The imitation of the Spirit

Christians are taught to practice imitatio Christi, empowered by the Holy Spirit. What if we flipped this narrative?

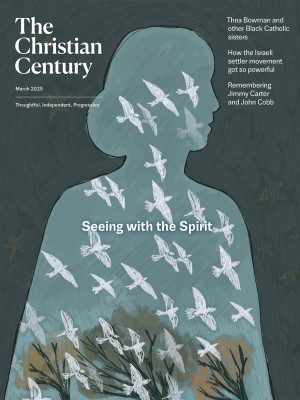

Illustration by Martha Park

Traditional language about Christian spiritual formation has long been shaped by the impulse to imitate Jesus, a call we hear ringing in Paul’s exhortation to “be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). Thomas Aquinas describes this process as “manuduction”: Christ guides or “leads by the hand” his siblings to union with his Father, both making it possible and showing us the way. Christians have framed this activity of growing in Christlikeness in quite a variety of ways—through self-sacrifice or taking up a life of poverty and simplicity, through a focus on interiority and prayer, through committing to acts of radical justice and the breaking of social barriers. Common to all these variations in spiritual formation is the believer being conformed to Christ, a transformation enabled by the Holy Spirit through divine grace. We imitate Christ; we are empowered to do so by the Holy Spirit.

I would like to suggest, as a thought experiment or spiritual exercise, flipping that narrative. What insights might emerge about the life of faith if we took the Spirit’s way of moving among and with us as the model to imitate? What if we imitated the Spirit, empowered by the redemptive love of Christ?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Certainly, Christ through his incarnation became God with us, Immanuel, the center point of redemption history—and therefore following and being united to Christ is rightfully spoken of as the shape of the believer’s life. However, there is also a special way in which the Holy Spirit is present to us and with us in our own world and our time. When we ask how we might imitate the Spirit, the central question of spiritual formation becomes this: What can I learn about graced, charity-informed interactions with and among the people around me by considering how the Holy Spirit acts toward us? In this framing, counterintuitive as it may be, the Holy Spirit becomes a model for the concrete activities of human living animated by the love of Christ.

While tradition rightly advises against making too stark a distinction between what scripture means by “the spirit of Christ” and by “the Holy Spirit,” we can nevertheless clearly see Christ speaking to his disciples of the coming of the Holy Spirit as a distinct person, whose mission is to make present to the believer the divine gifts and to assist them in making use of these gifts in the contexts and interactions of human life. While we address our prayers to God and to Christ, it is the Holy Spirit who is in the room with us, who is attentive to current events in our world, who is present when we talk to our neighbor, and who is intimately acquainted with how we act at work and at home.

In his introduction of the Spirit to his disciples in John 16, Christ identifies the Spirit’s role as guiding believers into all truth. This truth has been shared by the Father with the Son, then the Son with the Spirit, and then the Spirit with us. This experience of shared truth merits a closer look, as it seems central to the shape and goal of spiritual formation. In human terms, the experience can be described as one person saying, “Look at this!” to another.

This is a special kind of shared activity that developmental psychologists refer to as “joint attention.” Theologian Andrew Pinsent discusses this phenomenon, and its potential to help us think about spiritual formation, in The Second-Person Perspective in Aquinas’s Ethics. Joint attention is not just two people giving attention to the same thing. Rather, it includes a complex mutual awareness: one person draws the attention of another person to some object for consideration by them both. It seems simple when experienced, but it is indeed a sophisticated relational event, reliant on the extraordinary power of the second-person pronoun.

You is quite a marvelous word. For it to work in a meaningful way in conversation there must be at least two I’s, two individuals who understand themselves each to be a subject in their own right and the main actor in their own narrative. I indicates self-aware agency. But this is just the foundation, the raw materials for a second-person exchange. If one person sees another person busy with their own thing, such that the second does not see them back, there are indeed two I’s but not yet a you. If the first person looks away, and the second looks up and sees them, it is still not a you. Even if one person talks at another and the other hears, it’s not necessarily a true you moment.

