This is my blood, donated for you

When my arm is stretched out and blood is trickling out of me, I find myself thinking of Jesus.

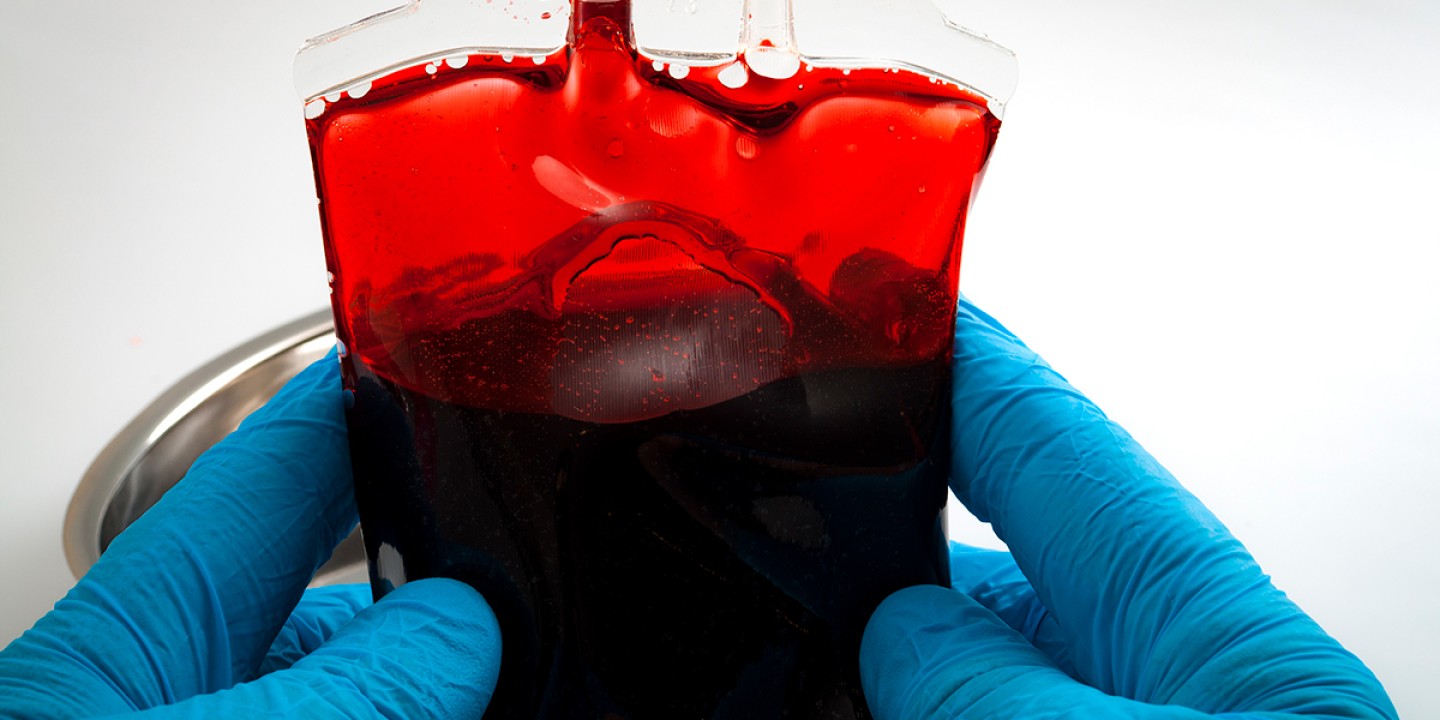

I’m always surprised by how brown blood is, flowing out of my arm through a tube and into a plastic bag at a blood drive. My childhood mind still imagines that blood is always bright red, like cherry tomatoes or strawberry candy, the way it is when it bleeds into the open air. Inside the plastic, it looks brown or maroon, even vaguely purple—my clergy brain can’t help seeing communion wine. But wine is translucent, and the blood in the donor bag is opaque, creamy with iron and protein.

