Messy stories: Disabilities and the choices parents make

In the wee hours of a late August morning, I sat exhausted but wide awake beside the bed of my two-and-a-half-year-old daughter. A pink fiberglass cast stretched from Leah’s chest down her entire left leg and partway down the right. The previous afternoon she had broken her left femur. Her thigh bone split in two and nearly end to end when she slipped on a book left lying on the floor.

After a harrowing trip to the emergency room, during which her thigh swelled to twice its size, a team of men in scrubs sedated her and then straightened and wrapped her broken leg.

Leah had broken some bones before—a couple of broken tibias (shinbones) and a broken arm. But I knew from experience that a femur fracture is a different kind of break—more painful and more disabling.

It was dark when we finally got home from the emergency room. After filling her with pizza, narcotics and sedatives, my husband and I settled her down to sleep. But every time she began to relax, the traumatized muscles surrounding her broken bone seized, causing jolts of pain that woke her up. Her pitiful, weary cries chipped away at the remains of my composure. Finally, another dose of sedatives allowed her to drift into oblivion. I was left to ponder what we had gotten ourselves into with this beautiful child.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We brought Leah into the world knowing that she had a 50 percent chance of inheriting my bone disorder, osteogenesis imperfecta, a collagen defect that led me to have three dozen broken bones before my 11th birthday, along with nearly a dozen surgeries and uncounted disappointments and humiliations. We hoped Leah wouldn’t inherit OI but suspected that she had even before the lab test confirmed it when she was six weeks old. Our hearts broke every time she was sidelined with another broken bone, every time circumstances made it starkly clear that our fragile girl could not inhabit the world as safely as her peers could.

As we learned how to be parents to Leah, we were haunted by the question of whether we could take the chance of having another child. That question roared back to life as I sat next to Leah after her femur fractured. Given what we all had gone through, the answer seemed clear: no.

I could not watch another child break bones after insignificant falls and be unable to join in the most routine toddler play because she was too unsteady and fragile. Or rather, I could do it—here I was doing it—but I didn’t want to do it. I wanted a sturdy baby, one who could slip on a book and not end up in the emergency room.

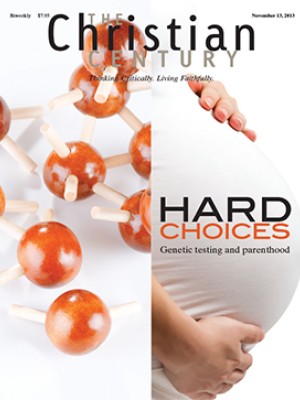

When Leah broke her femur, I was about ready to start a program of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Conceiving our second child via IVF would allow us to undergo preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). All our fertilized eggs would be tested for the mutation that causes OI. If I became pregnant, we would know without a doubt that the baby would not have OI.

As I stroked Leah’s sweaty hair that night, that guarantee seemed more potent and necessary than ever. Preventing OI seemed an obvious good.

But that clarity was short-lived. My theological, ethical, practical and cultural questions about genetic screening and assisted reproduction continued to haunt me, as did questions about the Christian understanding of disability, suffering and what makes for a good life.

In his book Far from the Tree, Andrew Solomon says that stories about genetic conditions tend to reflect one of two primary narratives: either the illness narrative or the identity narrative.

In the illness narrative, disabilities are seen as problems in need of solving, abnormalities that will surely bring great suffering to those affected and their families. In the identity narrative, anomalous conditions such as Down syndrome, autism or deafness are regarded not as flaws but as valuable manifestations of human diversity. The so-called abnormal conditions are disabling primarily because of societal prejudice, ignorance and exclusion, not because of inherent qualities of the conditions themselves.

I find both narratives incomplete, oversimplified and even dangerous when one is embraced to the exclusion of the other. (Solomon also argues that neither narrative tells the whole story.)

Our medical system and our popular culture tend to assume the illness narrative. Cure is the happy ending, and technologies such as PGD that prevent babies with genetic conditions from being born in the first place are the next best thing. The illness narrative says that a baby who is not perfectly healthy is an avoidable tragedy. When I look at our curly-headed girl—talkative, bright, beautiful—I know that the illness narrative is inadequate. To call her life a tragedy is insane.