A true second-person relation requires mutuality—one person’s acknowledgment of the other person being aware of the interaction and vice versa. I see you seeing me seeing you. It sounds a bit circuitous, but that’s what you means in its fullest sense: it implies a closing of the circle of personal and interpersonal awareness.

As Pinsent envisions it, the phenomenon of joint attention occurs when two people are not only aware of themselves and of each other but then go on to have a shared experience of attention to some other thing. At its most basic, this means one person getting another’s attention and then directing that attention toward something else. This is more, however, than just two people having seen the same thing. The presence of one person actually shapes the other’s experience of that thing. Their view of it, their understanding of it as truth, matters. This is sometimes also called a “shared stance.”

The truly remarkable thing about joint attention is how the activity relies upon, and therefore affirms, the self-aware agency of both participants. A meaningful use of the word you—in contrast to the impersonal tone that can characterize a careless “Hey, you!”—is perhaps among the most intimate of interpersonal moments.

In Aquinas’s thought, these notions—joint attention, shared stance, personal agency, and the second-person notion of you—come together in his treatment of the Holy Spirit. We see this in the Summa Theologiae in the language he uses to describe how the gifts of the Spirit dispose a person to be moved by God. The paradigmatic divine gift, for Aquinas, is the theological virtue of charity, the receiving of which makes human beings friends of God. This impartation of divine love, he tells us, is the primary role and work of the Holy Spirit, and indeed is the reason why Gift and Love (especially when understood as “love proceeding”) are fitting names for the Holy Spirit. They indicate not only the Spirit’s nature but also its operation among human beings. Aquinas reminds us that a gift is something that, once given by another, belongs to the recipient, to enjoy and to use as they wish. Even divine love is given to us in the true sense, in that we are able to truly possess it and put it into action using our human ways of knowing and loving.

How does this gifting actually happen, and what does this tell us about how the Holy Spirit works? When informed by charity we are made able, as theologian Thomas Ryan describes it, “to know, feel, love, and act as God does.” That is, using Pinsent’s language, charity enables us to have a shared stance with the Holy Spirit toward people and things in our world (and, preeminently, toward God).

Such a graced stance does not, however, merely mean that our eyes and heart are pointed here and there by the Holy Spirit as if we are sock puppets. Rather, the fact that we have become friends of God means that the Holy Spirit desires to view the world with us, not just for us. Knowing, loving, and responding to the world with divine charity is a shared activity, an act of joint attention between us and the Holy Spirit, a second-person relation of mutual love for each other and the world. What a generous stance the Spirit has toward us, to treat each of us as a genuine you—to be not only willing but eager for the divine and human narratives to be thus intermingled, to let human thoughts and actions make their marks on the divine story of redemption.

We can imagine the Holy Spirit’s loving, friendly invitation to participate: “Well, what do you think about that? What do you think we should do?” In Aquinas’s vision of the Holy Spirit’s role in the life of faith, it matters that we contribute actively (even, or perhaps especially, in all our flawed humanity) to the Spirit’s great mission of making divine charity present and at work in the earth.

We are now ready to ask: What might it look like not only to benefit from the Spirit’s collaborative, second-person way of moving among human beings but also to be formed by it and to imitate it ourselves? What might our own ways of doing life together look like if we appropriate the Spirit’s grace-filled ways, if we too become gift and love to those around us?

First, let us consider the notion of regarding another person as a true you—a relation experienced by stopping and opening ourselves to another as a complete person in their own right, as a truth teller of their own narrative, and as having a perspective on the world that reflects their own personal agency. A second-person orientation toward another person affirms all this.