It is somewhat nauseating to feel and watch your blood dribble out of your arm, even inside plastic tubing. It hurts to have a needle stuck in your arm, and it’s unnerving to squeeze your hand to speed the flow of blood out of your body. Giving blood is painful, dull, and clinical, but it has come to feel like a spiritual discipline in my life, a kind of ascetic practice. Not as a penance or purification, but as an offering.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It’s not dangerous to give blood, but you may pass out or throw up. A staff person is continually asking: “How are you feeling? Are you doing OK?” If you’re not, they’ll recline your seat, elevate your feet, and put a wet cloth on your head. I’ve gotten woozy a couple of times, and once both my arms went numb. I’ve learned to drink a full bottle of water during the intake process, to plump my body with hydration.

The pain of giving blood starts the moment you sit down for your intake interview. The phlebotomist asks to prick the end of your finger in order to smear your blood on a slide to insert into a machine that tests your iron level. If your iron is too low, you go home. Next, you have to display the naked undersides of your arms all the way up to your elbows. They don’t say so, but you are being examined for needle tracks.

If your iron levels are sufficient and your arms free of signs of intravenous drug use, the phlebotomist moves to a series of discomfiting and intimate questions. You are asked, bluntly and without charm, about who you have sex with, your experience with illegal drugs, whether you’ve ever been pregnant and how many times, what medications you take, whether you’ve had anything containing aspirin in the past three days, what medical transplants or grafts you’ve had, whether you’ve traveled outside the United States in the last three months and to where, whether you’ve traveled outside the United States in the past three years and to where. You are asked almost exactly the same blush-inducing and sometimes head-scratching questions (wait, have I taken aspirin in the last day or two? when did we go on vacation again?) every single time you come to donate. Qualifying to give blood can feel like a test of worthiness.

While most of the questions are medically important, some are discriminatory. A man who has had sex with another man within the past 12 months is categorically not allowed to donate, even if he has been married and monogamous for decades. This is actually a recent improvement: before 2016, having had sex with another man at any point in the past would have gotten him permanently banned from donating blood.

If you pass all these tests, you are invited to take a seat on an exam table. The phlebotomist swabs your skin with sanitizer and then inserts a needle deep in your arm. You flinch, then you bleed and wait.

This is when I find myself thinking about Jesus, since my arm is stretched out and blood is trickling out of me. I also can’t help but see something most Christians, including me, don’t even believe in anymore: the mortification of the flesh, the shedding of blood as a spiritual sacrifice. What the heck? It’s hard for me to imagine this doesn’t happen to other Christians, too, when they give blood.

The only sermon I’ve ever heard that was specifically about Jesus’ blood was in seminary. The preacher showed us the image of a mother pelican feeding her young by plucking her breast to shed her own blood—a symbol of Christ. Then she showed us a medieval painting of Jesus on the cross, his blood spurting in an arc from the wound in his side like water from a drinking fountain into a chalice held by a cherub. To us it was gory and strange, but that was the point she was trying to make to us, a congregation of mostly White, Protestant master of divinity students. She proclaimed to us that the blood of Jesus—human blood—is a part of our Christian spiritual inheritance.

I can’t recall if she told us how we might claim that inheritance, or what this might mean in the world outside the chapel. But the gory, incarnate love of those images—the breast-biting pelican and Jesus as a blood-dribbling drinking fountain—was vivid.

I grew up in an intellectual congregation within spitting distance of that same divinity school. The worship and theology were poetic and beautiful, rational and academic. We didn’t talk about the crucifixion much, or even Jesus, for that matter. So I distinctly remember the time in Sunday school when our teacher, a conservative in the minority at our liberal congregation, taught us that “Jesus died for your sins” and “his blood paid the price.” I had never heard language like this before, and I didn’t quite understand what it meant.

