Early Christianity, fragment by fragment

A new published volume of ancient papyri contains sayings, attributed to Jesus, that were previously unknown—including a dialogue with a disciple named Mary.

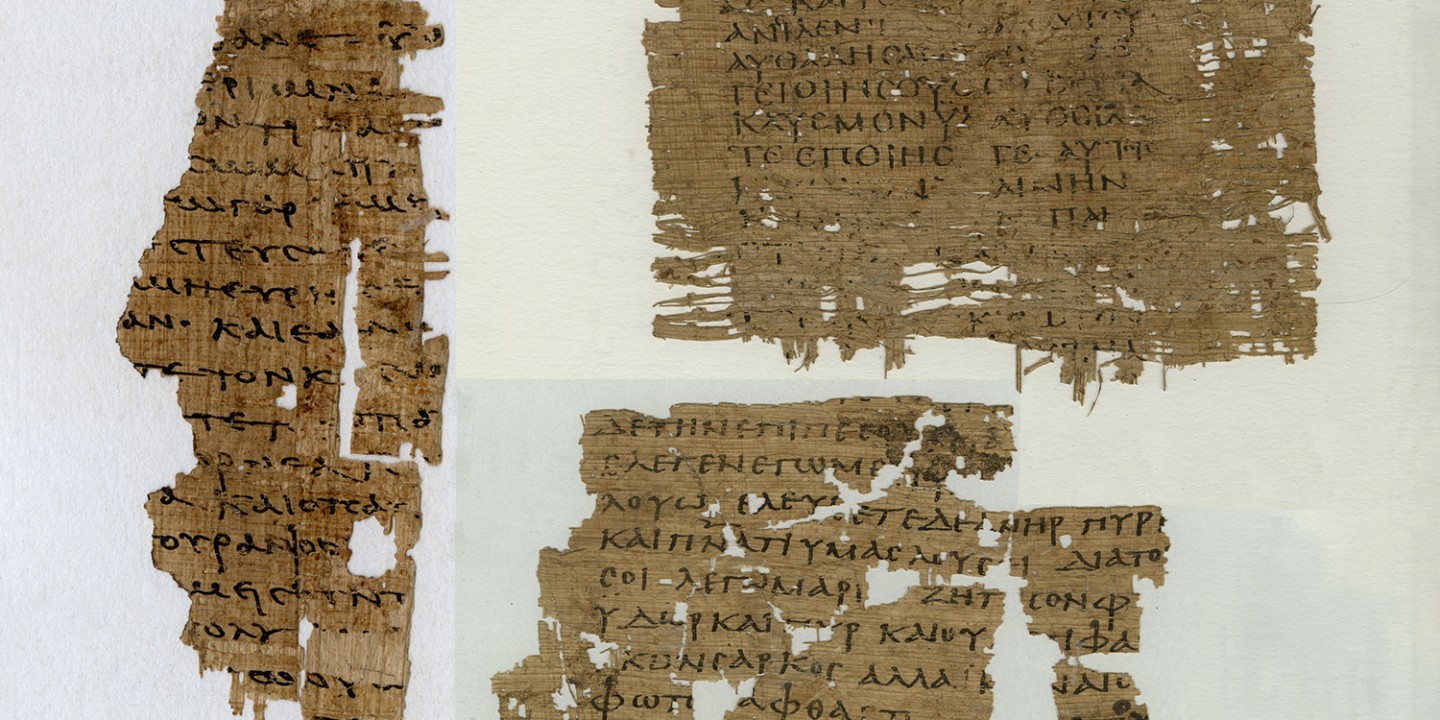

Last summer brought big news for scholars of early Christianity. Three previously unknown gospel fragments were published for the first time as part of an ongoing series, The Oxyrhynchus Papyri. These three Greek manuscript fragments, which scholars date between the second to the fourth centuries CE, all purport to preserve otherwise unknown sayings of Jesus.

They were copied on papyrus, the most common writing medium used in ancient Egypt. Although the papyri have similarities with more familiar gospels, these particular ancient Christian texts were previously unknown to scholars. They have been cataloged as P.Oxy 5575 (“Sayings of Jesus”), P.Oxy 5576 (“Gnostic Text”), and P.Oxy 5577 (“Valentinian Text?”).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In the late 1890s, two Oxford professors named Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt began excavations in Egypt in search of ancient papyri. By some accounts, their goal was to rescue papyri from ancient rubbish mounds before farmers dug the mounds up for fertilizer. But Grenfell and Hunt were also rather opportunistic in their timing: this was during the British occupation of Egypt (1882–1956), when British excavators could legally claim whatever Egyptian antiquities they discovered and bring them back to England.

