Artists with office hours

Clergy stress is in the news again. Lately

there's been a lot of discussion about clergy health, well-being and

effectiveness. I found these issues personally pressing as the deadline for my

United Methodist conference's annual interviews approached. Pastors are asked

to reflect on the past year, set goals for the next and share their plans for

self-care and continuing education. All of this is growing more important and

more poignant for me since I've returned to work after the birth of my second

child. I find myself noticing how many nights a week I am out of the house, how

many days in a row I'm in the office, how many tasks fill my plate.

It's

not that I'm overworked or want to work less. It's not that I doubt my calling

or effectiveness or feel the judgment of my congregation or supervising pastors

weighing down on me. I don't expect each day to be rich and joyful, and I don't

feel my time is too valuable to do menial tasks, or that God would be better

served if I spent less time talking with people who stop by the office and more

time in prayer. If I fantasize about leaving my job, I give thanks that my

daydreams are usually occasioned by tasks that are quickly if begrudgingly

completed (composing teacher handbooks) or rarely required (justifying my

position to an anxious finance committee).

The

church needs clergy who are introspective and insightful about the nature of

their calling and principled and flexible in the practice of ministry. We need

clergy who are willing to give up a day off sometimes for the good of the

congregation and who know that it's

well-advised to play hooky sometimes. That's the balance I seek for me, for my

family, for my congregation, for God.

Many

of the recent articles about clergy burnout suggested that it's a symptom of

cognitive dissonance: pastors think their job ought to be a particular kind of

work and are frustrated when it ends up involving something else. I can see

that. I love professional ministry when it's centered on preaching, teaching

and pastoral care. When the bulk of my time is spent doing other things, I get

frustrated.

None

of the media coverage, however, offered a compelling description of the call to

ministry itself. The metaphor I prefer is that of the artist. Good artists have

both vision—a way of seeing what is and what might be—and the technical

skills to realize the vision. They might not pick up a brush or pen every

single day, but they never stop seeing. I am always a pastor, whether or not

I'm working: my ministry is who I am, my stance in the world, my relation to

God, my way of seeing other people.

On

days when I consider leaving the ministry, I am talked off the ledge by

realizing that leaving would require a whole new identity as a Christian—I

don't think I know how to be a Christian who isn't in leadership. But the days

that really drive me to the limit are those when I feel the disconnect between

the technical demands and the vision, when I am either all task with no end or

all goal and no motion.

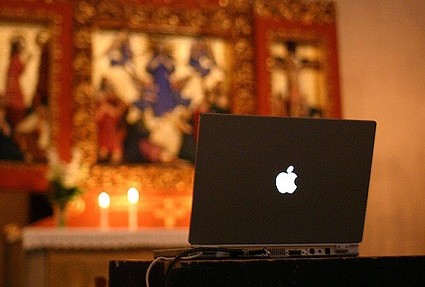

Of

course, if clergy are artists, we are artists with offices—and office hours. We

are to exercise our skills and vision, but we are accountable to the

call of God that may challenge that vision—and to the needs and expectations of

parishioners. For artists and pastors alike, there are any number of criteria

for judging success. The challenge is knowing which criteria to use, how to

weight them and whose evaluations to take to heart.