Clergy visits give hope to ICE detainees, but access is inconsistent

All prisoners in the United States have religious rights, undocumented or not. But human rights groups and a government inspector report concerns at various ICE detention centers, such as the right to worship being denied or disrupted.

Roberto Rauda went to a Connecticut courthouse in May to pay a fine for carrying an open container of beer. Instead he was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in a routine sweep and ended up in the Bristol County House of Corrections in Massachusetts.

Rauda, 37, who is undocumented, came to New York from El Salvador as a teen and later found work in construction and at a lobster processing plant. He was released in September after members of the advocacy group Unidos Sin Fronteras paid his legal fees and $3,500 bail.

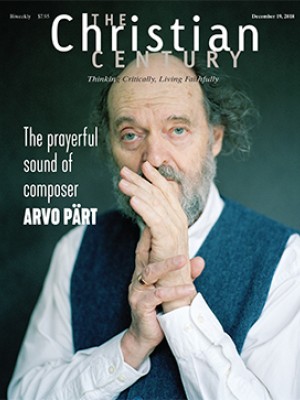

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Sitting in his lawyer’s living room, Rauda grimly recalled conditions at the Massachusetts facility, such as cramped sleeping arrangements and inedible food. His face softened as he recounted how prayer helped him endure.

“We had a Catholic priest who came every two weeks, and we would get together in a room to pray and sing hymns,” Rauda said through a translator. “I was scared I wouldn’t get out, that my wife would be left alone, and I prayed to God that she would be all right.”

For detainees, clergy and faith can be glimmers of hope in a climate of deep despair. But among the more than 39,000 undocumented immigrants locked up on any given day in ICE detention centers nationally—the highest number in history—access to clergy, religious material, and worship services is inconsistent or absent altogether for many.

At the Northeast Ohio Correctional Center in Youngstown, Ohio, several detainees told their attorneys that they rarely saw clergy. “The last time I saw a priest was when I was in El Salvador,” said one detainee incarcerated at NEOCC, which is operated by CoreCivic, one of the largest private corrections companies in the United States.

A 30-year-old Brazilian asylum seeker who was transferred to NEOCC from San Antonio said that in Texas a pastor would visit on Sundays but the Ohio facility only showed a video.

“I would like to have a pastor come every Sunday,” he said. “We need this, because it helps us when we’re suffering a lot and don’t know what’s going on.”

Attorneys working for the International Institute of Akron, an immigration legal services and refugee resettlement organization which helped arrange interviews, asked for anonymity on their clients’ behalf.

NEOCC has a full-time chaplain and a part-time chaplain, according to Rodney E. King, CoreCivic manager of public affairs. He wrote in an email that there are six active volunteers who currently serve evangelical Christians, Catholics, Muslims, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Sikhs for the U.S. Marshals Service and the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction. One of those, the Catholic volunteer, has recently been cleared by ICE to minister to detainees, and approvals are pending for a Muslim and a Sikh, King wrote.

But reports from human rights organizations, immigrant advocacy groups, and the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general chronicle religious rights concerns at various ICE detention centers, including reports of prison guards mocking some faiths and of detainees’ rights to worship being denied or disrupted.

The religious rights of all prisoners in the United States, undocumented or not, are protected under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000. Additionally, ICE National Detention Standards of 2011 require that detainees “shall have regular opportunities to participate in practices of their religious faiths” and that every facility have a chaplain or religious services coordinator to “recruit external clergy or religious service providers” for detainees whose faiths are not represented by on-site clergy.

The sheer number of detainees can make it difficult, even impossible, for staff chaplains alone to minister to all. NEOCC can hold more than 2,000 prisoners, including as many as 352 detainees.

Without visiting volunteer clergy, a chaplain could only minister to all inmates for less than two minutes per week, said Dustin White, pastor at Radial Church in Canton, Ohio. White was among five clergy arrested outside NEOCC in August after they refused to leave unless allowed to offer religious support to detainees there. White attempted to go through the proper channels of applying to be a visiting clergy, but the process took months before it dead-ended. And the application to become a CoreCivic volunteer raised red flags for White, who said he philosophically opposes for-profit prisons.

“CoreCivic is incompatible with my faith,” he said.

Baptist minister Alan Cross of Montgomery, Alabama, said he was surprised to learn that visits with detainees at the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, would only be through glass windows or via video screen.

“I’ve done jail ministry before and been able to have contact with inmates,” Cross said. “This is not how ministry is supposed to be.”

Gathering for worship has also been problematic, according to ICE’s inspector general’s office. At Stewart, staff have reportedly delayed or interrupted Muslim prayer times.

At the ICE processing center in Adelanto, California, a privately owned facility run by the GEO Group, Christian women gathering to pray, sing, or read the Bible were ordered to disperse, according to interviews conducted by Freedom for Immigrants, a nonprofit organization that monitors human and civil rights abuses at 55 of the largest ICE detention centers.

“There’s a rule at some of these facilities that groups must be facilitated by an outside volunteer, so if there’s no outside volunteer, there cannot be any group discussions,” said Christina Fialho, Freedom for Immigrants’ cofounder and co-executive director.

Fialho said clergy visits and the frequency of religious services vary from one detention center to the next.

At the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, another GEO Group facility, pastoral visits and Christian, Muslim, and Sikh services regularly take place, according to Jose-Luis Bonilla, coordinator for volunteer visits at the Seattle office of World Relief, a nonprofit serving refugees and asylum seekers.

Some clergy have found that the best way to gain access to detention facilities is to foster relationships with wardens or resident chaplains. Delle McCormick, senior pastor at Rincon Congregational Church in Tucson, Arizona, who ministered to detained children at a government-contracted shelter in Tucson in 2016–2017, found that it was possible, once inside, to gain the trust of prison authorities.

“As time went by, the staff really became supportive of the worship service,” McCormick said. Singing was a popular activity during worship services and even some guards were moved to join in from the sidelines.

McCormick recalled the children, mostly from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, singing “about making their way through the desert and the perils of the desert, and the kids would sob,” she said. “There was a great amount of collective grief and lamentation.” —Religion News Service

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Clergy visits give hope to ICE detainees, but access is inconsistent.”