In 1896, Grenfell and Hunt began digging in the ancient Christian city of Oxyrhynchus (today Al-Bahnasa) with a large team of local workers. They soon struck gold. The rubbish heaps contained hundreds of thousands of papyrus fragments, representing a huge range of written material: receipts, letters, fragments of the gospels, portions of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and many unknown literary works. These texts were mostly copied in Greek, and they dated from the second century BCE to the seventh century CE. Although the papyri were falling apart, many were still legible due to having been preserved in Egypt’s dry climate. The website for the Oxyrhynchus papyri explains that ever since Grenfell and Hunt’s excavations, “scholars have worked continuously to catalogue, decipher, and publish this material” in the now 87 volumes of the series. (To learn more about previously published Christian papyri from Oxyrhynchus, see AnneMarie Luijendijk’s Greetings in the Lord or Lincoln Blumell and Thomas Wayment’s Christian Oxyrhynchus.)

Grenfell and Hunt brought back an astounding half a million papyrus fragments to Oxford. More substantial papyri comprised a few pages, but most were smaller than a business card. Today the papyri are housed at Oxford’s Bodleian Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library (formerly the Sackler Library). They are a treasure trove of information about the ancient world, including early Christianity.

To some extent, the Oxyrhynchus papyri were overshadowed by the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945. When people think about lost Christian gospels, they often have in mind these codices, which were copied in Coptic in the fourth or fifth century. The Oxyrhynchus papyri are much more varied and fragmentary than the Nag Hammadi library, but they still have much to tell us about Christian origins, particularly in Egypt in the first centuries of the Common Era.

In fact, the very first volume published by Grenfell and Hunt in 1897 contained a text called Logia Iesou: Sayings of Our Lord from an Early Greek Papyrus. Although they didn’t know it at the time, P.Oxy 1 preserved the opening of the lost Gospel of Thomas, which would be discovered in full at Nag Hammadi. Other notable “lost gospel” fragments would also eventually be published in the series—including a potential section of the Gospel of Peter (P.Oxy 2949) in 1972, a section of the Gospel of Mary (P.Oxy 3525) in 1983, and a possible rewriting of Mark 5 or Matthew 10 (P.Oxy 5072) in 2011.

Today there is approximately one volume published in the Oxyrhynchus Papyri series each year, and more than 5,600 papyri have been edited. Considering the time and effort it takes to decipher and edit each scrap of papyrus, it is daunting to consider that hundreds of thousands of scraps still remain unidentified and unpublished. The series has its work cut out for many years to come, and many more treasures may yet come to light.

The 2023 volume presents “first editions” of 58 papyri discovered more than a century ago at Oxyrhynchus. Most of these texts are banal snapshots of ancient Egyptian life: “Order to Pay Rent,” “Receipt for the Price of Cogwheels,” “Receipt for Wine,” “Account of Sale of Acacia Wood.” This volume also includes a section of Paul’s letter to the Romans, a fragment of Revelation 17, and some classical texts. But Christian readers will be most interested to learn about the three previously unknown gospel fragments that purport to preserve words of Jesus.

My own research focuses on Mary Magdalene, so I will start with a discussion of a fascinating papyrus that preserves a dialogue between Jesus and a disciple named Mary. The editor of the papyrus, Juan Chapa of the University of Navarra, dates this manuscript to the fourth century (although the dating of ancient manuscripts is rarely certain, and in any case the dialogue itself could have been authored much earlier). Here is Chapa’s reconstruction and translation of the fragment:

. . . good Father . . . introduces (?) the simple and incorruptible form. Therefore I say, Mary: I showed myself as the artificer mind in the logos made flesh filled with the incorruptible Father, awakening through my kindness the hidden life of the Father . . . form and . . .

. . . will fall on the earth. [John] said: “I bathe you with water, but a man will come and will bathe you with fire and spirit.” Therefore I say to you, Mary: seek to mix water and fire and you will no longer appear as an image of flesh, but an image of the eternal incorruptible light, bringing together for you, Mary, intellectual spirits from two intertwined and dissolved elements.

What does this fragment tell us? First of all, it appears that a disciple named Mary is being given a special revelation. The person speaking to Mary refers to himself as the logos (word) made flesh, and Chapa concludes that this “strongly suggest[s] that the speaker is Jesus.” As far as we can tell, Mary is the only person that Jesus is speaking to. After he refers to the baptism of John, who only bathed with water, and his own baptism with “fire and spirit,” he instructs Mary to “mix water and fire” in order to advance spiritually. He says that she will then no longer appear as a fleshly image but as an image of “eternal incorruptible light.”

