Dutch election highlights divisions about religion and immigration

Dutch Muslims are breathing a sigh of relief after the worse-than-expected performance by anti-Islam populist Geert Wilders in the mid-March election.

“We have trust in the future” of this traditionally welcoming country, said Rasit Bal of the Muslim government contact organization, an advocacy group for Muslims in the Netherlands, which feared that a victory by Wilders’s PVV party would strengthen anti-immigrant sentiment in the Netherlands.

Gerard de Korte, bishop of s’Hertogenbosch, said the outcome shows that Dutch voters rejected Wilders’s extreme rhetoric, which included calls to close mosques and ban the Qur’an.

“From the view of Catholic teaching, that is positive,” he said. “His position is dangerous.”

At the same time, de Korte advocates paying attention to the questions that Wilders supporters ask: “For the other parties it is very important to take the questions of the voters seriously but give better answers, more in line with Christian social teaching. It is important for polarization to stop now.”

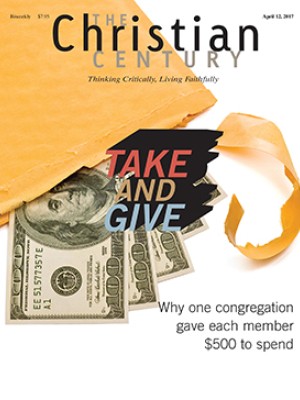

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Wilders, who has been labeled the “Dutch Trump,” had called for sealing off the border to Muslim immigrants and making “the Netherlands great again.”

“All the values Europe stands for—freedom, democracy, human rights—are incompatible with Islam,” Wilders said in a 2015 video addressed to Turkish immigrants.

Despite the result for Wilders, his PVV party still increased its share of the vote to become the second-largest party in parliament, leaving many worried about its influence. Since the mainstream parties have vowed to exclude Wilders from any ruling coalition, the PVV, which stands for the Party for Freedom, could become the key opposition force.

Binyomin Jacobs, president of the Rabbinical Council for the Netherlands and a representative of the country’s small Jewish population, said parts of Wilders’s main message were echoed in more moderate terms by the main parties, which took a harder line than usual on integration and immigration. So he still wonders: “What direction will the large majority go?”

On March 14, the day before the Dutch election, the Court of Justice of the European Union, which interprets EU law, issued a landmark judgment that upheld the right of private companies in EU member countries to enact policies barring employees from wearing “religious, political and philosophical signs” in the interest of “neutrality.”

Such visible signs range from Jewish kippahs to Sikh turbans and Hindu bindis; Christian crosses can perhaps remain hidden under clothing.

The court decision was a response to two legal cases, one from Belgium and the other in France, in which a Muslim woman was dismissed by her employer because of her headscarf.

In the Netherlands, Muslims make up approximately 6 percent of the total population of 17 million. Bal’s organization, which runs government-mandated Islamic education classes for Muslim children in public schools, encourages debate and discussion about cultural integration, especially among the offspring of immigrants.

“Their future is here,” he said. “The main challenge is how to connect this new generation to Dutch culture.”

But the challenge will also be to keep them tethered to their faith.

Berksun Cicek is of Turkish descent but no longer practices the Muslim faith. She is involved in an organization for LGBT Muslims and was surprised by the PVV’s strong showing in her hometown, Rotterdam, a working-class port city with many immigrants and a Muslim mayor.

“The patience is decreasing on both sides” of the political spectrum, she said. “I hope for the best.”

Klaas van der Kamp, secretary-general of the Council of Churches in the Netherlands, believes religion should be a unifying factor in the country, which has a long history of ecumenical cooperation among disparate confessions.

“The church is one of the few organizations in society that has members in all areas of society,” he said.

But he said a vacuum has been left by the decline in religious engagement.

Bishop de Korte feels the same way. And he said Wilders played into insecurities of a cross section of Dutch people.

“A lot of people are insecure—also a lot of Christians,” he said. “But I think there is a difference between people who are baptized and people who are going to church. A lot of Christians have also voted for the PVV, I think. But what I see is that people in the parishes and in the Protestant communities who are active in the church, there the PVV are only a small minority.” —Religion News Service

A version of this article, which was edited on March 27, appears in the April 12 print edition under the title “Dutch election highlights divisions about religion and immigration.”