How the Southern Baptist report almost didn’t happen

For three minutes last summer, a call to investigate how Southern Baptist leaders have dealt with sexual abuse was dead in the water.

Then a little-known denominational bylaw and a pastor from Indiana saved it.

“I just had to do it,” said Todd Benkert, pastor of Oak Creek Community Church in Mishawaka, Indiana. “It was me or nobody.”

During a morning business session at the Southern Baptist Convention’s June 2021 annual meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, Southern Baptist leaders announced that a motion to set up an independent sexual abuse investigation was being tabled.

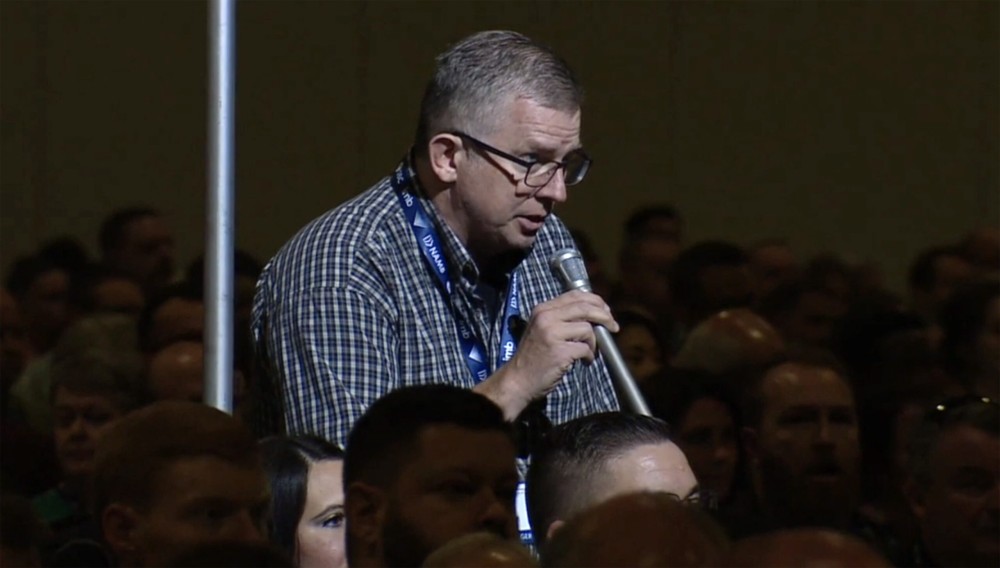

J. D. Greear, the president at the time, was ready to move on when Benkert stood up at a microphone with a motion of his own, based on another section of bylaw 26.

“I would like the opportunity to make a motion to overrule the Committee on Order of Business at the appropriate time,” he said.

Benkert’s motion was met with applause, then a second, and then almost all of the 15,000 local church delegates raised their yellow voting cards in the air—far more than the two-thirds majority needed to overrule the committee.

Those delegates would later approve the abuse investigation. A report from that investigation, released on May 22, would show that for decades Executive Committee leaders had done everything in their power to protect the institution from liability.

“In service of this goal, survivors and others who reported abuse were ignored, disbelieved, or met with the constant refrain that the SBC could take no action due to its polity regarding church autonomy—even if it meant that convicted molesters continued in ministry with no notice or warning to their current church or congregation,” the report concluded.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The report, compiled by outside investigation firm Guidepost Solutions, was an “apocalypse,” according to former SBC ethicist Russell Moore. Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, called it a sign of God’s judgment on the nation’s largest Protestant denomination.

The existence of the abuse report is a triumph of congregational polity—the idea that people in the pews should have the final say, rather than leaders—and the fierce determination of survivors and advocates to say enough was enough.

And yet, the abuse investigation almost never happened.

From the moment it was proposed, Executive Committee leaders actively tried to either shut the report down or defang it so the committee’s secrets would never be known.

The story of the report begins in October 2019, when Rachael Denhollander, an attorney and advocate, spoke at the SBC Caring Well conference on addressing sexual abuse. During the conference Denhollander criticized SBC leaders for mistreating a survivor named Jen Lyell.

That led to a backlash from leaders like Ronnie Floyd, then president of the Executive Committee. In a meeting with Moore after that conference, Floyd said, “I am not concerned about anything survivors can say,” according to a recording of the meeting.

Moore later wrote to trustees of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission about his clashes with other Southern Baptists, saying the culture of SBC leaders was unsafe for abuse survivors. His letter became public when it was leaked to Religion News Service.

After reading Moore’s letter, Grant Gaines, a pastor from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, said he sent a text to his friend Ronnie Parrott, a pastor in North Carolina, saying the Executive Committee “had some explaining to do.”

“He said to me, ‘Yeah, but who is going to get them to explain it?’” Gaines said in an interview.

The two decided to draft a motion for the SBC’s 2021 annual meeting to set up an investigation to do just that. They consulted with experts on SBC governance to make sure the motion was in order and talked to advocates about what was needed.

Among the suggestions: getting access to communication between SBC leaders and their lawyers.

From the beginning, Gaines said, Executive Committee members were against any kind of independent investigation or the idea of waiving attorney-client privilege. Less than an hour before Gaines and Parrott were set to make their motion, Floyd and another staffer met with them, asking them to change it. In particular, Gaines said, they wanted to remove any mention of waiving privilege.

Gaines and Parrott refused.

When Gaines later learned that the motion would likely be referred to the Executive Committee, he made a speech from the floor of the convention, urging the Executive Committee to do the right thing.

“Because the Executive Committee is the one under investigation, the Executive Committee can’t be the ones that control the investigation,” he said. “That would be the wrong way to do this.”

Greear was sympathetic to Gaines’s concerns. Still, the bylaws seemed to dictate that the issue should be referred to the Executive Committee. The motion’s fate seemed sealed.

At the time, Gaines had no idea that delegates could overrule the decision to refer his motion. He also did not know Benkert was waiting in the wings. A pastor for more than two decades, Benkert said he had been at other church meetings where decisions had been overruled. So he made a split-second decision to get to a microphone.

“If I had not got up, it was dead,” he said. “I’m glad God used me.”

Getting the motion passed proved to be only half the battle. Though Floyd told delegates the committee would not oppose the motion, soon after the meeting he went to work to regain control of the investigation.

In public statements and letters to Executive Committee members ahead of their fall meeting, where they would vote on whether to waive privilege, Floyd tried to dissuade them. The Executive Committee would eventually hold three hotly contested meetings over the issue of waiving privilege, with a vote to do so failing repeatedly. The committee approved the waiver in a third meeting, on October 5, 2021.

After the meeting, 16 committee members resigned in protest. Floyd quit as well, saying his reputation was at stake.

Bruce Frank, who chaired the task force that hired Guidepost, said the report revealed why some Executive Committee staffers and members did not want communications with lawyers made public. Not everyone who voted against waiving privilege had nefarious intent, he said. But some knew what they were hiding.

For example, he said, the report revealed that Executive Committee staff kept an informal list of abusers while claiming the SBC could not set up a database to track abusers, something he called beyond belief.

Lyell, a former vice president for Lifeway Christian Resources, the Southern Baptist publisher, doubts anything will change, even after the report. Lyell supported the abuse investigation but said it revealed only the tip of the iceberg and that the SBC was inherently flawed.

“That cannot be fixed,” she said, adding that any reforms put in place at the June 12–15 SBC meeting in Anaheim, California, will be too little, too late.

“If they think they can go to Anaheim and change the script or throw in some prayer, they have lost their minds,” she said. “I guarantee you that the Jesus who’s in the scriptures would shut Anaheim down. Period.” —Religion News Service