Is religion good for you? The answer is complicated, new global Gallup report finds.

A new report from Gallup finds that religious people around the world report being more positive, have more social support, and are more involved in their communities than those who are not religious.

The study, based on 10 years of data, also finds the well-being of religious people varies from country to country and is often hard to measure. Even if researchers find that religion is good for you, people who are not religious may not care about its benefits or want anything to do with it.

“Gallup World Poll data from 2012-2022 find, on a number of wellbeing measures, that people who are religious have better wellbeing than people who are not,” according to the report, which was published Tuesday.

The study included data about nine aspects of people’s lives, from their positive interactions with others and their social life to their civic engagement and physical health. Each of the nine indexes included a score of 0 to 100, based on answers to a series of questions.

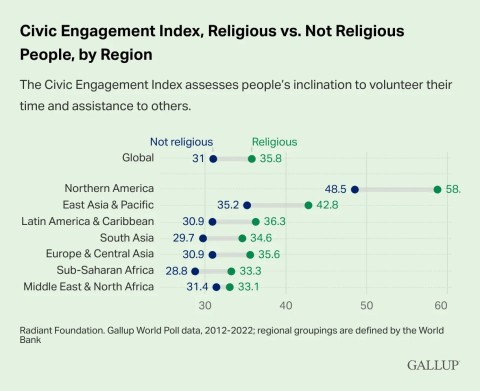

For the positive experience index, respondents were asked questions such as “Did you smile or laugh today?” and “Were you treated with respect?” For civic engagement, they were asked questions about whether they gave to charity or helped a stranger. The physical health index asked if they had health issues that kept them from doing things people their age usually do and whether they were in physical pain. For community basics, they were asked about housing and infrastructure.

Religious people scored higher on five of Gallup’s indexes: social life (77.6 compared with 73.7 for nonreligious people), positive experience (69 to 65), community basics (59.7 to 55.6), optimism (49.4 to 48.4), and civic engagement (35.8 to 31).

They scored about the same as nonreligious people in two indexes: a “life evaluation” of whether they were thriving or suffering and their local economic confidence.

Religious people scored lower on two indexes: negative experience and physical health.

The differences between religious and nonreligious people were most prominent in highly religious countries.

Researchers noted that even small differences can have a significant impact on a global scale.

“Each one-point difference in index scores between religious and nonreligious people represents an effect for an estimated 40 million adults worldwide,” according to the report. “For example, the four-point difference between religious and nonreligious people on the Positive Experience Index means that an estimated 160 million more adults worldwide have positive experiences than would be the case if those adults were not religious.”

The report suggests religion and spirituality could be a possible asset in dealing with the mental health crisis in many countries. However, they noted, the number of people interested in or involved in religion is declining.

For the report, Gallup partnered with the Radiant Foundation, which promotes a positive view of religion and spirituality and is associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Jeff Jones, Gallup poll senior editor, said measuring the impact of religion and spirituality on wellness is complicated, especially as people become less religious and the way they practice spirituality evolves.

“With the changing nature of religious landscapes and spiritual practice, it can make quantitative measurement amid the changes challenging, as the traditional forms of spirituality — namely, attending formal religious services, are becoming less common and people are seeking other ways to fulfill their spiritual needs,” Jones said in an email.

The report, which also includes quotes from experts and a review of past research on the connection between wellness and religion, notes that even as researchers become more aware of the positive outcomes of religion, people are less interested in religion around the world.

While they have no polling data on the decline of religion, the report suggests several causes for that decline—including growing polarization that pits religious and nonreligious people against each other. Nonreligious people at times see religious people as a threat. Religious people, especially from larger faith groups, can wield their power in ways that others see as harmful.

“Religious groups and individuals — particularly from the dominant religious group in a society — who are hostile to other religious groups may promote a cultural context that is harmful to the wellbeing of those outside the group. Resentment toward the dominant group may also tune people out to their messages, both those that are harmful (out‑group animosity) but also that are helpful (serving others),” the report states. —Religion News Service