Howard Thurman’s contemplative nonviolence

The pastor and mentor to Martin Luther King formed a vision of resistance around prayer, not politics.

Revered by the leaders of the civil rights movement for his mysticism, not his activism, and for his pastoral presence, not his political strategy, theologian Howard Thurman is to many people a somewhat perplexing figure in American religious life. A man committed above all to prayer and spiritual discipline, he was a key inspirational figure for Martin Luther King Jr. Thurman has recently been introduced to a new generation through the film Backs against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story, produced by Martin Doblmeier and Journey Films. (The film, which has been aired on PBS, won a regional Emmy award for best historical documentary.)

As the film recounts, Thurman was born in 1899 and grew up in deeply segregated Daytona, Florida. His grandparents, who had been slaves on a Florida plantation, introduced him to the Christian faith and enabled him to attend one of three high schools for African Americans in all of Florida. Ordained as a Baptist minister, he attended Rochester Theological Seminary and was a pastor for five years before becoming a teacher of religion and philosophy at Morehouse College and Spelman College in Atlanta. In 1932 he became dean of the chapel at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In his biography, With Head and Heart, Thurman describes the structures of racism and his personal encounter with them, from Florida to Atlanta and from Atlanta to Washington, D.C. In those days, Jim Crow laws were in full force. It was the era of lynchings and a resurgent Ku Klux Klan.

By the early 1930s, Thurman was pondering how to address racism not through policy or protest but through the transformation of the soul. In 1936 he was part of an American delegation to India organized by the Student Christian Movement. The trip included a meeting with Mahatma Gandhi, a meeting that ended up changing Thurman’s life and altering the trajectory of American religion and politics.

At the time, Gandhi was at the forefront of Indians’ resistance to British colonial rule. But Thurman resonated more with the mystical center of Gandhi’s thought than with its tactical application. Thurman saw in Gandhi a person who embodied the moral courage and contemplative orientation that was needed for spiritually addressing racism and violence. (The history of this encounter has been recounted by Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt in Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence and by Sarah Azaransky in This Worldwide Struggle: Religion and the International Roots of the Civil Rights Movement.)

Thurman left Howard University in 1944 to put this vision into practice in the life of a congregation. He was cofounder of one of the first intentionally interracial congregations in the country, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples. This interfaith community in San Francisco was devoted to “personal empowerment and social transformation through an ever deepening relationship with the Spirit of God in All Life.”

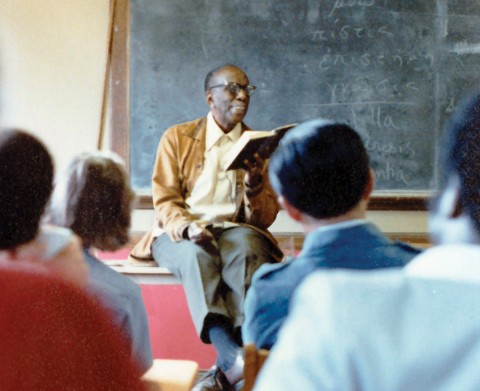

After spending nine years at the congregation, Howard returned to academia, this time as the dean of the chapel at Boston University. It was there that he encountered King as a young doctoral student. It was under Thurman’s tutelage that King first began to see nonviolence not simply as a political tactic but as part of the life of contemplation and prayer.

Thurman begins his best-known work, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949), with a statement that would be echoed decades later by black and liberation theologians:

The significance of the religion of Jesus to people who stand with their backs against the wall has always seemed to me to be crucial. It is one emphasis which has been lacking—except where it has been a part of a very unfortunate corruption of the missionary impulse, which is, in a sense, the very heartbeat of the Christian religion. . . . Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, religion and national origin?

As Thurman’s book unfolds, however, it focuses not on black people’s political disenfranchisement but on Jesus’ call to his disciples to embrace one’s enemy and reject the way of violence. In chapters overflowing with the rhetorical skill of a preacher, Thurman describes how those with their backs against the wall are tempted to give in to fear and deception, and he argues that Jesus of Nazareth lived in that same kind of situation.

Jesus’ commendation of truth and love, says Thurman, came out of his own identification with those who suffer. Jesus was not removed from the scene of violence, but he nevertheless taught that the hatred of the bigot is not to be returned with hatred and that the lies of the powerful are not to be met with further deceptions. It is those who have their backs against the wall—those with whom Jesus has identified—who can show the world the way out of violence.

