Reporting trips and ego trips

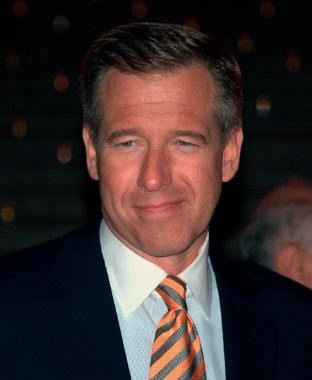

Ah, the Brian Williams imbroglio. The NBC anchor’s exaggerated (or outright false) retelling of his experiences on an assignment to Iraq, called into question and cause now for a six-month suspension without pay.

For the past week or so, the whole thing has had a lot of us shaking our heads. I’m still shaking my head.

Brian, Brian, Brian. Why?

Williams seemed a throwback to a more staid era, displaying a certain, if studied, gravitas. Seemed is apparently the operative word here. Now we find out, courtesy of Maureen Dowd, that Williams’ braggado “was a bomb that had been ticking for a while,” and that his bosses at NBC had been put on alert a year ago that their $10 million man “was constantly inflating his biography” and required “Hemingwayesque, bullets-whizzing-by flourishes to puff himself up, sometimes to the point where it was a joke in the news division.”

A couple thoughts. First, lying or exaggerating by journalists isn’t acceptable. Ever. Call me old-fashioned—and yes, I know the arguments that there is no such thing as “objectivity.” But an essential element of journalism is being able to look at things with a bit of distance, without oneself at the center of it all. I mean, Brian Williams was in Iraq—there was no need to spin the story into a yarn out of For Whom the Bell Tolls.

My second observation is based on my own experience covering emergencies for an international humanitarian agency (Church World Service) and for outlets such as the Century and the National Catholic Reporter. Yes, reporting from Iraq or Afghanistan, Darfur or Haiti, can be alluring and exciting. But the minute some people put on that flak jacket or “humanitarian vest,” as I call it, something happens. It’s like a drug, triggering inflated egos and enveloping the head with the mists and memories of courageous journalists from the past.

It’s a new version of the Lawrence of Arabia syndrome: You start to think you’re the story. “Holy cow, I’m in Iraq,” crows the inner voice of the one-time cub reporter, now middle-aged.

The truth is that such assignments involve long stretches of waiting and boredom. Lots of waiting and lots of boredom—in part because logistics are usually a nightmare. (A ride through Port-au-Prince, anyone?) It’s really not that glamorous, though it is inspiring to see people dealing with the extremes of life so courageously and without complaint.

And there is this. Journalists coming in for small bits of time really are dependent on the efforts, knowledge, and courage of others—minders, drivers, the local staff—for our work. I can’t affirm that enough.

In the end, it’s about getting the story quietly and, in the process, acting modestly and with some humility. It may be easy, at the level Williams works, to forget the modesty factor.

One more thing. Richard Kauffman, a Century editor, reminds me that there is also “a problem with news people embedding with the military, especially when they're thrust into situations where their very lives are dependent on the military itself.” Hard under those circumstances, he notes, for reporters “to maintain distance and offer a critical perspective.”

That’s a different problem, he acknowledges, than the immediate issue of Williams lying or stretching the truth. But Richard is on to something. So are those who say that the real scandal here isn’t about Brian Williams, but about the official lies that led us into a needless war in Iraq. That argument strikes a chord; less convincing to me are theories about faulty memories, or the notion that Williams is a celebrity anchor and therefore not a “real journalist.” In the end, I don’t think any of these should let Williams off the hook. As we learned yesterday, apparently his bosses at NBC agree.

Poor Brian. Now even the veracity of Williams’s post-Katrina reporting in New Orleans is being questioned. David Carr, the New York Times’s fine media critic, said he and others “rolled our eyes at some of the stories Mr. Williams told of the mayhem there.”

All I can say about that is—sure, check it all out. My memory of the Katrina coverage is that Williams did what many of us quieter, non-celebrity journalists try to do after a disaster: talk to the survivors, affirm their humanity, ponder the next step, put what happened into a larger context. He tried exposing the racism and other horrors of a city descending into hell.

But in Iraq? Puffing yourself up as an embedded reporter, dependent on the bravery of others for your story and then “misremembering” what happened? That’s child’s play.