A stitched-together community

One day Bill didn't show up at the church, so we went to find him.

“How are you related to this man?” the EMT asked me as he put Bill in the back of the ambulance. I climbed in after them. There was no good answer. Friend? Not really. Colleague? Coworker? He was more than an acquaintance. “He . . . we work together,” I finally said.

Bill was the front-walk shoveler, meat-loaf maker, coffee brewer, Saturday night grumpster-in-chief at my church. Every time I arrived at the church, he was busy doing something. He filled the steam-table pans for our community meal. He made sure the stairs were clear of snow. He helped install the handicap ramp. He cleaned the bathroom.

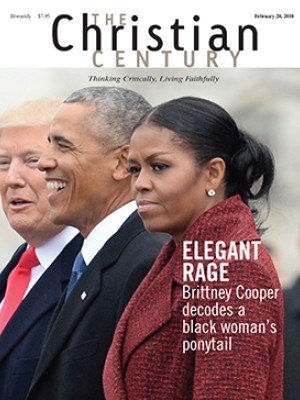

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

He’d arrived in Leadville decades before I had, when he was 19. He had served in Vietnam and planned to use wages earned in the mining industry to fund his addiction to any and every substance. In his forties, he’d settled on alcohol.

Bill was originally from New Jersey, and his speech still had open vowels and wide endings. He told our priest, George, that he had been arrested at 17 for possession of heroin. The police told him he could go to jail or to Vietnam. He chose Vietnam.

An old picture of him from the early 1970s shows him lean and shirtless, gap-toothed and grinning broadly. I had not known this version of Bill. I knew him as the grouchy person everyone in town called “Bottles.” Bill drank, and the alcohol ate away at him. He did not have a home. He slept on various people’s couches throughout town. His routine response to “How’s life?” was “Taking fucking forevah.”

When I first met him, he showed me how to light the stove for the community meal, smelling like stale beer and unwashed clothes. He knew where everything was stored. He complained about everyone and everything—about the people who stood too long next to the coffee machine, who left their cigarette butts on the front porch, who loitered in the hallway, who talked too much, or who were so quiet they must be crazy.

One spring, one of our regular guests at the meal died of liver failure. Kenny’s belly was swollen, and he lost his mind, screaming with terrible tremors, as if accumulated ghosts were tormenting him. He vomited and had diarrhea until he was unable to eat at all. His ordeal went on for weeks, and at last he died.

After that, Bill seemed more withdrawn as he went about his tasks. Then one day, he disappeared. He did not come to the meal. We arrived at church to find the snow had not been shoveled. We didn’t know where he had gone.

After a few days, George could stand it no longer, so he went to look for Bill. He searched every apartment, knocked on every door, until he found Bill, barely conscious in the back of a trailer where he had gone to drink himself to death. As far as I could tell, his reasoning was something like, “I don’t want to die like Kenny. If it is too hard to stop drinking, and liver poisoning is too slow, I am just going to kill myself quickly.”

Bill had been an alcoholic and a drug addict all of his life. He’d left Leadville once and moved to Nevada to work in a mine there. “I did a lot of cocaine in Nevada,” he told me. “I didn’t have a drug of choice. I did anything and everything.”

When he came back to Leadville he worked at the Manhattan Bar. “I actually came up to Leadville to recover,” he said. “When I left New Jersey, I was the second biggest methadone addict in the state. I had a record. The first guy on the list died a week after I saw the list, and that made me the first. I had to get out of there. For me, it was meth. I tried all the drugs, none of them did it for me but meth. Cocaine in them days was crap.

“Then I went to Las Vegas; that’s when I got the cocaine habit. I came up here, and that’s when I started with the alcohol. It was cheaper.”

“I guess wherever you go, drugs are there,” I said.

“Nah,” he said. “The problem with me was wherever I went, I was there.”

George dragged Bill to his car and drove through the night to a Salvation Army rehab center. A week later, Bill was back at church. “They were going to make me cut my damn hair,” he said. “I ain’t doing that.”

But eventually he did go back to the rehab center and stayed. He was gone for almost a year. When he returned, he was tentative in his new sobriety. Eventually, he moved into his own apartment, a one-room place with his own television and a collection of movies. He worked as the church sexton, for which he was paid $500 a month. He carefully meted the money out to pay for rent, cigarettes, and Pepsi.

He no longer carried that stale smell of beer, but in almost all other ways, he was still Bill, irritable and faithful. I don’t know if he would have said he was reborn at our church, or if he was grateful to have been saved from drinking himself to death. I didn’t ask, and he didn’t tell.

If the Spirit was at work in Bill’s life, it never bullied him. It just gently coaxed him, day after day, year after year, using what was best in him, with the rhythms of everyday life. Every time Bill carried the coffeepot to the kitchen and rinsed away yesterday’s grounds to make a fresh pot, and every time he put water in the steam table and put away the mugs left by the AA group (which he did not, would not join), he made a little deposit in the community. And every time we left out a steak for his dinner or got the payroll done on time so he could pay his rent, we made a little deposit in his life. So we each had a kind of bank account to draw on, enhanced, perhaps by grace. And we drew on it to belong to each other and live side by side.

