Amid detentions and deportation, sanctuary movement persists

Three Indonesian Christians moved into their church in New Jersey—one of more than 30 congregations sheltering people facing deportation.

Congregations in the sanctuary movement continue to offer people refuge in their buildings, as others protest detention and deportation of their members and the breaking apart of families.

Two members of Judson Memorial Church in New York City who have been leaders in the New Sanctuary Coalition of NYC were detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in January, and one of them was deported days later.

“Our immigrant rights leaders are being targeted because they refuse to be silenced,” said Kaji Douša, pastor of Park Avenue Christian Church and coalition cochair.

Douša had accompanied Ravi Ragbir, coalition executive director, when he went to his ICE check-ins for the past nine years.

“Ravi has never been a risk,” she told United Church News. “He has convinced other immigrants to come out of the shadows.”

Ragbir was detained on January 11 after a routine check-in with ICE. He came to the United States from Trinidad in 1991 on a visitor’s visa and was granted permanent residency in 1994. He was ordered deported in 2006 based on a conviction for wire fraud, a financial crime involving the use of information technology. He served his sentence but has asked the court to reverse his conviction based on errors in his trial. Ragbir, who is married to a U.S. citizen, was released from detention on January 29 by a federal judge’s order and is currently appealing his deportation.

Jean Montrevil, coalition cofounder and another Judson Memorial Church member, was deported to Haiti on January 16.

“Jean came here over 30 years ago, had a minor drug charge in his teens, served his time, and just wanted a chance to start a life in the country he loved,” said Ted Dawson, a member of the Judson Immigration Task Force.

Judson members had also accompanied Montrevil to his ICE check-ins for more than ten years.

Donna Schaper, senior minister, said the church and the sanctuary coalition are especially concerned for Montrevil’s children.

“It is hard for them to trust democracy or government when actions like this occur,” she said. “To be living in this country without an offense for two decades, checking in every week—and then to be arrested in front of your own home—this is not the country we know and love.”

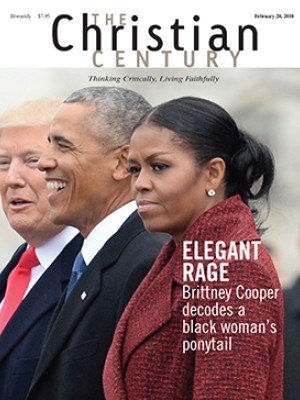

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In North Carolina, Congregational United Church of Christ in Greensboro began giving sanctuary to a second person facing a deportation order. Oscar Canales, 34, who owns a roofing company and employs many U.S. citizens, came to Greensboro from El Salvador in 2005.

“My daughters get upset when I tell them I might have to leave,” he said. “I just want to keep being near them and to keep my obligations to my clients and my employees.”

Canales was first detained by ICE in 2013 after a minor car accident in North Carolina. The responding police officer called ICE, and Canales was incarcerated for six weeks in Georgia before he was released with a stay of deportation and ordered to check in annually.

Since then, he has reported to ICE every year without incident, until this past October. Agents reinstated his order of deportation, fitted him with an ankle monitor, and told him he had to return to El Salvador by January 18. That day, the church notified ICE and the local police that Canales would be at the church instead.

Last year Congregational UCC offered sanctuary to Minerva Cisneros Garcia, along with her two youngest children, from June until October, when an immigration judge in Texas cancelled her deportation order and freed her to return to her home in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. However, a few months ago ICE informed Garcia that they are still going to pursue a case against her. Garcia is wearing an ankle monitor and has a court date in November.

In nearby Cary, Greenwood Forest Baptist Church has opposed the detention of Gilles Bikindou, a member of the church since 2006, Baptist News Global reported. The church fears he could die without access to a medication that is not available outside of the United States and Canada.

“ICE has shown no regard for Gilles’s rights or health,” said Lauren Efird, pastor of Greenwood Forest Baptist.

Bikindou came to the United States from the Republic of the Congo on an educational visa and applied for and was denied asylum, Baptist News reported. He received documents permitting him to work, drive, and live in the United States, which were renewed through 2017. He was arrested January 9 at a check-in.

In New Jersey, the Reformed Church of Highland Park is one of more than 30 congregations across the nation that are offering sanctuary to people facing deportation, according to the count kept by Church World Service.

Harry Pangemanan, an elder at the church, began living in the building in January. He spent nine months in 2012 under similar circumstances. Two other Indonesian Christians who fear persecution, Arthur Jemmy and Yohanes Tasik, were already living there. The two men were arrested last month after they dropped their children off at school.

In early February, a federal judge temporarily halted deportation proceedings against Indonesian Christians who are seeking to gain legal status, in response to a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union. Both sides were ordered to file briefs in the following month. A spokesman for ICE’s Newark office didn’t return a message seeking comment.

In the meantime, Pangemanan has been staying in a room that doubles as the church’s children’s library. His family joined him recently after his name was included in news reports and their home was broken into and vandalized.

Pangemanan came to the country in 1993 on a tourist visa that was to lapse in five years, he said. He had not been aware he had one year to apply for asylum. At the time, it didn’t seem to matter.

“Nobody asked you, as long as you are a good man, you work hard and help your company, and you pay your taxes,” he said. “You’re working like everybody else, you don’t bother anybody. Then everything changed after September 11.”

Authorities began requiring noncitizen men and boys from Muslim-majority countries to register and be photographed and fingerprinted. Pangemanan and Jemmy said they complied and have repeatedly tried without success to gain legal status since then, citing persecution in Indonesia.

“A thousand churches were burned to the ground between 1996 and 2003,” said Seth Kaper-Dale, copastor of the Reformed church. “Some islands are safer than others, but it’s too simple to say it’s safe now.”

FOLLOWING UP (Updated May 20, 2019): Despite the efforts of Greenwood Forest Baptist Church in Cary, North Carolina, to prevent longtime member Gilles Bikindou, 58, from being deported—as well as appeals from two members of Congress and a doctor concerned about Bikindou’s medical condition—U.S. immigration officials sent him back to the Republic of Congo on February 23, according to Baptist News Global.

Greenwood Forest Baptist is continuing to support Bikindou through their Missions Assistance Fund.

“Something is happening here within our walls and far beyond our walls because of Gilles’s story,” said Stephen Stacks, associate pastor of worship and faith formation. “Before this happened, we may have been able to bury our heads in the sand about what is happening to our immigrant brothers and sisters in our country, but Gilles has made sure we have heard the gospel call.”

Sean Gallagher, director of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office in Atlanta, wrote in a statement that Bikindou came to the U.S. on an exchange student visa, applied for political asylum, was denied, and was living under an order of supervision.

Concerning Bikindou’s medical concerns, Gallagher said government doctors believe his needs “could be fully addressed in the Republic of Congo.”

Minerva Cisneros Garcia in North Carolina received a green card on May 2, 2019, reported UCNews. A federal immigration judge granted the mother of three the legal status of permanent resident.

“She’s going to work on citizenship,” Julie Peeples, the church’s senior minister, told UCNews. “We are determined to keep fighting for people in sanctuary. There are four still in North Carolina and over 50 across the country.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Amid detentions and deportations, sanctuary movement persists.”