But it is equally insane to view the challenges of OI as simply one of the many limitations that people face in life. Even if the world were utterly accepting of and accessible to people with OI, the broken bones, surgeries and severe arthritis that afflict people with OI—all of that hurts. A lot. Little girls should not break their femurs just by slipping on a book. These realities are not a challenge to be overcome; they are terrible wounds that cry out for healing, not mere hospitality.

Leah is now nearing 14, and every day with her I have lived with a paradox: I love her just as she is. I love her grace and groundedness. I know that having OI has contributed to her being the wise young woman that she is. And I love my own life. I know that OI has shaped me as a writer, wife, mother and Christian. Yet I still hate how Leah and I have suffered. I long for a cure. If I had a magic wand that could wave OI away, I would use it in heartbeat.

The distinction between illness and identity narratives of disability is useful for understanding cultural debates about disabilities, but neither narrative adequately describes my experience. People’s stories are marked by paradox and complexity. They are messy. We will not have fruitful conversations about disabilities, reproduction, screening and choice until we learn to make such stories the starting point of conversation. We need true and messy stories, not morality tales.

Many people living with disabilities rightly challenge the predominant illness narrative that assumes the inherent goodness of preembryonic and prenatal screening for genetic anomalies. Some people living with genetic conditions see the new genetics as a threat to our very existence—an attempt to annihilate us. Informal rules have cropped up concerning which stories are and are not welcomed into the conversation.

Amy Julia Becker, who writes frequently about having a daughter with Down syndrome, found this out last year when she published a series of stories on her Patheos blog about people’s experiences with prenatal diagnosis. She included the story of a woman who chose to abort a fetus diagnosed with Down syndrome. Becker told me that she received private correspondence from advocates for people with Down syndrome who said her decision to post the story undercut her primary goal of encouraging grace-filled hospitality for people with Down syndrome. Yet 75 to 80 percent of women who receive a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome choose termination. So the most common story is, in the eyes of some advocates on this issue, the very story that should not be told.

Becker also notes that she and other parents of children with Down syndrome hesitate to talk about the hard moments they have with their children. To admit that they sometimes struggle to parent a child with Down syndrome and worry about the child’s future can feel like a betrayal, a form of caving in to the narrative that says children with Down syndrome live tragic lives and that everyone would therefore be better off if such children were not born.

Becker notes that she doesn’t hesitate to talk about the hard moments in parenting her son who does not have Down syndrome. She doesn’t worry that someone hearing that story will say, “See? Little boys are so difficult. People should terminate pregnancies with little boys so they won’t have to deal with all this hard stuff.”

A friend who has a daughter with Down syndrome frequently shares with community groups her recollection of the day her daughter was born. She describes how she sat in her hospital room thinking, “I don’t want this baby. I don’t know how to handle this baby.” The mother of a child with Down syndrome scolded her for telling this story instead of focusing on the positive aspects of raising her child.

People’s stories are full of paradox and contradiction, and people are too often silenced or ostracized for fear their stories will provide fodder for the “opposing side” in the debates over disability, illness, suffering and the promises and pitfalls of medical, reproductive and genetic technologies.

The preference for simplistic narratives is apparent in our tendency to cast stories as morality tales. In an online post for the journal First Things, Philip C. Burcham told a compelling story of his family’s history with OI in which he referred to a doctor as a “eugenicist.” The doctor had assumed that Burcham and his wife, whose first child inherited OI from Burcham, would want to do everything in their power to avoid having “another one of those.”

The doctor’s unquestioned acceptance of the prevailing illness narrative, in which the sole desirable goal of any pregnancy is the birth of a child without any genetic abnormalities, deserved Burcham’s criticism. But there is no evidence that the doctor was guilty of eugenics, which is a philosophy and sociopolitical movement that supports selective breeding for the “improvement” of the human race. By labeling this physician a eugenicist (a term associated with horrific policies in Nazi Germany and elsewhere), Burcham moves from telling his family’s story to preaching a morality tale. The misguided doctor becomes a villain, rather than a flawed human being who thought he was doing the right thing even if he wasn’t.

