My mother land of Puerto Rico is in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. Crippling debt has ravaged infrastructure and social institutions. While media has largely presented this as an abstract economic problem, the real effects of this catastrophe are witnessed in what Ada María Isasi-Díaz calls lo cotidiano: the everydayness of life. They are witnessed as one walks through my mother’s pueblo of Barranquitas and notices the overwhelming amount of closed and/or abandoned Puerto Rican businesses. They are witnessed when teachers have to choose between using the lights or computers in their classrooms. It will be witnessed when, in accordance to the PROMESA Bill passed this summer, 20-24 year old Puerto Rican workers will struggle on a minimum wage of $4.25 per hour. And though the history that brought us here is directly tied to white, U.S. Protestant denominations, many Protestants in the United States are unaware of this story.

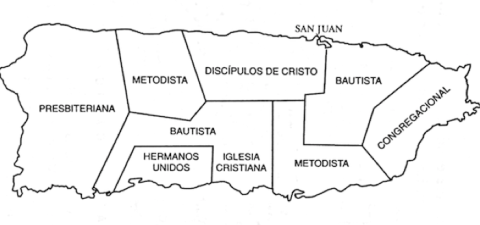

The 1915 issue of Fuente: The Missionary Review of the World featured a map of Puerto Rico carved out to depict “zones of influence” for nine major Protestant denominations: Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Congregational, United Brethren, Christian Church, Lutheran, Missionary Alliance, and Disciples of Christ. Each zone was established in an 1899 committee agreement between these groups. That year leaders from each met in New York City to discuss how to engage the “new mission field” acquired in the Spanish-American War without “stepping on each others’ toes.” Their solution was to set parameters for where each particular denomination could evangelize and establish institutions. Presbyterians took the West, Disciples the Mid-North, Baptists parts of the island’s center, etc.

Their collective mission was clear. As the United Brethren Church of Christ officially reported, their agenda was:

“Inaugurar un trabajo que asegure la americanización de la isla, así como su entrada a las alegrías y privilegios del discipulado cristiano…debemos inaugurar una escuela y así alcanzar cientos de niños que puedan ser formados por medio de esta agencia para la responsabilidad de la ciudadanía americana.”

“To inaugurate a work that assures the Americanization of the island, similar to the work of welcoming individuals into the joys and privileges of being a Christian disciple...we should inaugurate schools that will reach hundreds of children who can be formed through these institutions in the responsibilities of being an American citizen.”

Missionary impulse, articulated as “spreading the gospel,” was to push dominant U.S. American (read: white, Anglo, Protestant) values of individualism, separation of church and state, English-language, and consumer capitalism on to the (allegedly) “un-churched” and “uneducated” Puerto Ricans. Protestant missionaries did so by working alongside U.S. corporations to integrate Puerto Ricans into the capitalist market, founding hospitals that later became sites for eugenically testing Puerto Rican women, and by establishing schools that demanded English-only of Spanish-speaking students. While many missionaries claimed “good intentions” in sharing what they deemed “salvific,” the reality was that their ‘gospel’ was tied to dominant U.S. American values which they embedded in social institutions.

Because the values promoted were tied to “the gospel,” they were viewed as “salvific” and thus as ushering in a new era of “progress” for Puerto Ricans. According to Ramón Grosfoguel this “message of salvation and progress” quelled nationalist sentiment and masked the United States’ colonial agenda. Indeed, if U.S. ideals and institutions were painted as salvific and “progressive,” U.S. corporations taking over 60% of Puerto Rican land, U.S. appointed governors quelling Puerto Rican attempts at self-governance, and U.S. military officials placing Puerto Ricans on the front lines of U.S. wars could be read as “ethically altruistic” or even as part of a “divine plan.” And in the early twentieth century it was. Samuel Silva Gotay notes that as early as 1906 many converted Protestant Puerto Ricans called U.S. entrance into Puerto Rico part of “God’s divine plan.” By 1914, some converted Puerto Rican Protestants were even asking when “Tio Sam” would grant Puerto Ricans the “gift of American citizenship”! This is not to say there weren’t detractors—indeed many questioned both Protestant and U.S. encroachment on the island. Yet, particularly in the early twentieth century, these were few and far between. For this reason, Silva Gotay calls Protestant missionaries the assimilationist arm of U.S. colonialism.