This may be an uncomfortable and even a risky undertaking. A genuine shared-stance version of questions such as “What do you think about that?” includes a willingness on the part of the asker to be led to look at something from a certain perspective. It entails allowing another person temporarily into the driver’s seat of my own engagement with the world. It is still my act of knowing, and I can always decide I don’t quite agree with the other’s conclusions. But my experience of the thing will now always be marked by, even contain ideas from, having been seen in a shared stance with the other person. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum, reflecting on such complex moments of human solidarity in Love’s Knowledge, beautifully observes that “fellow-feeling” of this kind is what holds the world of human experience together.

Second-person relations entail, therefore, a tremendous vulnerability. We are marked by those we share a stance with. My life, and my own narrative, when interwoven with moments of openhearted joint attention, will not be as they would have been if I had just stayed with my own loved ones or with people pretty much like me. But if a person is willing to pay that price, they set great things in motion. They give one of the finest gifts a person can give to another: their genuine, active attention. It is remarkable the effect such an act of giving has on another person’s agency. Treating someone as a meaningful you affirms their own sense of I and gives them a relational space in which to express that identity. Asking “What is it you wish to show me?” affirms that the other person, as the subject of their own story, has thoughts and experiences that make them a relevant truth teller about the world.

It is also remarkable, however, how very hard it is to do this seemingly simple thing. Despite our declarations of valuing empathy, humility, and even just open discourse, the you questions may stick in our throat. Why should I be generous and openhearted to them, when they aren’t that way toward me?

Now we have arrived at the crux of the matter. Christians, according to our most cherished beliefs, should be the most ready and willing to embrace this openness and generosity of spirit. We have the example and the help of the Holy Spirit to do this very thing that is so central to human experience. If the Holy Spirit is so generously willing to interweave in messy human affairs, then we need not fear the risk of sharing a stance for a time, even with someone whose perspective we suspect will leave an uncomfortable mark upon our lives. We should recall that the Holy Spirit’s outpouring of divine charity within us really does enable our own human minds and wills to do what feels superhuman: to affirm the agency of someone we don’t trust, to give our attention to someone we feel does not deserve it, to look at the world through the eyes of someone with whom we feel no values in common. To link our sense of self with such another’s in a mutually referential, second-person, shared stance toward the world.

The question thus becomes, “Are we willing to do such a thing?” With the help of the Holy Spirit, will we open ourselves in the act of hospitality that is captured in the word you—making room for another being in one’s soul and accepting their offer to do the same?

One final element from Aquinas’s account of the Holy Spirit emphasizes just how much the Spirit helps us to act in this generous, openhearted way. In his discussion on the fruits of the Spirit, he identifies one particularly interesting effect of the Spirit within the believer: benignity (in Aquinas’s Latin: benignitas). In common language we might describe this fruit as gentleness, or kindness. Aquinas, however, uses wordplay to illuminate the nature of this divine fruit. The word benignity, he notes in his commentary on Galatians 5, indicates a “good fire” (bona igneitas), one that “makes a man melt to relieve the needs of others.” The benign person is one whose heart and mind are softened toward another, melting away hardness and rendering the person open, patient, receptive. We see this same theme appear in his treatment of love in the Summa Theologiae, where he says that “the freezing or hardening of the heart is a disposition incompatible with love: while melting denotes a softening of the heart, whereby the heart shows itself to be ready for the entrance of the beloved.”

What a beautiful image Aquinas leaves us with: the Holy Spirit disposes us, through the divine gift of charity, to be softened in our hearts toward other people in our world, open and ready to receive them into ourselves as beloved. The Spirit models this for us as well, as divine Love proceeding into our world of human affairs and concerns, a self-opening of the heart of God toward the messy, fraught human community, calling to and receiving each as a beloved you.

In our ongoing practices of Christian spiritual formation, we are rightly encouraged to continue in the long tradition of imitating Christ, following him as the “firstborn within a large family” (Rom. 8:29). We might also, however, be inspired to add to our understanding of just what that might mean by taking a close look at how the Holy Spirit moves among us and with us in our daily lives.