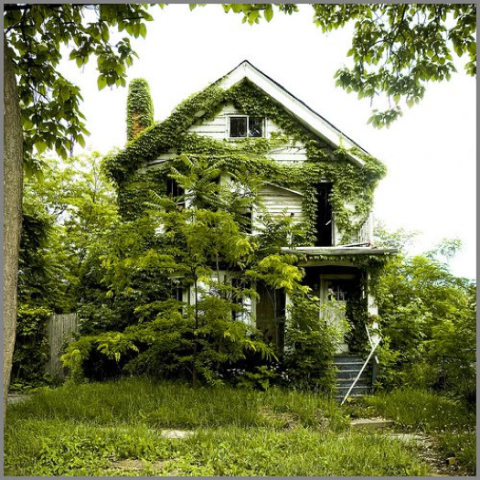

Feral houses in the fallen city

A few weeks ago I traveled to Detroit with

friends who wanted to show us their hometown of Wyandotte, Michigan, just south

of the city. We stayed in a former Navy officers club on Grosse Ile, walked

through Henry Ford's Greenfield Village, then drove in to see a baseball game.

But that's it. That's all we saw. We completely

bypassed the infamous, abandoned tragedy that is Detroit 2010. We thought about

the gutted neighborhoods as we sped past them on the interstate, thought about those

who are pulling scrap out of abandoned buildings for a few bucks, those who are

missing out on an education, those who have no access to a grocery store or

doctor or modern bathroom. We stayed on the freeways and traveled the sports

fans' well-marked path to the stadium.

Even if we had taken a tour of Detroit, where

would we have gone? What would our friends have shown us? Perhaps the most

important admission is that we did not know where not to go, and that many places in Detroit are dangerous.

But Jim Griffioen is not afraid, or if he is, he

overcomes it. Griffioen has become the chronicler of Detroit in demise. He and

his family live in the city, and he regularly visits its gutted neighborhoods or

former neighborhoods with his camera. His photos

of feral houses--his term for the 10,000 or so abandoned homes in Detroit--have

drawn a following. Warning: they are not easy to view, especially all at once.

Adding to the awful silence of these photographs

is the thicket of foliage and trees that is growing around and into many of

these houses--because city mowers (if they show up at all) leave a wide berth,

as if they don't want to get too close. In one photo after another, building

skeletons sit as if collapsing because those who animated them have fled. The

houses are mournful witnesses to a time when there were families here, and lovers,

old people and infants--and tears and laughter and the tedium of daily life. Take

Griffioen's photographs in small doses; too many at one time might convince you

that we're in a national state of emergency re: our cities.

But this isn't all the news from Detroit. Some neighborhoods

have been re-inhabited by artists, chefs and other creative types. Century advertising manager Heidi

Baumgaertner, who pointed me to Griffioen's work, visited friends in one such

neighborhood several years ago. She reports that one couple was living in a

house with a collapsed roof--the first floor was safe and comfortable. They were

content to tolerate the flaw because of the low rent. Other chefs and artists

had settled in, and they often got together for laughter and good food.

There are other bits of good news. The New York Times recently featured

Philip Cooley, a Detroit restaurateur who's made a great success of Slows Bar B Q,

located at the edge of downtown, and is sharing his passion for redevelopment

by becoming a spokesperson and leader for business revitalization.

Then there are the Christian communities that

have stayed in town to serve those who've been left behind in Detroit's great

exodus. In a quick search I found Central

United Methodist, Fort Street

Presbyterian, Genesis Lutheran

(a merger of three churches) and St.

Peter's Episcopal. These and other faith communities are fighting against

the encroaching feral environment of poverty, homelessness, unemployment.

No one expects these efforts to resurrect a city

that's been marked with a big, sad "X" by the entire country. But some hear a

persistent call to leave the freeways, whether to record the urban apocalypse,

make a new home, attempt to staunch some of the despair and hunger, or to be

advocates for those who've been abandoned.