April 17, Maundy Thursday (John 13:1-17, 31b-35)

We need to find a way to wash each other’s feet, even when waging war feels better.

Three years ago, the Lawrence Journal-World ran a story about a young woman who fell into the Wakarusa River while visiting the Baker Wetlands in Lawrence, Kansas. The swift current carried her five miles downstream. She described making several attempts to fight the current, to no avail—and then realizing that she would die if she continued. She decided to allow her body to go limp, and she believes that choice is what ended up saving her life.

The story of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet on the final night of his life offers another kind of glimpse into what it means to allow softness to guide us.

John 13 brings both the close of Jesus’ earthly ministry and the beginning of his final night with his disciples. For the next several chapters, Jesus spends that final night before his arrest preparing his disciples for his death and for what life will be like without him. John’s is the only gospel in which Jesus does not break bread with his disciples to institute the Last Supper that final night but washes their feet instead.

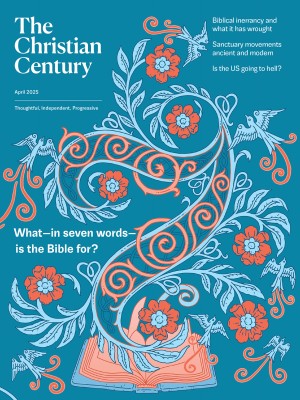

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Foot washing was customary in both Greco-Roman and Jewish contexts, but the way Jesus does it subverts those customs. First, it typically occurred as guests arrived, not in the middle of a meal. Second, foot washing was not meant to attract attention, yet Jesus makes it the main event of the evening. Finally, the servant or person of lower status would be the one to wash the feet of the higher-status guest, never the master washing the feet of the servant.

When Jesus wraps himself with a towel to prepare to wash his disciples’ feet, he adopts the attire and position of a servant. The foot washing itself also subverts the disciples’ expectations and common convention, given that it requires Jesus to assume a position of lesser status. Furthermore, Jesus washes the feet of Judas, the man he knows will betray him, and Peter, the man he knows will deny him once he faces trial.

Perhaps most scandalous of all is that Jesus closes the foot washing ritual with the instruction that the disciples should treat one another this way, that this is the love they ought to show each other and the world. Jesus knows he is about to face arrest, trial, crucifixion, and death, yet he chooses to spend his final night showing the disciples what it means to lead and what it means to love.

Contemporary readers may take this story for granted, given how many times they have heard it and the way it can be used to overspiritualize Jesus’ mission. But readers attuned to the way Jesus’ actions in this passage would have landed for those present—and for those who would have first heard the story—understand the gravity of foot washing as a revolutionary act and the way it aligns with everything Jesus has told people about himself.

In an age of rulers who rule with brute strength, oppression, and violence, Jesus demonstrates that he came to rule with service, liberation, and love. In washing the feet of his disciples—including those who will fail to stand beside him in his trial and death—Jesus redefines what it means to be a master, a ruler, and a leader. To say that Jesus is Lord is to say that Caesar is not.

The meaning of Jesus’ actions on his final night bears relevance for 21st-century Christians, as we too face institutions and structures that claim divinely ordained power and authority but ultimately fail to live up to their promises, instead pursuing policies and actions that lead to exclusion, violence, injustice, and oppression. At a time when success in leadership is defined by the promise of prosperity, military power, and the will to vanquish enemies of the state no matter the cost, the contemporary world could use an example of what it means to lead with softness and love. At a time when strength in leadership is characterized by sending millions of dollars in weaponry to aid in an unjust war against the Palestinian people, we are in need of the kind of power that seems weaker and softer on the surface, that tells stories of Palestinian joy, resilience, and love, that insists on a lasting ceasefire.

Jesus’ message to us is that strength is in softness, leadership is in service to one another—especially those who are oppressed—and power is in love. We need to find a way to wash each other’s feet, even when waging war is what feels better.