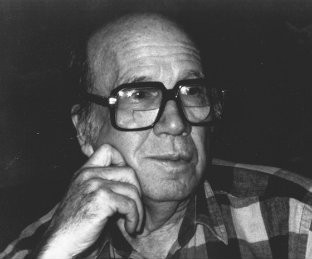

Remembering Will Campbell

As a seminary student in the South in the early 1980s, I found Brother to a Dragonfly—Will Campbell’s moving memoir—as transforming as Barth or Tillich; Stringfellow or Reuther.

There is a section in the book where Campbell, who died this week, realizes in a sort of “second conversion” that Jesus truly died for all people, not just for those on Campbell’s side of an issue. As any pastor knows, it’s tough to minister to folk on both sides. Tough to minister to both the spouse who cheated and the one betrayed. Tough to visit a death-row inmate and also pray with the victims of the crime. Tough to side with the striking coal workers and also listen to the company’s higher-ups within the congregation.

We choose sides. It’s only natural.

Yet Campbell spent time with members of the Ku Klux Klan. He slowly realized that many Klansmen had a history of being oppressed—giving them something in common with the black people they vilified. He reached out to Klan members with the gospel of Christ, all the while maintaining his biblical convictions about equality and justice for all. “Christ was reconciling the world to himself,” Will preached—and all people in that world.

Many of Campbell’s friends in the movement for racial equality were livid that he consorted with “the enemy.” Of course, Jesus got into trouble for eating with the wrong people, too. Campbell got into trouble in lots of different ways during his ministry. But as a seminarian, I was particularly impressed that he dared to take heat for drinking whiskey with the Klan.

“I’d identified with liberal sophistication,” Will said,

and had lost something of the meaning of grace that does include us all. I would continue to be a social activist, but came to understand the nature of tragedy. And one who understands the nature of tragedy can never take sides.

My friend Dot Jackson—a fiction writer and former reporter for the Charlotte Observer—knew Will Campbell. They ate, drank and laughed together when he came through Charlotte. I asked her today about their friendship. Dot responded with this email:

He was soooo funny, so crass, so smart, and so real. He was like a gallstone to a “Christian” community with so little inner heat it would take an undertaker to find it. He appalled them—but there was so much inner fire there and such a tough corps of shameless followers—that kind of like the Pharisees, they didn’t know quite what to do about him. Any complaint from them would have shown up like BS on neon. To those who loved him, Will was kind of our picture of what Jesus must have been like. He was one who seemed to love as Jesus loved, nothing like the pros of the cathedral.

I spent a lot of time in the library as a seminarian. But I learned how to be an effective pastor from a book by a Mississippi Baptist who invited all followers of Jesus to behave as our Lord did, siding with the lost and unlikely, assembling an unusual array of friends. Even if it meant crossing to the other side to drink whiskey with a Klansman.