Two stories that define our world

One tells us we can have anything we want. The other says our problems are someone else's fault.

These are strange times. I’m finding it hard to know what to hope for and what to pray for. My sense is that we are living amid two overlapping stories.

The first is the freedom story: Once upon a time we lived in a class-ridden, race-dominated, and gender-constrained society. But gradually the inhibitions of power, privilege, and prejudice began to be dismantled. The three key agents in this transformation were technology, globalization, and finance.

What does Christianity mean in this story? Its so-called liberal wing has tended to point out the casualties of the freedom story, to which the answer has tended to be that they simply need a larger dose of freedom. Its so-called conservative wing has tended to highlight those things the freedom story doesn’t satisfactorily address, notably sin and salvation. But the logic of the freedom story is so expansive and undaunted that it somehow assumes that through technology, globalization, and finance it will surely get to even those things someday.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

That freedom story—the West’s prevailing story in my lifetime—has recently been dealt two body blows. The social aspect of the freedom story, by which it is assumed that the dismantling of all arbitrary barriers would unleash creativity, energy, and peaceful co-flourishing, was symbolically disfigured on 9/11 with the eruption onto the global stage of a ruthless, uncompromising, fanatical rejection of almost everything the freedom story stands for.

Then in the 2008 global crash the economic aspect of the story was fatally damaged. Finance turned from a mechanism for promoting the public good to a venal indulgence that poisoned the public water. Globalization, it turned out, could disseminate viruses just as quickly as it spread blessings. And technology that had promised to unlock and empower suddenly seemed to be equally capable of impoverishing and marginalizing, outsourcing and making redundant.

The second story is based partly on suspicion of the first. It’s the slavery story: Once there were stable communities where people earned a decent living. They had family living close by. They could expect to work in the same line of business all their life, buy and embellish their own home, and enjoy a few years of respectable retirement. Free education meant that if their children did well they could make a better life for themselves, near or far.

But one way or another, the building blocks of this stable life have been undermined and its more modest freedoms taken away. And when some higher-up person in Washington tells you things are flourishing and all is well, you realize that either they’re living in a different country or you’ve become their slave.

This mix of profound inequality and simmering distrust creates fertile soil for ideologies of hate that assign blame for the slavery story. But the slavery story also identifies an important truth: that the great liberating forces of technology, globalization, and high finance have paradoxically made slaves of us all.

For Christianity, there’s a sense of “I told you so” when it becomes clear that the freedom story is flawed and its benefits are unevenly distributed. But the anger, division, and hatred unleashed by the wilder reaches of the slavery story are troubling—and few Christians are comfortable being identified with a worldview that can speak only of negativity and loss.

I think the reason the present time is so confusing is that we are recognizing the flaws in the freedom story, yet we are incapable of letting it go because so much of our identities, livelihoods, and assumptions are tied up with it. Meanwhile, we accept that a great deal of the slavery story is true. But once it gets beyond protest, its implications seem so lacking in hope—and its more extreme advocates are often so unappealing, even horrifying.

For the New Testament, the ideal of absolute freedom from all constraint is a fantasy. The question isn’t whether outside forces have power over us. It’s this: Are we going to allow ourselves to be possessed by pernicious and deceitful powers? Or will we discipline ourselves through obedience and thus allow ourselves to be owned by the truly liberating spirit of grace? In other words, we’re all part of a story that’s bigger than us, like it or not.

Both the freedom story and the slavery story are ultimately false stories. One says that, left to ourselves, we will get beyond the story and realize all our dreams; the other says that every story is really a conspiracy story and all our troubles are someone else’s fault. Neither offers a genuine vision of hope, inspiration, or longing; both are about identifying and overcoming obstacles rather than describing where we’re going.

To navigate these bewildering times, we need a renewed story. Christianity is fundamentally a story about where we’re going: into the company of God’s grace, in the harmony of the restored creation, through the mercy of God’s incarnate love. To honor that story means to practice disciplines and foster habits that evoke its meaning. Church means giving up the fantasy that we can find fulfillment and righteousness alone. It means doing things at inconvenient times with eccentric people in sometimes clumsy ways—because life is a team game, and on judgment day God will have nothing to say to us if we think we can come without the others.

This is not a time to despair. We’re possessed by one who wants only good for us, who in Christ has shown us the cost and extent of that grace—and took on our slavery that we might find true freedom.

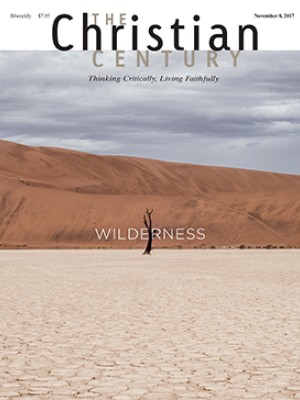

A version of this article appears in the November 8 print edition under the title “The world’s two stories.”