Rural chaplains support communities facing labor shortages, hate groups

On any given day, Bob Klingler, a rural chaplain in northwestern Pennsylvania, might be cleaning a flooded basement, facilitating an antiracist workshop, or leading worship from the bay of a livestock auction barn. Meanwhile, in Suffolk, England, rural chaplain Graham Miles could be answering a midnight phone call or helping a ewe give birth.

To Miles and Klingler, it’s all ministry.

According to Klingler, rural chaplaincy offers a different approach than other forms of chaplaincy. “We tend to work on a more practical level,” said Klingler. “We’re helping people to find new ways to make money, we’re educating people, we’re trying to advocate for things like rural health care or transportation in rural areas.”

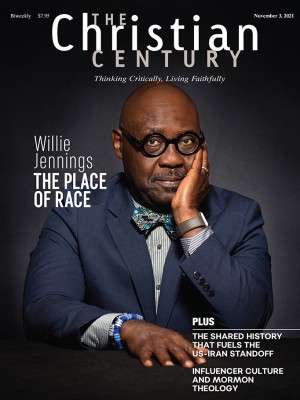

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

An ordained elder in the United Methodist Church, Klingler pastors a six-church cooperative ministry south of Erie, Pennsylvania, in addition to his chaplaincy work. “On committees, I tend to be the voice that speaks up and says, ‘Yes, but what about the folks outside the cities? What are you doing in the rural areas?’” said Klingler.

Such advocacy is vital. Today, rural communities are facing an onslaught of pandemic-era challenges caused by labor shortages, ecological crises, and changes in supply and demand.

“People don’t realize farmers are probably not making enough personal income, and a lot of farm families end up getting food stamps,” said Klingler. “In a lot of cases, dairy farmers are losing money on milk these days. So rural chaplains are a way to have people on the ground who can deal with those sorts of issues and help train others.”

Klingler was one of the first to be certified as a rural chaplain by the Rural Chaplains Association, which formed in 1991 in response to the US farm crisis of the 1980s. A sudden drop in the price of land caused the nation’s farm debt to double between 1978 and 1984, and thousands of farms faced financial collapse. According to the National Farm Medicine Center, more than 900 farmers died by suicide in five Upper Midwest states during the 1980s.

Klingler said the crisis also fed the growth of hate groups, which gained sympathy by using intimidation—at times with weapons—to block sheriffs’ sales of foreclosed farmland. It was out of this context that the UMC provided a grant to start the Rural Chaplains Association, now a self-funded nonprofit that provides training and networking opportunities for 72 rural chaplains around the world.

The association requires applicants to attend annual meetings and meet with a review committee before being approved for certification. Ordination is not a requirement, and while currently all association members are Christians, Judy Matheny, an administrative staff person at the association, said they would be open to having applicants from other faith traditions.

While farmers in places like California endured a drought-stricken summer, Klingler said the farmers in his area have had an ideal growing season. Rather than focusing on agriculture, Klingler has been working to quell the spread of hate groups, which are prevalent in the area.

Following the 2020 election, a KKK group came through the area distributing invitations to join them. Klingler was part of a rally that responded to the hate group and has led seminars and study groups on antiracism.

In Fairmont, West Virginia, rural chaplain Dick Bowyer partnered with local pastors and young people to put together a protest and prayer service in response to the killing of George Floyd.

Bowyer said the young people in his small, rural community are especially vulnerable to challenges like addictions. “West Virginia still ranks number one in terms of the opioid crisis,” said Bowyer.

Between 1999 and 2015, the rate of deaths due to opioids quadrupled in rural communities among people age 18 to 25, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data collected by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in 2018 showed that in West Virginia there are more than 42 opioid-involved overdose deaths per 100,000 people, the most of any state.

Though Bowyer is largely retired, as a rural chaplain he partners with local organizations in the former mining town to provide programs and jobs for those dealing with substance abuse and unemployment. One ongoing project involves the conversion of a former church into a community center.

Miles is not affiliated with the Rural Chaplains Association. Instead, he was licensed to become a rural chaplain through the Church of England in 2019. Miles says his farming background allows him both to empathize with farmers’ struggles and to provide hands-on support. He once helped a farmer with lambing at three in the morning.

“I don’t go onto the farm preaching, and I don’t wear a collar, which I find helps sometimes,” said Miles. “It’s just about coming alongside them. Nine times out of ten, I just have to listen.”

Listening has been especially important during the pandemic, when Miles says farmers in Suffolk have faced extreme isolation. “I’ve been getting phone calls from farmers, with loneliness, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts,” he said. “The phone calls come in late at night, after 11, 12.”

In addition to isolation, the pandemic has also ushered in some unexpected challenges in rural communities. Miles said the UK is experiencing a delivery driver shortage, sending sugar beet farmers in the UK scrambling to figure out how to deliver their crops.

In Klingler’s Pennsylvania community, locals are seeing an influx of eggs that are impacting the local economy.

“A lot of folks in the area, because of the pandemic, started raising chickens,” said Klingler. “And so those folks who depended on selling eggs as part of their living now have more competition, and the prices have just plummeted at the local auction house.”

Klingler noted rural chaplains can act as translators for pastors who arrive in rural communities without any previous exposure. Their spiritual support and practical expertise can make a significant impact on communities where people often feel overlooked.

“The rural communities are the heartland of this country,” said Klingler. “And there’s a lot of really fine people out here that really feel like they get left behind.” —Religion News Service