The grace of apocalyptic imagination

As the depth of the climate crisis is revealed, our despair grows. But God hovers at the edge of doom.

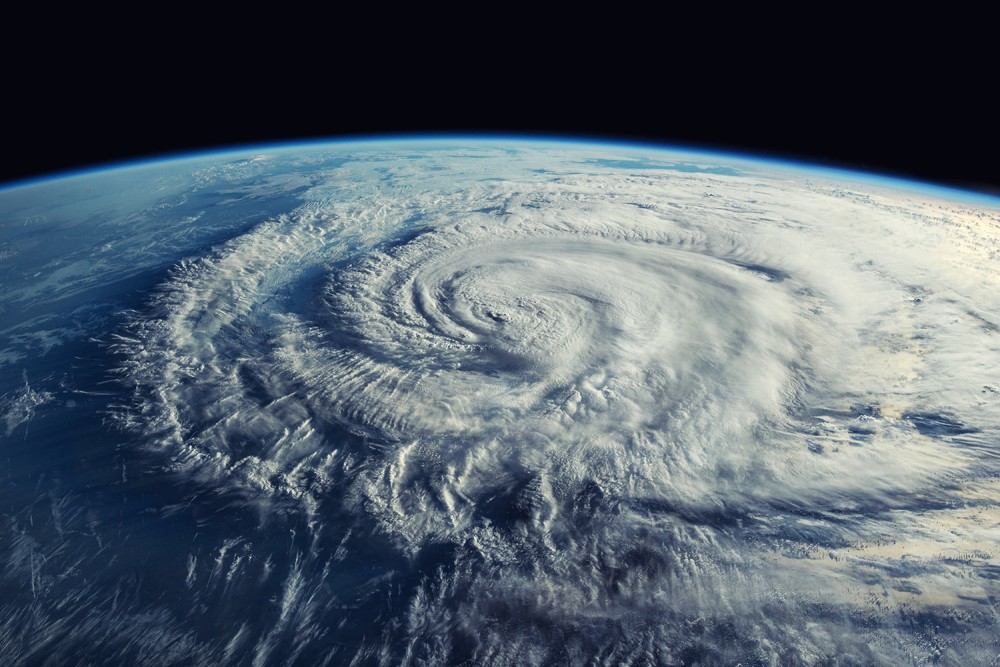

(Image: NASA / Evgeniy Trifonov / iStock / Getty)

As Hurricane Milton bore down on Florida’s Gulf Coast, North Carolina state climatologist Kathie Dello characterized the aftermath of Hurricane Helene as “apocalyptic destruction.” Helene dumped 31 inches of rain on a region of North Carolina considered relatively safe from extreme weather disasters. Such storms are increasingly unpredictable, affecting even inland areas where people don’t expect them.

Climate apocalypse seems to be our new shared reality. A 2021 survey found that 59 percent of teens and young adults were very worried about climate change, while 75 percent described the future as frightening. Apocalypse means revelation, and as the depth of the climate crisis is revealed, our despair grows.

But as Jack Holloway writes, “pessimism is part of the power of apocalyptic imagination.” Holloway traces the use of apocalyptic imagery in heavy metal music, from Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs” to Napalm Death’s “On the Brink of Extinction.” Knowing that the present world is doomed can be a gift, says Holloway, when it fuels the desire to bring about something better: “When things are cataclysmic and horrifying . . . we need daring, world-changing consciousness.”