholics of all races, and 10 percent of black Protestants, the survey found. Overall, about four in ten Americans currently approve of the controversial immigration ban.

Christian leaders, both evangelicals and others, many of them involved in overseas Christian ministries helping refugees in Muslim countries, have objected to the ban.

[Linda Hartke, president of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, said in a statement that the new order “still prevents us from undertaking lifesaving work during the most critical time for refugees and displaced persons in human history.”

On March 3, three days before the new order was signed, Church World Service and the National Council of Churches launched a campaign to safeguard the U.S. welcome of refugees.

“Refugee resettlement is one of the most cherished traditions upon which our country was founded and plays a critical role in U.S. diplomacy and foreign policy,” the ecumenical declaration states.

Signers of the declaration, including mainline denominational leaders, noted that Church World Service has resettled refugees for more than 70 years.

The groups wrote that “it is imperative that we speak out against the notion that refugees are a threat to our safety—they are not.”]

A version of this article, which contains reporting from Religion News Service and the Christian Century staff, and was edited on March 27, appears in the April 12 print edition under the title “New travel ban still anti-Muslim, critics charge.”