Today, many individual Puerto Ricans express a vibrant Protestant faith that cannot and ought not be dismissed. Native American theologian Tink Tinker suggests the same about First Nations Christians noting that faith is complex, personal, and speaks to a reality beyond ourselves. As a result, faith cannot be dismissed merely as imposition or appropriation but as something much deeper. Yet, Tinker also explicitly states that faith does not dismiss historical reality. And even though today many Puerto Ricans hold deep Protestant convictions that have even led some in recent history to oppose colonialism, the fact remains that Protestant churches are historically and structurally implicated in the colonization of Puerto Rico that continues to this day. After the Spanish-American War, the United States government could not have spread capitalism, English-language, and dominant U.S. culture to Puerto Rico without Protestant missionaries. Their ability to infiltrate locally and establish institutions made them more effective at this task than government agencies. These values and institutions undergirded the the U.S. colonial project that has contributed to the present socio-economic crisis in Puerto Rico.

Those connected to the Protestant tradition are implicated in this history because it was Protestant leaders and their particular missionary impulse that aided colonial objectives. This legacy demands that we educate ourselves on the past realities and present injustices in Puerto Rico. We should look at future solutions that are being offered not by the latest iteration of U.S. colonization—guised as “benevolent saviors” on a financial control board—but by the people of Puerto Rico who daily resist colonization.

¡Que viva Puerto Rico libre!

The following is a short list of resources (from Puerto Rico and the Diaspora) to begin the process of (un)learning about the island

For more on Protestant Missionaries in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean see:

- Protestantismo y Politica en Puerto Rico: 1898-1930 by Samuel Silva Gotay

- Masked Africanisms: Puerto Rican Pentecostalism by Samuel Cruz

- On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality, and Culture by Louis A. Pérez Jr.

For more on Puerto Rican History see:

- Colonial Subjects: Puerto Ricans in a Global Perspective by Ramón Grosfoguel

- The Puerto Ricans: A Documentary History edited by Kal Wagenheim and Olga Jiménez de Wagenheim

- Puerto Rico in the American Century: A History Since 1898 by César J. Ayala and Rafael Bernabe

- Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World by José Trías Monge

For more on Eugenics and Puerto Rico see:

- Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico by Laura Briggs

- A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era edited by Paul A. Lombardo

For more on Colonialism, generally, see:

- Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldua

- The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options by Walter Mignolo

- Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon

For more on PROMESA and the Puerto Rico Debt Crisis see:

- H.R. 5278, “Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act” or “PROMESA,”

- “Protests Against ‘Colonial’ PROMESA Debt Plan Rock Puerto Rico"

- “Puerto Rico Control Board: A Dangerous Increase of Colonialism or Vital Protection from Wall Street?”

- “Protests Erupt in San Juan as Obama Forms Unelected Control Board to Run Puerto Rico"

For more on Puerto Rican resistance to colonization see:

- “The Last Colony,” (documentary)

- Defend Puerto Rico, (Activist Group)

- #BlackLivesMatter, Puerto Rico (Activist Group)

- “Hundred Shut Down Puerto Rico’s Largest Wal-Mart,” (News Story)

- Partido del Pueblo Trabajador, (Political/Activist Organization)

- When I Was Puerto Rican: A Memoir by Esmeralda Santiago

- Boricuas: Influential Puerto Rican Writings edited by Roberto Santiago

- Between Torture and Resistance by Oscar López Rivera

- The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation by Darrel Wanzer-Serrano

- Prophesy Freedom: A Puerto Rican Decolonial Theology (Forthcoming) by Teresa Delgado

- War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony by Nelson A Dennis

About the Author:

Jorge Juan Rodríguez V is the son of two Puerto Rican migrants who migrated to the United States a year before he was born. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Modern Religious History at Union Theological Seminary where he uses social theory, theology, and history to analyze linkages between religion and colonization. Follow Jorge on twitter at @JJRodV

Subscribe to Practicing Liberation Updates in order to receive periodic alerts about new posts on this blog. This is the best way to stay connected.