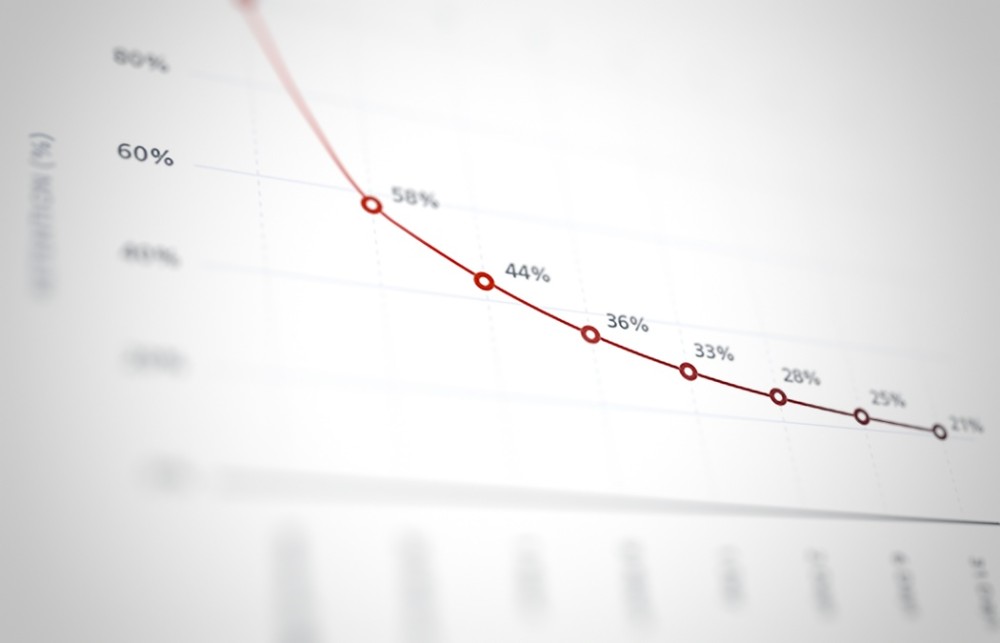

In 1885, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus published arguably the most famous finding of his career. Memory researchers still refer to his work on the “forgetting curve.”

The forgetting curve graphically illustrates how exponentially fast we forget newly acquired knowledge and information. The rate of forgetting slows over time; the steepest decline occurs in the first hours, leveling off somewhat after the first day. Frustratingly, we remember only a fraction of what our brains take in. Most facts, time lines, expressions, and even experiences fade into vague impressions much faster than we’d like to admit.

There’s a good reason our retention capacities are limited. We’d be unable to function were we to remember every detail of every day. The brain’s sorting mechanism for remembering and forgetting is a psychobiological necessity. With the exception of certain savants who appear to have effortless recall, our powers of memory are never going to be great.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Consider worship, where the forgetting curve is always in play. A worshiper’s inability to remember the particulars of worship even the day after a service concludes is striking. I have absolutely no idea what I preached about three weeks ago, nor do I recall the Bible reading or narrative theme for that day. I doubt that more than a handful of people in our congregation remember a single musical detail from that day. So much for worship radically altering lives!

And yet—this is a big yet—our forgetfulness does not diminish the significance of having worshiped. If anything, the cumulative effect of regular worship has a stunning impact on the shape of our lives. The whole repetitive act itself, not merely the remembered particulars, forms us into certain kinds of people. My character and empathy, my spirit and perspective, my joy and gratitude are all shaped by more than the details of what little I can remember from last week’s worship.

The same can be said of reading. What’s the point of reading, one might argue, if 95 percent of what we read is forgotten within hours or days? I can’t recall but a few particulars of the sweeping biography of Teddy Roosevelt I finished last week, or of the multiple news feeds I read just this morning. But that doesn’t mean reading is a waste of time. The habit of reading shapes and critically informs much of who we are. Reading enlarges the way we think and act and perceive the world.

At the Christian Century, we’re not naive enough to believe our content is so gripping as to alter the forgetting curve. Yet I’m certain the cumulative effect of the Century being a staple in your reading life contributes to the person you are in this world. Ask yourself: Would your heart and mind and outlook, not to mention your life of faith, be all that they are without the Christian Century?

Once a year on this page I implore you to consider making a gift to help underwrite this nonprofit journalistic ministry. Our pockets are not deep. We rely on reader support far beyond paid subscriptions. So please remember the need. Presuming this column may be forgotten by tomorrow, at least save the enclosed envelope (or donate online). Thanks for your generosity.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “We are what we read."