What does this mean? Since the papyrus is so fragmentary, it’s difficult to be certain, but the references to water and fire are likely symbolic. This focus on Mary, as well as the emphasis on water, fire, light, and baptism, are similar to the Gospel of Philip, which was found at Nag Hammadi. That gospel is thought to be associated with the second-century teacher Valentinus; in part, this is why Chapa has titled the fragment “Valentinian Text?” Yet even this possibility is uncertain, since there were many early Christian groups interested in baptism, initiation, and symbolism around fire and water.

When Chapa unveiled this fragment at a conference in Vienna last July, German scholar Silke Petersen asked whether P.Oxy 5577 could be part of the missing section of the Gospel of Mary. This gospel was probably authored in the second century by a community that revered Mary Magdalene and is preserved in the fifth-century Berlin Codex (another important “lost gospel” manuscript written in Coptic) and two other third-century Greek fragments discovered at Oxyrhynchus. The Gospel of Mary describes a woman named Mary encouraging other disciples after Jesus’ departure; she then shares her own vision of a conversation she had with “the Savior.” Unfortunately, in the section where Mary describes this vision, several pages are missing from the Berlin Codex, and neither of the two Greek fragments preserves this lost content.

Has a missing section of the Gospel of Mary finally come to light? At the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting last fall, British specialist Sarah Parkhouse built an argument that P.Oxy 5577 may indeed retain a portion of that gospel’s missing vision section. Parkhouse even asked for a show of hands to see which of the 70 or so scholars in the room were convinced that this might be the Gospel of Mary, and more than two-thirds did so (including me). While it can’t be proven, it is a reasonable possibility.

But caution is also in order. When I asked Mark Goodacre of Duke University whether he thought P.Oxy 5577 was a piece of the Gospel of Mary, he said to me: “The thing that makes me cautious is that it has the Matthean-sounding ‘Therefore I say to you’ twice, and for such a tiny fragment that is striking, since the expression does not come anywhere else in what we have of the Gospel of Mary. Also, we have ‘incorruptible light’ and ‘incorruptible Father’ in the fragment, as well as a second ‘Father,’ but we don’t have any of that vocabulary in what we have of the Gospel of Mary. These are not decisive points, especially when dealing with such a small fragment, but they are enough to make me pause.”

Goodacre is correct that if P.Oxy 5577 is part of the Gospel of Mary, it would turn many assumptions about this gospel on their head. It may be that we simply didn’t have access to the sections of this gospel that refer to God as Father, and it could also be that Mary’s vision is stylistically different than the rest of this gospel. It’s a shame that we do not have more of the papyrus preserved, since there was certainly additional content; many have longed to know what took place in Mary’s missing vision.

But even if this is not a portion of the Gospel of Mary, P.Oxy 5577 is significant: it shows that multiple ancient Christian groups identified someone named Mary as receiving special revelation from Jesus. This has real consequences for our understanding of Christian origins, as well as the authority given to women in some early Christian circles.

If you’ve already gotten wind of these new fragments, it’s likely that the fragment you’ve heard about is P.Oxy 5575. In an August Daily Beast article, Candida Moss of the University of Birmingham gives a thorough introduction to this papyrus. She writes, “Although the fragment does not include the phrase ‘Jesus said,’ it appears to be a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus. As the fragment is so short, it is difficult to determine exactly what kind of text it was.” Moss also addresses some initial speculation that this fragment was a portion of the sayings source Q, a theoretical lost written source of sayings of Jesus that was perhaps known to Matthew and Luke. Moss explains that P.Oxy 5575 cannot be Q, because it “departs from Matthew and Luke in small but important ways. It is, however, a sayings source.”

The editors of this papyrus date P.Oxy 5575 to the second century, but this dating has since been challenged (see below). The papyrus is quite fragmentary, so there is substantial guesswork involved in the following textual reconstruction:

. . . he died (?). [I tell] you: [do not] worry [about your life,] what you will eat, [or] about your body, what [you will wear.] For I tell you: [unless] you fast [from the world,] you will never find [the Kingdom,] and unless you . . . the world, you [will never . . .] the Father . . . the birds, how . . . and [your (?)] heavenly Father [feeds them (?).] You [also] therefore . . . [Consider the lilies,] how they grow . . . Solomon . . . in [his] glory . . . [if ] the Father [clothes] grass which dries up and is thrown into the oven, [he will clothe (?)] you . . . You [also (?)] therefore . . . for [your] Father [knows] . . . you need. [Instead (?)] seek [his kingdom (?), and all these things (?)] will be given [to you (?)] as well.