One day in January, I arrived at the community meal to find the snow untracked with Bill’s boot prints. Inside, the coffeepot was cold, the stove unlit. I telephoned our other priest, Ali. “No Bill today. Have you seen him?” Without a phone, Bill had no way of letting us know if he was sick, and in ten years he had so rarely missed a day that we didn’t have a plan for this.

Ali went to Bill’s apartment and knocked. Through the locked door, Bill said he had the flu and was too weak to get to the door but that George had a key. If Ali could get that key, he’d welcome it.

It turned out George did not have the key. Ali sent me over to check on Bill again. I arrived in the near dark, one street light flickering, and followed Ali’s boot marks to the door of Bill’s apartment. He lived in a one-story apartment building with six units, each with its own stoop and entrance. All winter long, Bill had been climbing up on the roof of his building and shoveling the snow off to keep it from melting into the apartments. But recent storms had piled snow heavy on the roof.

I walked up the steps and knocked on the door. “I’m coming,” Bill said. I heard some grunts and moans as if he was trying to get to the door. But they did not sound like they were getting closer.

“Bill, can I call the police to open the door?”

“Yeah.”

When the police, fire department, and ambulance arrived, I knew Bill would think the response was overkill. “Does the man inside need an ambulance?” the young officer had asked me.

“Bill, do you need an ambulance?”

“Nah,” he yelled. “I need Valium.”

The police forced open the door. Bill was on the floor next to his bed on a pile of blankets. One leg stuck out from the blankets, pale and bony. His underwear was hanging off the other leg. As the paramedics wrapped him in a blanket, he said, “That feels good.” He did not know that he’d had a stroke. He’d been on the floor waiting for his strength to come back so he could get to the bathroom.

In the hospital, I sat next to him while we waited for medical transport to take him to Denver. We stared at each other. His eyes were wide and a bright, clear blue. As the IV dripped into his veins, he grew stronger. “Water,” he croaked. And then, “Pepsi.” His mouth was dry and cracked, caked with goop.

“They can’t give you water,” I said. “You can’t swallow it, and it will go into your lungs and give you pneumonia and you’ll die.”

“Bullshit,” he said.

I used lemon-scented swabs to wipe the goop from his mouth. He wanted to suck on them like lollipops.

After a few days in the hospital, the doctors said that serious decisions needed to be made about Bill. But who would help make them? There were no relatives to call. Bill himself was not thinking clearly.

“There is nothing wrong with me,” he told the doctors. “I can go home now.” But when asked to raise his left arm, he raised his right arm, not recognizing that the entire left side of his body had been paralyzed by the stroke.

A small group from the church gathered to meet with the doctors. When we arrived at the hospital, the floor nurse looked annoyed to see us. We learned that the day before two longtime friends of Bill’s had been to see him. He had told them what he told everyone: he wanted to go home. “OK,” a friend named Smitty had said. “Let’s go. Come on, Bottles. Get up and walk. If you can get up, we’ll go.”

After they left, the night nurse tried to put in a feeding tube. The nurses had drugged him and, using X-ray images, were able to get the tube in place. But two hours later, as the drugs wore off, Bill started thrashing and screaming. He tore out his feeding tube, his catheter, and every other line to which he was connected. He had made a bloody mess. The nurse was only now putting things back together. She eyed us as though she feared another episode.

We sat around Bill as we waited for the urologist to come to fix Bill’s catheter. We talked to him through the sedation. “I want to go home,” he said.

“Bill, these machines are keeping you alive. Staying here is keeping you alive.”

There was a pause. Finally, I said, “Bill, do you want to go home to die?”

“No,” he said. “I want a Pepsi.”

As we waited for a doctor to speak with us, there was plenty of time to contemplate the EMT’s question: Who is this man to you? How were we related?

Bill and I shared labor and days. We shared space and coffee mugs. Who is this man to you? He makes coffee for me. Pretty good coffee, too. Somehow, over the space of years, our relation had become a given. The days had been like stitches—some well made, some poorly made—but they had created a mantle that we would now have to assume. I belonged to Bill. Bill belonged to me. And now, I—we—were going to make a decision that only family members typically make. We were going to do this without labels or prescribed roles.

We spent the day contemplating the Bill we had known, who he was, what he loved, and what he wanted from life. As we talked about “our” Bill, we also gradually saw that he belonged to something bigger, something greater than us. We wordlessly came to act as if we knew that he was going into that something, and it was our job to walk him to the door. We did not claim to know what was on the other side. We had no shared language, took no comfort, told ourselves no stories.

One word kept coming up for Bill: home. At first we thought he meant his apartment. We talked about perhaps transporting him there, caring for him there. But gradually, the word took another meaning, one that claimed a place we both knew and did not know. The only way that we could move forward was to believe and to act as if this other place, this home, was love.

We stood around his bed. “The Broncos are going to be in the Super Bowl,” someone in our group said.

“Good,” Bill grunted.

“Bill,” I said. “We are working on bringing you home.”

“Good,” he said again.

We each held his hand. The staff told us later that he was peaceful that night. We started making arrangements with hospice the next morning, but the nurse on duty called early in the afternoon.

“He is leaving fast,” she said. By the time George arrived, he had gone.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Stitched-together community.”