Hidden in Timbuktu: An Islamic legacy protected from jihadists

After a brutal ten-month occupation of Timbuktu, jihadists fled that city in Mali in February of this year—but not before burning all the ancient manuscripts they could find. The city’s Muslim residents have carefully guarded the old documents for centuries. These manuscripts portray an Islam that is largely curious, tolerant and interested in engaging the world, which is why the jihadists were eager to destroy them—and why residents were so eager to hide them when they got news of the impending invasion.

Located at the edge of the Sahara Desert, Timbuktu became a regional hub for the trade of salt, gold and slaves in the 13th century, as well as a center for Muslim scholarship. Intellectual inquiry often suffered at the whims of military commanders, and the city was captured and recaptured by regional kingdoms and tribal militias that were suspicious of those who sought wisdom rather than power. This was the fate of Ahmed Baba, a 16th-century scholar who wrote more than 40 books but was exiled from Timbuktu after the city was captured by a Moroccan army.

Located at the edge of the Sahara Desert, Timbuktu became a regional hub for the trade of salt, gold and slaves in the 13th century, as well as a center for Muslim scholarship. Intellectual inquiry often suffered at the whims of military commanders, and the city was captured and recaptured by regional kingdoms and tribal militias that were suspicious of those who sought wisdom rather than power. This was the fate of Ahmed Baba, a 16th-century scholar who wrote more than 40 books but was exiled from Timbuktu after the city was captured by a Moroccan army.

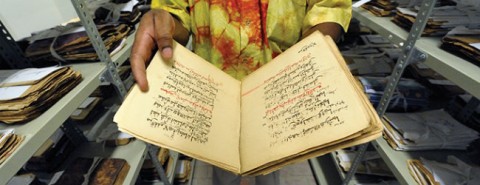

In the center of the city is a library named for the scholar. The architecture of the Ahmed Baba Institute uses natural air currents to keep people cool inside despite the desert heat outside. State-of-the-art labs preserve ancient manuscripts collected from throughout West Africa. Interim director Abdoulaye Cissé walked me through the document-preservation labs, where anything that the jihadists found was looted or destroyed. Then he led me down to the basement and through a dark hallway, fumbling around until he was able to unlock a door and flip on a light switch. Dozens of piles of manuscripts were carefully stacked on shelves.