A nonviolent approach to racism and violence is possible, Thurman believed, only on the basis of a transformative encounter with God. Only in that encounter does the soul open itself to a new way of living. In the mystical encounter of prayer, not only do people transcend the doctrinal particularities which divide Christians and divide one faith’s claims about the nature of God from another; in prayer people are driven to confront the core issue of violence—the self-righteous and egoistic self. The ego is thereby displaced from its throne, replaced by the desire for union with the beauty of God. Our false selves are undone, and we realize the dignity of every person.

These themes were echoed in King’s own work, especially when he emphasized the dignity of both black people and their white oppressors. Thurman’s teaching shaped King’s belief that conflict can be resolved only through the love of God, not by more conflict. Both political and interpersonal conflicts, Thurman wrote, are self-perpetuating. The wounded end up wounding others, creating an endless desire for revenge. The mystical encounter with God, by contrast, replaces our self-righteous need for vindication with a desire for union.

The contemplative encounter with God in prayer as described by Thurman does not immediately translate into a political program. Thurman’s neglect of politics was puzzling even to those who greatly admired him, such as activists Vernon Jordan and John Lewis, both of whom offer their reflections for Doblmeier’s film. Otis Moss Jr. notes in the film that Thurman offered “the basis for the march” and wonders why Thurman did not himself take up the march for justice. Thurman was always a man of the chapel and the classroom, and his role in the civil rights movement was that of inspirational figure. The activists remember that King kept a copy of Jesus and the Disinherited with him much of the time.

What can we make of Thurman today? Can the man whom Lewis called “the saint” of the civil rights movement speak to current forms of institutionalized racism or to an era that has witnessed the rise of a reinvigorated white nationalism? Or more acutely, what does an approach of prayer offer that more familiar approaches to social problems—such as protests and policy—cannot?

Perhaps a clue can be derived from a lesser-documented element of the civil rights movement. Historian Stephen Haynes has detailed how interracial groups of students introduced a new form of protest in 1964 when they started kneeling in prayer in front of Presbyterian churches in Memphis to protest those churches’ segregationist policies. This public liturgical action—the kneeling posture of prayer—constituted an ecumenical demonstration of divine judgment on unjust social structures. (See Haynes’s The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation.) Performing this liturgical act in a public setting was a way of expressing the universality of God.

An action in that tradition was taken last year in Pittsburgh in the wake of the shootings at the Tree of Life Congregation. Among the groups gathered to mourn the deaths and speak out against anti-Semitism was the Jewish advocacy organization IfNotNow. The organization offered people the opportunity to sit shiva—to mourn for those murdered at the synagogue and for other victims of white nationalism. Shiva is a period of mourning in the Jewish faith, and a family typically sits shiva at home for several days to grieve for a relative after he or she has died. Singing the mourner’s Kaddish and praying “Blessed is the Lord, Master of the universe, the True Judge,” the crowd—comprised of Jews and non-Jews—offered their public prayers as a condemnation of the violence that had taken place.

These gestures at least suggest what activism joined to prayer might look like. Yet it is unclear exactly what Thurman would have made of these events. Prayer-as-protest stretches the bounds of the quiet and contemplative approach he spent his life enacting and advocating for.

In any case, such clear and powerful public prayers—whether expressing lament or the judgment of God—cannot be done, Thurman believed, apart from the slow work of the contemplative life. In this respect, Thurman belongs in the company of contemplatives like Thomas Merton, Henri Nouwen, and Dorothee Sölle.

Thurman presents a twofold challenge: those who would be contemplative must identify with those who are suffering, and those who would address suffering must be contemplative. To know the God who joins with the oppressed, with those whose “backs are against the wall,” is to submit oneself to that God in prayer. In doing so, our transformation goes all the way down to our bones; we become people who can embody the way of Jesus, chastened in prayers and quieted in our anger, steeled with a moral courage that no violence can efface.

The challenge of following in the wake of someone like Thurman is that every attempt to turn his work into a tactic is a kind of betrayal of his work. His response to racism was not to seek a new policy but to construct a congregational alternative to segregated Christian denominations. In an increasingly post-Christian America, proposing prayer and congregational life for deep-seated issues such as structural racism and violence seems counterintuitive, but only because we are used to seeking policy before personal transformation. For Thurman, policy was unthinkable without the deeper work of contemplative transformation.

As a white theologian and ethicist, it is not for me to evaluate Thurman’s legacy for black Americans. But as one who wants to join Jesus alongside those with their backs against the wall, Thurman inspires me to pursue my own journey of purification: to recognize the ways in which racism and violence remain a part of my life and to be subject to a God who calls for a change of vision that goes all the way down. In prayer, perhaps, I will be able to be silent and listen, and be led by God and my backs-against-the-wall neighbors.

A version of this article appears in the the print edition under the title “Prayerful resistance.”