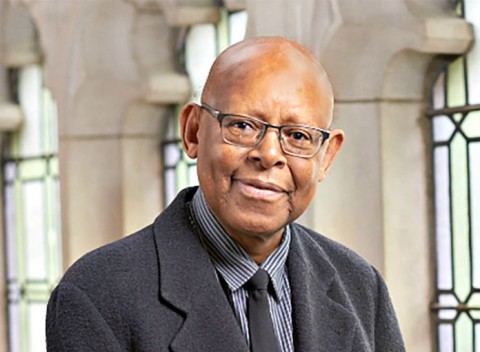

James Cone looked evil in the face and refused to let it crush his hope

Antiblackness is outrageous, but it does not have the last word.

In college I wrote a paper on the work of James Cone in which I barely grasped the profoundness of his thought. My religion professor did not hesitate to tell me so.

Later, as a student at the University of Chicago Divinity School, I was among a small group of students keen to invite Cone to lecture at the school. Our idea was met with the response that “identity politics are passé.” It turns out I was not alone in failing to fully grasp the black power of James Cone. At almost every turn in his professional career, he was met with misunderstanding, disregard, suspicion, and outright dismissal. The persistent rejection is no doubt a testimony to Cone’s persistent truth telling about racism.

Cone’s work—including Black Theology and Black Power (1969), A Black Theology of Liberation (1970), and The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011)— illuminates like no other the entanglement of race and religion. Blackness in America is about God in America. Cone identified black power as a religious concept and racialized oppression as a thoroughgoing theological crisis at the heart of the Christian message. God is black, and to be black like God is a gift.

Cone perceived with utmost clarity the God revealed in the black experience. Unconcerned with any metaphysical conundrum of the Christ event, Cone focused attention on divine justice in which divine wrath and divine love are not at odds with each other. He captured the subversive element in Christian thought that perceives love as violence against the status quo of white supremacy. Cone sees what he calls “the terrible beauty of the cross.”

Cone defied the activist-scholar and church-academy dichotomies. For him, being a lover of the gospel is synonymous with being a freedom fighter. When done properly, theology is itself activist. Theology is a protest movement, and when it fails to contribute to social change it is complicit in the normalization of violence and colorblind ideologies that become the gateway to genocide.

Black theology is not a metaphor for politically correct curricula based on a couple of books considered provocative in light of the political context of the 1960s, intriguing in its rhetorical flourish but not substantively compelling—except insofar as it is commodified in the academic marketplace. Black theology is not a metaphor for ghetto theology. Black theology is a critical theological lens through which to view black life and black death.

Debates about Cone’s work often grapple with his relationship to the work of Karl Barth. Cone never set out to baptize Barth in liberation theology, and neither did he engage in the foundationalist need to legitimize liberation theology with orthodoxy. Cone’s reading of the gospel was always distinctly his own. More to the point, Cone never wavered in his commitment to divine freedom. What is at stake is not his relation to Barth but his commitment to the message that God sets the black captives free.

Rereading Christianity through the lens of blackness and freedom makes Christianity more Christian because it is more free, more radically theological. Black subjectivity, as Victor Anderson once argued, is not reducible to ontological blackness, where blackness stands for suffering and resistance. Cone’s black subjectivity is grounded on freedom and hope. Cone’s freedom is not Barthian, it is black. In 1981 he wrote in the Christian Century:

My black colleagues in the National Conference of Black Churchmen and the Society for the Study of Black Religion helped me to realize more clearly that theology is not black merely because of its identification with a general concept of freedom. It is necessary for the language of theology to be derived from the history and culture of black people. The issue is whether black history and culture have anything unique to contribute to the meaning of theology.

Ever avoiding facile oscillation between black suffering and hope, or slippage into glib notions of redemptive suffering or talk of theodicy, Cone offers no justification of God in the face of black suffering. Cone’s indictment is not against God but against the racist and antiblack forms of Christianity. Cone looks evil in the face, seeing with eyes wide open the grotesque in recrucified black bodies hanging from poplar trees, locked in cages by the “justice” system, and lying dead in the streets. Yet still Cone rejects the nihilism of Afropessimism.

This is another mark of the profoundness of his theology—his ability to hold together the everyday lived experience of antiblack oppression without explaining it away by appeals to divine mystery, without preaching an otherworldly future, and without resorting to resignation or despair. “Anybody who loses hope and gives up in despair—they die.” No redemptive suffering here. “Suffering is not the means for heavenly entrance.” He rejects all appeals to divine inscrutability. Instead he speaks of hope in the here and now. “Black theology has hope for this life. The appeal to the next life is a lack of hope.” Hope is not a theoretical concept but a practical idea that deals with the reality of this world. More than that, hope is rebellion against injustice.

“Black power is an expression of hope, hope in the humanity of black people; it speaks to God’s intention for humanity,” Cone contends. Perhaps he knew just what Alice Walker meant when she wrote that womanism “loves struggle.”

The womanist critique of black theology for its failure to account for black women’s experience led to Cone’s self-criticism as early as 1981 and which he continued to address in his writings. “My earlier books ignored the issue of sexism; I believe now that such an exclusion was and is a gross distortion of the theological meaning of the Christian faith.” The womanist critique was itself a sign of the fecundity of Cone’s thought. Black theology’s patriarchal blind spots made way for the inbreaking of a new discipline attentive not merely to race but to class, sex, and gender as theological problems.

Cone generated a paradigm shift in Christian theological discourse. Theologians will no longer be able to responsibly engage in their work without recognizing the social and political dimensions of their projects. Theology is irrelevant when it is morally detached and relevant only when its aims are connected to transfiguration of the world in the name of human freedom.

In a 2017 lecture at Yale Divinity School, Cone repeated the names of black children recently lynched at the hands of police. His litany, “a cry of black blood,” was all the more poignant as it was breathed into the air of the chapel, as if speaking to ivory towers everywhere the very words he wrote in 1969: “The passive acceptance of injustice is not the way of human beings.”

I will always remember his unapologetic conviction, his relentless hold on the gospel, his subjective certainty of black subjectivity so utterly unyielding that it was too often mistaken as dogmatic self-righteousness. Many a student and reader has characterized Cone as angry, but Cone never participated in the politics of outrage designed to produce moral capital. Cone was not outraged for the sake of street cred. Cone put theological legs on outrage. Antiblackness is outrageous, but it does not have the last word.

To the Rev. Dr. James Hal Cone, who birthed and breathed black liberation theology, I give the last word: “The willingness of black people to die is not despair, it is hope, [hope] in their own dignity grounded in God himself. This willingness to die for human dignity is not novel. Indeed it stands at the heart of Christianity.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “God revealed in blackness.”