I was sitting at the counter in a neighborhood restaurant, eating breakfast and chatting with my server, who also happened to be a friend of mine. She recounted a conversation she had after church the previous Sunday. The woman she talked to was not happy with the preacher that week or with his sermon. She complained to my friend, “The sermon didn’t make me feel good.” My friend replied, “Jesus didn’t come to make you feel good!”

Indeed. Although he certainly did make some people feel good. I would expect that the people Jesus healed felt good. The hungry people he fed felt good. The people whose demons Jesus exorcised felt good. The people who were sinners and yet included at Jesus’ table probably felt good.

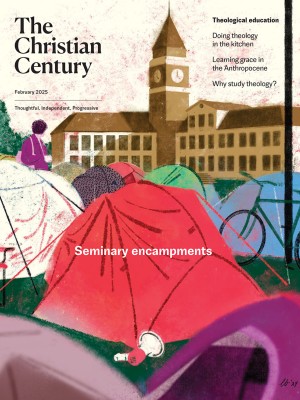

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But the people of Nazareth at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry? They definitely did not feel good. Jesus did not come to make them feel good.

But what did he come to do? In one way, the question is easy to answer. Jesus answers it in the scripture he quotes in this story. He came to bring good news to the poor, to set the captives free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. He came to fulfill the prophet’s words, which is music to the ears of the people in Nazareth. Because they think when Jesus says “the poor” and “the oppressed” that he means them. Why wouldn’t they? And that would make them feel good; in fact, good is probably too small of a word.

What did Jesus come to do? There are so many ways to answer this question, actually. I remember Jaroslav Pelikan’s classic book Jesus Through the Centuries, on the cultural history of images of Jesus. From rabbi to cosmic Christ, how have we imagined what Jesus came to do? I don’t remember most of the images from Pelikan’s essays. Just that you can hold Jesus up to the light and see many different things. Friend of sinners. Christus victor. Advocate for the poor. Disrupter of social systems. Personal savior.

There is something both hopeful and unsettling for me in this story from Luke. As a Lutheran pastor, I have always been taught to gravitate toward the “for-you-ness” of the gospel. When I serve communion, I always put the bread in open hands and say the words, “Given for you.” I believe that these words hold the power to set people free. But the scene in this story challenges some part of this notion. The message Jesus brings is not simply “for you”—and that causes rage in the people of Jesus’ hometown. They came to hear words that they assumed were for them.

Jesus tells them truths they do not want to hear. He doesn’t put the bread into their hands—at least not on this particular day. He suggests to them that there are others who are oppressed and who need to be freed, that there are others who are hungry who need to be fed. He even tells them that there are others who are faithful but are not even in their field of vision.

Robert Jones’s book White Too Long is about the complicity of the American church with White supremacy throughout our history. Reading it, among the many things I learned was this: that the emphasis on sin and personal salvation in Jones’s Southern Baptist church was a powerful anesthetic for White supremacy and racial injustice. Salvation was all about people’s personal relationship with Jesus, not the social injustices just outside their doors. Somehow the for-you-ness of the gospel got in the way of the truth.

Does it still? Sometimes I think so. In my heart, I want to believe that the good news of Jesus’ death and resurrection will turn us not just to God but to our neighbor, that when the bread is put in our hands we will want to turn around and share it with others, not keep it to ourselves. I want to believe that experiencing the love of Jesus sets us free to love others. I want to believe it and do believe it.

But my friend was right. Jesus didn’t come to make me feel good. Jesus didn’t come just for me. The for-you-ness of the gospel extends far beyond my comfort zone. And part of what it means to be saved is to have that comfort zone stretched until your heart aches for others.

Jesus didn’t come to make us feel good. He came to set us free, whether it feels good or not.