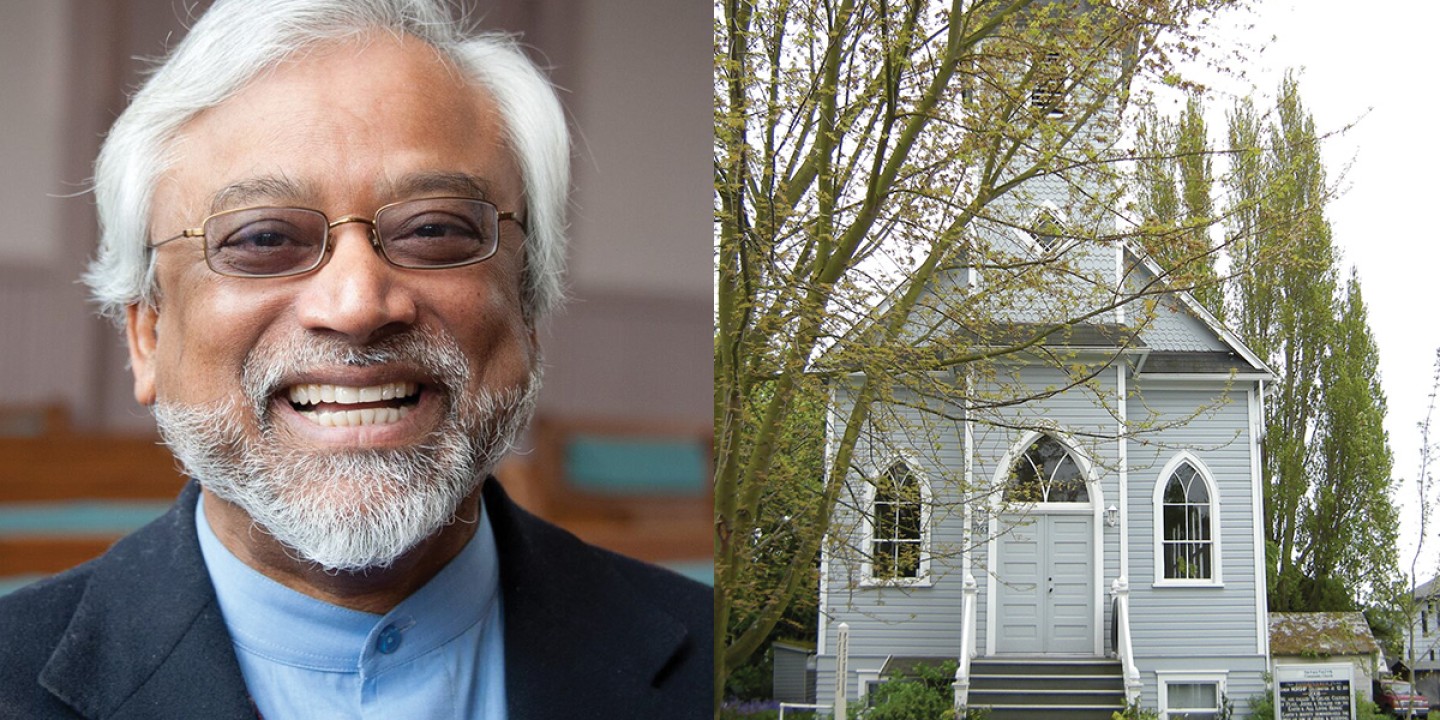

Seattle’s Interfaith Community Sanctuary includes Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus

“People from every religious tradition want to be of service to God’s creation in a genuine way.”

Jamal Rahman is cofounder and Muslim Sufi imam at Interfaith Community Sanctuary in Seattle. He is a popular speaker and author on Islam, Sufi spirituality, and interfaith relations. Interfaith Community Sanctuary won second prize in the 2020 UN World Interfaith Harmony Week Prize from A Common Word.

Tell us about how Interfaith Community Sanctuary became a reality. Where did the idea come from?

In 1992, I was very keen to establish community in Seattle. I left my previous career and began teaching self-development classes. I was trained in Sufism, the mystical side of Islam, so that’s what I taught. I was surprised by how many people came to take the classes.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In seven years we had a few hundred people. From there we started to ask: What does it mean to have an interfaith worship service? We were people of different religions, mostly Christians but also Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus. All of us were looking for a connection to something higher and deeper.

What kind of worship could we do that unites everyone? There are a few things that transcend the boundaries of religion. One is silence. There’s no such thing as a Jewish silence or Islamic silence; it’s just silence. So, we decided, let’s just practice silence in each of our Sunday worship services.

Second, music. Everybody loves music. We had chanters from different traditions, so we added chanting. I would always quote Rumi, “Music is the sound of the spheres. We have been part of this harmony before.” And once we chant and sing and play music, it keeps our remembering fresh and it doesn’t matter what your religion is.

Food is how we came to know the other on a human level. We built that in as well. So we focused on silence, chanting, and food.

Over time, we came to say that we focus on essence, not form. We asked: What is the experience, the taste, we want? We would also say that we wanted to move from a knowledge of the tongue to a knowledge of the heart. That can come from personal relationship, connection, spiritual companions in your life, music, silence, and sharing different spiritual practices.

Every tradition says a person is to become a better human being, a more developed human being. And everyone wants to be of service to God’s creation in a genuine way. Rabindranath Tagore has this wonderful poem: “I slept and dreamed: / Life was joy. / I awoke and found life was service. / I served and lo, service was joy.”

How did you come to be in the church building where you are now?

The oldest church building in King County, Washington, built in 1890, was given to us for free, by the grace of God.

With the strength of the Native American part of our congregation, we came to realize we’ve got to pay rent. So we pay rent to the Duwamish, the Coast Salish tribe on whose land we are.

