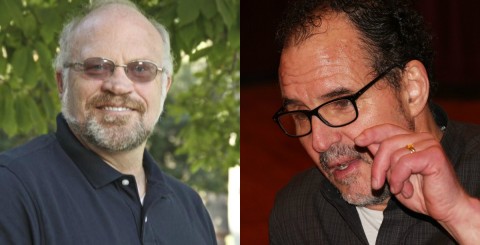

Terry Brensinger demoted as a seminary president, Greg Boyd let go as a visiting scholar

Fresno Pacific University announced it was taking Brensinger and Boyd out of their respective roles. The cause—and any connection between the two actions—is unclear.

Fresno Pacific University has demoted its seminary president and cut ties with three high-profile pastors affiliated with one of the school’s master’s programs amid concerns from constituents over those pastors’ theological positions.

Terry Brensinger, who has been president of Fresno Pacific Biblical Seminary since 2013, will leave his administrative role and become professor of pastoral education in January after a semester-long sabbatical. The seminary, which is affiliated with the Mennonite Brethren denominations in the U.S. and Canada, is accredited by the Association of Theological Schools and has fewer than 200 students.

Brensinger said donors made threats to withhold funding, especially in response to a book by Gregory A. Boyd, God of the Possible: A Biblical Introduction to the Open View of God, which advocates “open theism.” Boyd, an Anabaptist and senior pastor of Woodand Hills Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, is also author of the best seller The Myth of a Christian Nation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“If this would have happened before social media, this probably wouldn’t have happened at all, but people check Greg Boyd and see he wrote this and this,” Brensinger said.

The university announced that Boyd and two other pastors and authors, Brian Zahnd and Bruxy Cavey, are no longer connected with the seminary’s Master of Arts in Ministry, Leadership, and Culture program. A university press release attributed the changes to concerns by “a growing number of pastors and congregations” about the direction of the seminary and “some teaching positions of visiting lecturers.”

Tim Sullivan, who chairs the U.S. Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches Board of Faith and Life, confirmed that Boyd’s advocacy of open theism started raising concerns from pastors about two years ago, roughly when the program began. Statements about the atonement made by Cavey and Zahnd were also a factor.

“One of the biggest concerns was [that] it felt as though the seminary was beginning to lose touch with where the bulk of the denomination is in terms of what was being promoted and the visibility of those three visiting professors,” Sullivan said.

Boyd said he was not asked any questions prior to learning about the developments in early August a week before a gathering of some participants in the three-year masters’ program, which is predominantly online.

“I was just told that some of the bigger donors were getting some pressure from watchdogs of truth and righteousness or something, and the school’s funding was threatened,” he said. “It was unfortunate. The program was really good, and we had such high-quality students. The whole atmosphere was very kingdom-oriented, and it’s just sad that my view of the future got us canned for it.”

He clarified his perspective as affirming God’s omniscience and omnipotence but holding that future details are outside that scope.

“It’s nothing to do with the scope of God’s knowledge,” he said. “He knows perfectly everything that exists.”

Boyd said he had received letters of support from Mennonite Brethren pastors apologizing and worrying about their denomination losing Anabaptist distinctives and accommodating American fundamentalism. He described Brensinger’s administrative demotion as “tragic” and “discouraging.”

“I’m profoundly an evangelical who was a United Methodist who became an Anabaptist in college,” Brensinger said. “And at times I’ve found my Anabaptism is a liability as opposed to a welcome strength.”

Among the Mennonite Brethren, the situation is made more complex by the number of pastors who do not come from an Anabaptist background.

“It seems the denomination is much more diverse in that sense—I don’t want to say it negatively—with larger, growing constituencies that are not Anabaptist anymore,” Brensinger said.

Andrew Shaffer withdrew as a student when he heard about the changes, although he had completed 75 percent of the program. He and 21 of 23 other students in his cohort signed a letter to Fresno Pacific University president Joseph Jones.

“While we understand the university’s need for financial support, we believe that the university has clearly communicated to us through these changes that people with financial power are more important than FPU’s stated values of being a place of prophetic, Anabaptist witness that seeks academic excellence by engaging in scholarly dialogue,” Shaffer wrote by email.

Shaffer, who is pastor for transformation and administration at Pangea Church, a Brethren in Christ congregation in Seattle, said he heard 11 out of 18 students entering the program this fall had withdrawn. Most students in his cohort were drawn to the program because of the involvement of the three visiting lecturers, who were careful to note that opinions on controversial matters were not doctrine, he wrote.

“The way that they were suddenly removed with little to no dialogue with them or the students contributed just as much to my loss of trust in FPU and my decision to withdraw,” he wrote. —Mennonite World Review

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “People: Terry Brensinger, Greg Boyd.”