Black Church Food Security Network brings fresh food to Baltimore

A group of Baltimore congregations is connecting with black farmers to promote healthy eating and economic empowerment.

Heber Brown III can speak with conviction about eggs. And not just any eggs. Free-range eggs that he had ferried up Interstate 95 the previous day to extend the work of his Black Church Food Security Network in Baltimore.

“I’ve never thought so much about eggs in my life before,” he said as he recalled his weekend buying eggs from black farmers in North Carolina and selling them to restaurants in Baltimore for the first time. He also saved some half dozens to sell for $2 after worship at Pleasant Hope Baptist Church, a congregation of about 80 people.

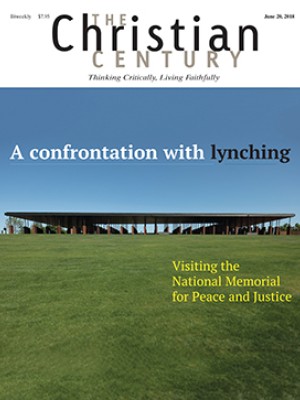

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“The cage increases the anxiety of the chicken,” said the 37-year-old pastor and “beginner farmer,” recalling what he learned from experts two states away. “You want a chicken to be cool, calm, and collected and eating what God made them to eat because that’s going to result in a better egg at the end of the day.”

The network’s goal is to provide alternatives to the less nutritious and more expensive foods sold at convenience stores in neighborhoods that don’t have good access to groceries. In addition to providing healthy food to hungry people in a majority-black city, the network builds economic power in urban and rural churches that can grow their own food and connect with black farmers in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.

“We thank God for food pantries, we thank God for soup kitchens, we thank God for food banks,” Brown said in a sermon. “But food banks, soup kitchens, and food pantries will not change the underlying conditions that have our community hungry in the first place.”

Brown, who wears a red, green, and black stole with West African symbols when he’s in the pulpit and a Baltimore Orioles baseball cap when he’s not, is finding that a growing number of people are open to his message, which combines economic, health, and environmental justice. He spoke to black Christian clergy at the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference in February in Memphis, Tennessee, and to students and faculty at the predominantly white Methodist Theological School in Ohio in April.

Brown’s church began a garden in 2011 after Brown sat by too many hospital beds of congregants with diet-related illnesses: “I wanted to do something more than praying and providing scripture.”

Then, in 2015, he was pressed into grocery delivery when Baltimore erupted after a young black man named Freddie Gray died in police custody. Schools and convenience stores were closed, reducing food access for children and adults, and people remembered the church with the garden in its front yard. He connected with farmers, turned his church’s multipurpose room into a food-processing area, and delivered food with his church van for a couple of weeks.

“We had the beginnings of a system that up to that point only existed in my head,” he said. “The uprising really pushed that idea into the real world.”

Today the network includes ten black churches, and he predicts it will double this year as more congregations start gardens on their properties. Brown is purchasing items churches don’t grow in their gardens from farmers, testing how church members like various foods using free samples, and planning to sell more of the products that appeal to them. Any profits from the farm produce sales go back into the network.

The pastor and activist also has been outspoken on how racism, prison reform, poverty, and the education of black youth relate to environmental justice.

“If you talk about food and food systems you bump into every other issue of concern,” said the minister, who is taking classes to learn about farming even as he is concerned about the lack of grocery stores in many neighborhoods and the quality of water in Baltimore’s public schools.

Derek Hicks, a scholar of religion, food, and black culture, said Brown’s work is revitalizing a long tradition in which African American churches have supplied food to their communities.

“What makes Heber’s model through the Black Church Food Security Network powerful is that it’s really centered on enfranchisement of the church and of the community,” said Hicks, a professor at Wake Forest University School of Divinity. The efforts “ensure the viability of the community . . . by way of nutrition and by way, ultimately, of financial viability.”

That focus on self-reliance extends to farmers who are partnering with the network.

“The connection with Dr. Brown, I’m telling you, was God-sent,” said Maxine White, executive director of the Coalition for Healthier Eating, based in Bethel, North Carolina, which connects mostly black farmers with consumers who can least afford to purchase nutritious food.

Her four-year-old organization works with farmers to process the food at its facility, allowing it to sell the products for a lower price than grocery stores. Brown’s recent purchase of 1,200 eggs was the coalition’s first connection with a church network.

In Baltimore, Bill Roberts, a deacon and master gardener, started his church’s garden in 2011 and joined the network a couple of years ago. His nondenominational New Creation Christian Church hosted the second annual season launch of Brown’s network in March, where about 90 people from six churches gathered to learn about starting or continuing gardens.

“As churches realize the impact they can have on one another, the education that can come from this, the elimination of the food deserts,” Roberts said, “we can eliminate those things that cause disease. —Religion News Service

A version of this article, which was edited on June 13, appears in the print edition under the title “Black church network builds food security, economic empowerment.”