I loved my Protestant church and the transcendent mystery I felt there, but I also loved making the sign of the cross at my Catholic elementary school, kneeling to pray, and touching the holy water in the stoops by the doorways. I couldn’t take communion with my classmates, but my body was involved in worship and the life of faith there in a way that I didn’t experience at my home church. The body of Jesus on the cross was front and center, too, with nails, wounds, and all, which made me squirm. Nonetheless, just like at my church, we didn’t talk much about the crucifixion or blood—and definitely not the mortification of the flesh—at my post–Vatican II Catholic schools, either.

But even if you never talk about it, it’s hard to avoid blood in church. Once a month on Communion Sunday, my childhood pastor held up a pitcher of grape juice and repeated Jesus’ words: “This is my blood.” Blood comes up in scripture readings, psalms, and hymns. I remember hearing in Sunday school about the blood of Abel crying out from the ground and the Israelites smearing blood on doorposts at Passover. I can’t blame the adults who formed me in the faith in the 1980s and ’90s for not wanting to talk to kids about cutting the throats of animals for temple sacrifice, about Jesus’ gruesome execution, or about what the heck Jesus meant when he invited us to drink his blood and eat his body.

It was in a college class that I learned that in the Hebrew Scriptures the meaning of blood is intertwined with life force, in Hebrew nephesh, meaning soul, self, life, and, rather graphically, throat—what you cut to sacrifice an animal’s life. It’s a word that is intimately associated with the body, unlike the English word soul, which connotes something floating above the body or in another realm entirely. Nephesh is the energy of life in your body and blood, what makes you alive, and what makes you you. It is the word for soul in the commandment, “You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” (Deut. 6:5). It is the word for life in a Levitical text forbidding the eating of blood: “For the life of the flesh is in the blood” (Lev. 17:11).

Blood, nowadays, is not very sacred or spiritual. It is mostly clinical or disgusting. Also scarce: maybe we see a few drops when we get a cut or scrape, in a nosebleed, or when we unwrap a raw steak. About a quarter of human beings get a monthly menstrual period, but that blood is hidden from view, collected, and disposed of. We may imagine blood is abundant in hospitals, but unless we’re medical staff, we probably don’t see much even there.

On the other hand, blood is used generously for its shock value in movies, video games, and contemporary art. Fake blood is sold in capsules, tubes, bottles, and half-gallon jugs for use on Halloween. For most Westerners, blood does not suggest the soul, life force, or selfhood; it’s just gross.

But for all the wonders of modern medicine, there is still no replacement for human blood. There is no synthetic version, engineered serum, or animal blood that can do the trick; it has to come from the arm of a human being. If one person is running out of blood, another person has to sacrifice some of theirs to keep them alive. It’s a zero-sum game. Donating blood is not life-threatening, but it’s not insignificant either: a pint of blood takes the body six to eight weeks to replace. It’s just two cups—16 ounces. But it feels substantial when you see it in a bag, and when the phlebotomist picks it up and it sloshes in their hands. It’s as big and as small as a container of sour cream, a grande latte at Starbucks, or a squeeze bottle of ketchup at a diner.

Each time I subject myself to the awkward mortification of donating blood, I feel like I am claiming a part of my Christian inheritance. If it wasn’t so sanitary and banal, it would look medieval. It’s nothing like Christ’s Passion, but it’s no feel-good experience either. The process is painful and clumsy; it involves bureaucracy, prejudice, and needle pricks. Donor banks don’t try to make it uplifting, although they do always say, “Thank you so much for coming in today” at the end.

Maybe giving blood is as close as we moderns can get to an ascetic spiritual discipline. And yet, it’s not like any other spiritual discipline I know—because it’s helping to save someone else’s life.

I feel close to Jesus in the physical experience of being wounded out of a desire to help others, not that I am being crucified in any sense or that my blood atones for anything. But for just a few minutes I am a little bit like him, a pelican plucking the blood from my body (with help from a phlebotomist) to feed someone else.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Donated for you.”