Turkey’s president builds an Islamic nationalism while amassing power

(The Christian Science Monitor) The builder-handyman and his fiancée, a cleaner, work for a small Istanbul company that has been going through tough times.

Harun Demir and Seniz Kaya could not look less religious, or less political. Yet they are the face of a new politics in Turkey, a staunchly held view of Islamic nationalism deliberately and painstakingly shaped by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP.

They believe—like many in their country—that Erdoğan’s heavy hand on everything from press freedom to engineering unprecedented presidential power is justified as the best path to solve Turkey’s constellation of problems. The country had 30 attacks by militants last year, faces a struggling economy, and is at war in southeast Turkey, Syria, and Iraq.

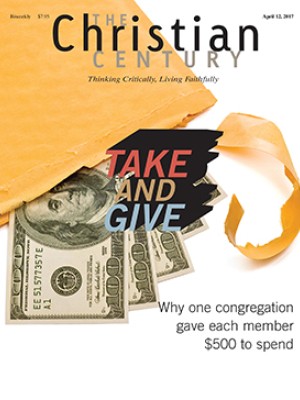

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“Now there seems to be a new pattern of leadership: Erdoğan, Russian president Putin, and Trump—they are not dictators, they are strongmen,” said Demir, approvingly. Erdoğan “is talking to people, he is doing it for the people. Maybe he is twisting some arms, but it is for a good cause.”

Turks should be patient and have faith in Erdoğan, Kaya said. “It’s our role as Turkish citizens to trust our leader.”

They shy away from the term “Islamic nationalism,” but say that in a diverse country religion can bind people together. They also echo officials when they say that Turkey is in the process of restoring its historical Ottoman influence as a leader of the Islamic world. Those references point to a moderate form of Islam, but with authoritarian rule. Indeed, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım has portrayed Erdoğan as a descendant of a well-regarded Ottoman-era sultan.

Critics charge that Erdoğan has dragged Turkey into a quagmire of social division, anti-Western sentiment, financial troubles, and multiple conflicts abroad. But the president has cast even the escalating attacks by the so-called Islamic State and Kurdish militants as a response to his country’s resurgent greatness.

“Turkey is under very serious attack both inside and outside,” Erdoğan said in January. “It is not because we are a weak country, but because we are a stronger and stronger country.”

Erdoğan, who has been in power for 15 years, has gradually turned his country away from the tradition of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who founded the modern state from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire in 1923. And there is little room for any competing views as the once ardently secular eastern anchor of NATO, which has aspired to membership in the European Union, clamps down on opponents and the media and moves away from democratic norms.

Recent polls indicate that Turkey’s conservative religious political bloc is a majority that will shape Turkish politics for the foreseeable future.

“They think that Turkey is facing big troubles, and they are correct on that, but they think those troubles are created by malicious forces conspiring against Turkey—that’s Erdoğan’s narrative, they buy into that,” said Mustafa Akyol, a Turkish analyst of politics and culture. “They think this conspiracy will only be undone by a very powerful, defiant leader, which is of course Erdoğan himself.”

Akyol, currently a senior fellow of the Freedom Project at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, and also author of The Islamic Jesus, noted that Erdoğan’s opponents have been jailed and exiled.

For decades, the military served as a self-declared bulwark of Turkish secularism, mounting four coups since 1960 to block Islamists from governing. But AKP rule has since neutered the military’s role in politics and made changes in the name of religion. Recently, for example, female army officers and cadets were officially allowed to wear headscarves as part of their uniforms. After a decades-long headscarf ban, there was a similar ruling for policewomen last year and, in 2013, for civil servants and in schools. And in February officials broke ground on a new mosque on the edge of Istanbul’s iconic Taksim Square, after years of controversy.

There has “always been a xenophobic, paranoid nationalism, but since it was based on Atatürk, it was also a secular nationalism,” Akyol said. “But now it is nationalism [with] a heavy dose of Islam, so it appeals to religious conservatives very strongly. . . . Turkish religious conservatives have always had this feeling that Turkey was the standard-bearer of Islamic civilization.”

The trend of Islamic nationalism has only accelerated since an attempted coup last July, in which Erdoğan’s call to loyalists to take to the streets brought the coup attempt to a swift end. The AKP organized a month of nightly rallies across the country that blended nationalist and Islamist imagery.

A state of emergency has been renewed twice so far, and according to some estimates 125,000 people have been fired or suspended from their jobs and nearly 50,000 arrested for suspected links to the coup attempt. In the political whirlwind, the AKP has convinced one opposition party to join it in rewriting the constitution to realize Erdoğan’s dream of creating an unassailable executive role—to its critics, a modern-day sultan.

Ahead of a national referendum on amendments to the constitution on April 16, an annual poll by Kadir Has University found a deeply divided society, but one with a coalescing majority.

Giving religion a higher profile has been part of the AKP’s agenda from the start. The number of mosques in the country has risen from 78,608 in 2006 to 86,762 in 2015, according to the Directorate of Religious Affairs.

“We are trying to make religion . . . a more vital part of life,” said Aydin Yiğman, the mufti of the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul and a ranking official in the Turkish state religious authority. He wears a suit and tie, not religious garb, and is mostly clean-shaven, in keeping with Turkey’s secular custom for officials since the 1920s.

“The goal of this education is so people learn the correct Islam,” he said.

He suggests that there is no greater religiosity among Turks now, yet the scene appears different from years past as the faithful these days spill onto the streets around mosques in some Istanbul districts during Friday prayers. New Sunday morning prayer meetings for youth attract up to 250 people a time.

“We don’t want people to think of the mosque only on Friday,” Yiğman said. “It is not something bad or under pressure. We want to build this upon love, so people are receptive to God’s call, because it is God’s call.”