The temptation to reduce complex human stories to simple morality tales has emerged in people’s responses to my own story. My husband and I ultimately abandoned PGD and had another baby naturally. When people learn this fact, they want to transform our story into a shiny morality tale in which we “saw the light” and the error of our eugenic ways and left PGD behind for the more loving decision to accept whatever naturally conceived child we got.

Our choice wasn’t that simple, though. Such choices rarely are. A few days after Leah fractured her femur, we started an IVF cycle, with its attendant injections, ultrasounds, blood tests, stress and expense. Of four fertilized eggs, only one tested negative for OI. That fertilized egg was put back into my uterus, but a pregnancy test two weeks later was negative. We planned to try again.

Then we got distracted by Leah getting her cast off and starting preschool, by buying a new house and by wondering where we’d get the money for another cycle of IVF. We continued to ask ourselves questions about what makes for a fulfilling life, parents’ duties to children and how today’s overwrought parenting culture skews and distorts those duties. Those questions haunted me—but they didn’t quite convince me to pick up the phone to tell the fertility clinic that we were done with PGD and IVF.

Pondering those questions did, however, make it easier to embrace, with gratitude and some trepidation, the pregnancy that occurred naturally before we got a chance to return to the clinic.

Yes, we abandoned PGD and went on to have two more children conceived naturally, neither of whom inherited OI. But it was not because we clearly saw the light about anything.

Christian scriptures are a treasure trove of messy, complicated human stories. We should know better than to cheapen our own stories by recasting them as morality tales, with radiant shafts of light revealing good and bad, right and wrong, hero and villain.

In the Bible, the heroes are flawed and the good guys don’t always win. Even stories in which there is a clear message for how to live in the world and with each other are full of complexities and contradictions.

We rejoice at the father’s ecstatic embrace of the Prodigal Son—and we feel a little miffed on behalf of the responsible other son. We are in awe of the creator God’s rebuke of Job—and we think that Job had good reason to complain to God (and suspect we would do the same thing). We understand why Jesus said that Mary was doing the better thing—and we wish she and Jesus had just gotten up and helped Martha with the meal. Our scripture also reminds us that we see as in a mirror, dimly. Any story that fails to acknowledge that dimness, that murkiness, is a story I have difficulty trusting.

True stories, like biblical stories, are multifaceted. This complexity is inherent in a narrative approach and is what makes the narrative approach so useful. Although naming and accepting the tensions, messiness and complexity of stories is difficult, this type of storytelling leads to compassion, wisdom and ultimately conversion—the choice to risk a new way of seeing the world, ourselves and others and new ways of living in the world and with each other. Stories help us seek a better way while understanding that there is rarely anything so clear as the best way.

Stories honestly told, with all their murkiness intact, point the listener and the storyteller to something larger than themselves. Research shows that children who hear and retell strong family narratives—who know their families’ stories—are more resilient because they know they belong to something larger than themselves. When we tell and listen to difficult, multifaceted stories, it becomes harder and harder to make black-and-white declarations of what is right and wrong. This lack of clarity in turn forces us to look outside of ourselves for guidance—to scripture, to our communities, to our traditions, to the wisdom of others who have grappled with similar questions.

Thus, contrary to the popular notion that narrative (story-focused) ethics promotes relativism, whereby every person seeks his or her own truth based on his or her circumstances, this process actually leads us to seek wisdom from outside of our limited vision. Venturing into the messy landscape of story provides a lesson in humility, reminding us that we have much to learn from both our own stories and the stories of others.

If a primary goal of advocacy for those with disabilities is to insist that society see us as fully human, let’s start by allowing people to tell true stories that bear the marks of that humanity—tension, paradox, regret, pain and grief as well as joy, success, happiness, love and accomplishment.

When I talk about our decisions in regard to using reproductive technology, I still don’t know whether the decisions we made were right or wrong. I do know, however, that I need to keep telling my story and inviting others to tell theirs.