Daniel Wallace, one of the editors of the papyrus, notes a surprising aspect of the papyrus, one first observed by his graduate student Rory Crowley: these sayings have parallels in the Gospel of Thomas. In particular, the fragment recalls saying 27 of the Gospel of Thomas: “If you do not fast from the world, you will not find the Kingdom of God. And if you do not sabbatize the Sabbath, you will not see the Father.” Here, something resembling that apocryphal saying is unexpectedly folded between sayings of Jesus reminiscent of Matthew 6 and Luke 12. This new papyrus fragment also apparently begins with “he died,” which recalls saying 63 of the Gospel of Thomas: “There was a rich man who had much money. He said: ‘I will use my money so that I may sow and reap and plant and fill my storehouses with produce, so that I lack nothing.’ This was what he thought in his heart. And that very night the man died.”

I asked Mike Holmes, another of the papyrus’s editors, about the connection between these sayings and the Gospel of Thomas. He emphasized that much remains uncertain: “First, the wording of the fragment is not identical to Matthew, Luke, or Thomas, but only similar, and second, the fragment is very small.” As for the second-century date assigned to the papyrus, Holmes underlined that this is an approximate date based solely on its similarity of handwriting with other papyri: “When dating on the basis of a comparison of scribal hands, one deals with degrees of probability, not certainty.”

Very shortly after the papyrus was published, respected papyrologist Brent Nongbri challenged the second-century date. He did so by confirming the editors’ tentative suggestion that the scribe of these sayings was the exact same scribe as that of P.Oxy 4009—an Oxyrhynchus papyrus published in 1993, which preserves yet another previously unknown rewriting of gospel traditions. Pasquale Orsini, one of the world’s foremost paleographers of ancient Greek, has assigned P.Oxy 4009 to the fourth century, so it is possible that the editors of P.Oxy 5575 have leaned slightly early in their dating.

This papyrus has already caused a huge stir in New Testament studies, especially for those who assume that the four canonical gospels were static and carefully preserved from the beginning. This papyrus demonstrates that some early Christians were happy to mix and match words of Jesus, and some apparently gave equal weight to sayings that would be preserved only in the Gospel of Thomas. As Holmes explains, “in this significant respect, 5575 is unique among all known papyri.” (Although, as Ian Mills of Hamilton College points out in an article for the Text and Canon Institute, we do know of several other early Christian works that recombine familiar stories about Jesus.) Holmes underlines that “whether the ‘Thomas’ material came from the Gospel of Thomas, or a possible source of Thomas, or from some oral source cannot be determined. And the same may be said of the synoptic material: it could be from an oral source or a written one.”

To see a comparison of the new sayings fragment alongside sayings of Jesus known from other gospels, Goodacre has provided a helpful English synopsis of the fragment on his website and put it in parallel columns next to Matthew, Luke, and the Gospel of Thomas.

P.Oxy 5576, another fragment published in the latest Oxyrhynchus volume, describes Jesus uttering several apocalyptic sayings. Chapa edited this papyrus as well, and he dates the fragment to the third century. Again, the text itself could have been authored earlier, and again, papyrus dating is imprecise. Nongbri told me that “for 5576 and 5577, Chapa’s dates may well be correct, but they could also be a bit earlier or (especially in the case of 5576) a bit later.” Here is its reconstruction:

. . . and [he?] killed the tyrants who acted arrogantly against him.

Jesus says: “When you saw a flood of water, you made for yourselves a wooden ark and on it you rested. When you see a flood of water, make for yourselves another ark and rest on it . . .

. . . , but they will not even perceive my rest.

Jesus says: “Your time has become short, since we do not have the fire of flesh from the place of truth, nor, indeed, the fire unquenchable . . . from the same place . . .”

Chapa notes that this content is reminiscent of several themes found in the Nag Hammadi codices. For example, in Nag Hammadi texts like The Reality of the Rulers and The Concept of the Great Power, arrogant cosmic rulers decide to annihilate everything with a flood in a sort of rewriting of Genesis 6–7. These texts also refer to an ark, and many Nag Hammadi texts emphasize the concept of rest or repose.

When encountering ancient papyrus fragments with the words “Jesus says,” it is understandable to wonder whether Jesus actually spoke these words. In the case of P.Oxy 5576, it’s difficult to argue that this was an actual historical saying of Jesus, since only one papyrus preserves it and this gospel appears to be completely unknown otherwise. Moreover, it was quite common for later gnostic Christians to author such stories and attribute sayings to Jesus.

These three new fragments are fascinating for scholars of the New Testament and early Christianity, as well as for curious Christians. Has Mary’s long-lost vision from the Gospel of Mary finally come to light? Were the earliest Christians less strict in their copying of the gospels than has often been assumed? These texts remind us that the first centuries of Christianity were much more varied, and sometimes much stranger, than anyone has ever imagined.