Compass and yeast

"I believe in . . . the holy catholic church."

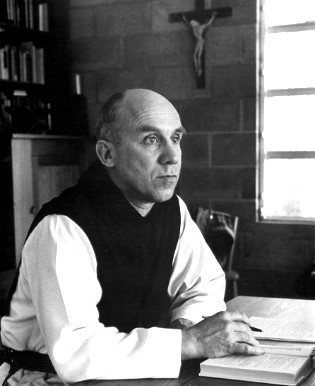

I recently had new reasons to ponder what all "catholic" could mean in the Apostles Creed. I was doing research for a paper and evaluating those of others written for the International Thomas Merton Society conference in Chicago last month. The restless writer's conversion to Catholicism was among the most celebrated of the last century, a point conference-goers took for granted. Trying to make sense of his conversion from the margins, as it were, I asked this: to which Catholicism--to which kind of Catholicism--did Merton convert?

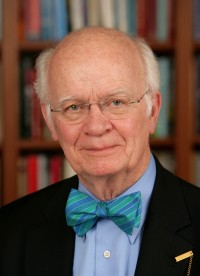

With little time at the conference and even less space here, I chose and choose to pick up on a distinction, or a dual definition, that has stayed with me 60-plus years since I sought and accepted tutelage from Jesuit father Walter J. Ong of St. Louis. Let me pass it on anew.

In numbers of books and articles, including in America (April 7, 1990), Ong presented two images relating to two definitions. Think of "catholic" as a compass and/or as yeast. Ong questioned why the Latin--western, Roman--church borrowed the Greek word katholikos instead of the Latin vernacular universalis, whose meaning more westerners favor. Ong did not disagree with the concept of the "universal" church, but he found it limiting--in part because it intends to limit. Its fuzzy etymology "suggests a compass to make a circle around a central point." It is inclusive because the drawn circle includes everything within it. Fine. But "by the same token it also excluded everything outside" and is subtly negative.

When the hell-raising young convert Thomas Merton turned and saw the gates of the monastery close behind him, he wanted to exclude the world he had known. Thousands of pages of his letters and writings make clear his intention. Yet through the decades--as Merton involved himself in radical social action from within the hermitage at Gethsemani and became "Father Interfaith" in his embrace of Hindus, Buddhists, other kinds of Christians and anyone else spiritually embraceable--he was being "catholic" in Ong's other sense.

Katholikos is "unequivocally positive. It means simply "through-the-whole" or "throughout-the-whole." A bit riskily, Ong ventures that perhaps the Latin entered the Greek church because katholikos "resonated so well" with Jesus' parable in Matthew 13:33: "The reign of God is like yeast," a "limitless, growing reality" that affects everything but does not convert everything into itself. It does not spoil the dough; it makes it more nourishing. The church catholic is to "interpenetrate" cultures not on its own terms but interactively.

That, Ong could argue, is why Merton and his Catholicism(s) led him to interpenetrate cultures of mysticism, poetry, social action, other religions, learning and world affairs. At the Merton conference, these represented interpenetrations showed how after his conversion Merton was Catholic in both senses: of the church both universalis and katholikos. This vision did not let him rest until his last moment, and it's why he still stirs others.