What kind of people attend Interfaith Community Sanctuary?

We have a variety of congregants. One group is people like me who are rooted in one tradition but open to the beauty and wisdom of other traditions. I always say that this community waters my Islamic roots and makes me a more complete Muslim.

Another kind is the one which is the fastest growing: the spiritual but not religious. The best analogy or metaphor I can think of for them is that of Ramakrishna: they are bees collecting nectar from different flowers.

Then we have people who have what we call multiple belonging. And we have atheists and agnostics among us who might not believe in a religion, but they really want to increase their capacity for being more compassionate, more loving, more forgiving.

How do you see Interfaith Community Sanctuary as a part of the broader religious community?

Sometimes it acts as a channel. Sometimes people don’t stay with us all that long, especially if belief becomes important in their journeys. For example, one woman started as a Christian. She was a nun. She came to us and was very much involved in our congregation. She studied, and she thought she’d become a Muslim, a Sufi. But then she found that her soul was really Jewish intuitively. Sure enough, she loved Judaism and became a scholar of Judaism.

Some people come and then feel they’ve been healed and are able to return to their traditions. For example, we’ve had Catholics who have gotten in touch with the mystical side of Catholicism and returned.

Once we had a program here in the practice of the Dances of Universal Peace. One man learned that he could do the dances every Wednesday at another church. He came to me and said, “Jamal. Thank you so much. I’m so grateful. I found that my path is Dances of Universal Peace.” So he’s happily left us and gone there, but we are so happy that we were able to provide people with that channel.

How has your worship developed over time?

For the last few years, we have had a pattern. The first Sunday of the month, we have a guest speaker. We said that we have to continue to learn about different traditions. Gandhi said that if you really want peace in a multireligious society—not just to talk about it but really to live it—then it is your sacred duty to have an appreciative understanding of the other person’s religion. We take this very seriously, whether it’s a Druid, a Wiccan, a Buddhist, or a die-hard, very conservative Christian, even a Trump supporter. We’ve explored that, and we’ve found we have felt very uncomfortable because most of us are not Trump supporters.

But if we don’t do this, then we are in danger of becoming a private club, of having a holier-than-thou attitude. If you really want peace in a multireligious society, you’ve got to extend yourself outside the tribe.

The second Sunday is what we call universal worship. This is a Sufi practice that was brought to the United States in 1921 by a very well-known Sufi master, Inayat Khan. He said let’s honor all the traditions in a way that’s practical. So in universal worship, we choose a certain number of world traditions. People are assigned to find a short, succinct scriptural saying from that tradition. We ponder that. Every year we have what is called a spiritual discernment theme, so then we use those insights to talk about the spiritual discernment of that particular year. We break into groups and we discuss: What have we learned? How can we apply this in our life?

The third Sunday is my Sunday. I talk about spiritual discernment from an Islamic perspective.

The fourth Sunday is inter-spiritual Sunday, and it is led by my cofounder Karen Lindquist.

Recently, our congregation has requested that we always include some aspect of the divine feminine. The other request is in every service to have something from a Native American tradition—an invocation, a prayer.

What are some of the criticisms that you hear about interfaith community and worship?

It’s always a criticism that interfaith communities are shallow. It’s like digging a well, you can never reach water because they don’t dig deep enough. They just move on to the next one and the next one.

We’ve found that the metaphors you use are very important. What we say is that we are using different instruments to dig the well and reach water.

With the multifaith dimension, we hear the criticism that you should only have one spouse who you love completely. But Ann Holmes Redding, one of our multifaith practitioners, says that her metaphor is like being a mother: you can have more than one child and you can really love them equally.

How do you work with the scriptures from your various traditions?

We say that every holy book has two kinds of verses: particular verses and universal verses. Particular verses are in desperate need of historical and textual content. Universal verses are timeless, placeless, and filled with wisdom.

The danger becomes if you take a particular verse and advocate it as a universal verse. Also dangerous is what you see happening on a lot of anti-Islamic websites, where they will take a particular verse from the Qur’an and compare it with a universal saying from the Bible.

You mentioned service as an important part of life at Interfaith Community Sanctuary. What does that look like?

For the last few years, we’ve had a very strong program with Peace Camp International. We have counselors who come from Uganda and India, from all over. We work with the Parliament of the World’s Religions. And many of the people involved in Peace Camp are involved in orphanages and shelters all over the world, so we’ve become very involved with them as well. Many of the counselors who come to Peace Camp were street children themselves, and we find it very important for our American participants to listen to them. We also are involved in programs in Ethiopia and Bangladesh.

That’s all come from our worship services. Let’s become better human beings. Let’s be of authentic service. Let’s transcend the boundaries of religion, of culture, of political beliefs, and just do the inner, inconvenient work of transforming the ego.

Give us an example of a spiritual practice that is valuable to your community.

One that we are focused on very much is called three cups of tea. This is how we acknowledge differences and come to celebrate them.

What are the three cups of tea? Listen, respect, connect. So first listen. I love Rumi’s definition: true listening is like putting your head on the person’s chest and sinking into the answer.

Number two is respect. Maybe a person’s behavior is unacceptable, but the person behind that behavior has a Christ nature, just as I do. I love that nature. There’s a wonderful Indian mystic named Kabir, a Hindu and Muslim from the 15th century. He says when you meet somebody adversarial, protect yourself, don’t allow yourself to be abused. Take the right action. But as you take the right action, please, do not keep this person’s essence or being out of your heart.

The last one is connect. Share stories. You don’t have to get into a big discussion about Muhammad being the last prophet or Jesus being the only way to God or who the chosen people are. Just connect on a human level.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “An interfaith congregation.”