The Quest for Love from the World

Needing love as a pastor is a difficult thing to gauge. For while it is completely human to need love, we must also acknowledge this moment of rampant narcissism.

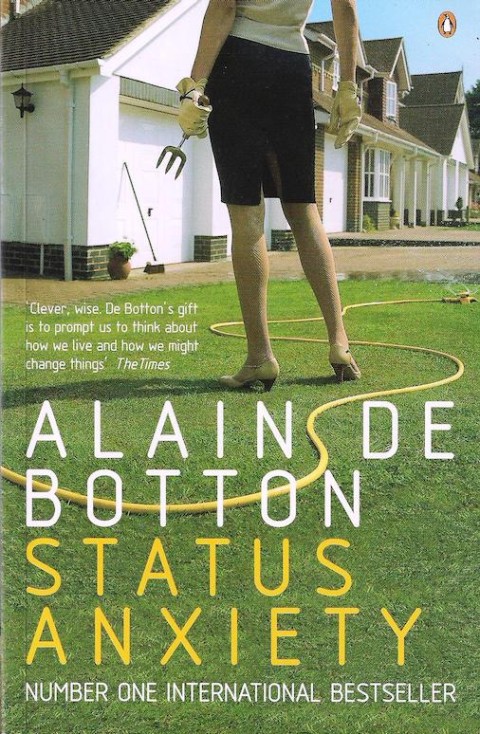

“Every adult life could be said to be defined by two great love stories,” Alain de Botton wrote, “The first—the story of our quest for sexual love—is well charted…. The second—our quest for love from the world—is a more secret and shameful tale.”

I’m part of an on-line writing group. A few of us went to a Writers’ Conference. It was one of those gatherings where you spend most of your time talking with someone who is looking over your shoulder for someone more important. As we reflected on the experience, Katherine Willis Pershey encouraged us to read Status Anxiety in order to understand what was happening with our weirdly shattered egos. It opened my eyes to so many things. It spoke to me, not only as a writer, but as a pastor as well.

De Botton defines status as “love from the world.” As I read his words, I realize that if the “quest for love from the world” is a disgraceful feeling for most people, it must be doubly so for pastors. Yet, as we build a beloved community, we will, at times, need love. I’ve spent enough years in therapy to know that a love that negates ourselves becomes unhealthy and lop-sided.

However, needing love as a pastor is a difficult thing to gauge. For while it is completely human to need love, we must also acknowledge this moment of rampant narcissism.

My daughter and I were on a walk, enjoying the crisp smell of a sunny winter afternoon. I saw a teenager, being photographed. She was an ordinary 16-year-old, but when the phone camera pointed at her, she whipped back her hair, puffed out her chest, and pivoted to the perfect angle. She put her hands on her hips and looked at the camera so coyly that she suddenly transformed into a 1950s pin-up girl.

I remembered the shy pictures of me at that age, hugging my chest, too embarrassed to look up.

Of course, someone being camera savvy in this era of ubiquitous lenses is not narcissism. That’s our simple, popularized notion of it. As we imagine the myth of Narcissus, the young hunter, entranced by his own reflection in the river, people point to selfies as a modern equivalent to his obsession.

There is a lot of misunderstanding out there. David Brooks wrote an odd piece about the “Morality of Selfism,” in which he not only displays that he’s really bad at satire, but he also mocks the basic tools for overcoming trauma—finding your voice, telling your story, and standing for justice. Perhaps Brooks hasn’t been through the devastation of abuse or systemic oppression, because the article seems to have a misunderstanding of narcissism and codependency at its core.

“Though often placed in a framework of self-love,” experts remind us that “narcissism is more about shame and self-hatred.” The actual signs of narcissism are more sinister than smiling for a camera—a lack of empathy, feelings of entitlement, exploitation of people, or condescension toward others.

So why do I think that narcissism is a problem right now?

While every mental health professional I know has told me that diagnosing a person from afar is unethical, from my unprofessional vantage point, it does seem that our president exhibits narcissistic tendencies. And our continued focus on him has to rub off on our society.

Then there’s this study that found that pastors have a higher rate of narcissism. From a small sample of 392 pastors from the Presbyterian Church in Canada (PCC), researchers report that 97 had diagnosable levels of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD). Almost one-third of all active PCC clergy had diagnosable NPD. This is a limited study, but it is worrisome enough that I hope more research is put into it.

How should we respond to all of this?

Surely some would react to the news about narcissistic pastors by saying that ministers need to have a servant’s heart.

On the contrary, I think that our Christian tradition of seeing pastors as servants has not helped us. Slavery is deplorable. Though it was common in Roman society and it used as a metaphor in Scripture, we have overwhelmingly determined that slavery is de-humanizing and violates the fact that we are made in the image of God. We fight against human trafficking and mourn the capture of small girls who are forced into domestic labor and sex work. So why do we continue to use one of humanity's greatest sins as a metaphor for ministry? We cannot cure self-hatred by demanding an attitude of dehumanization.

We serve, but we are not servants. Even the biblical witness is more complicated than we often present it.

Perhaps, pastors simply need to become more human—realizing our tendency toward shame and self-hatred, and understanding that we need love just like everyone else. Hopefully with that realization, we can learn how to find love in healthy ways and appreciate the love that we receive.