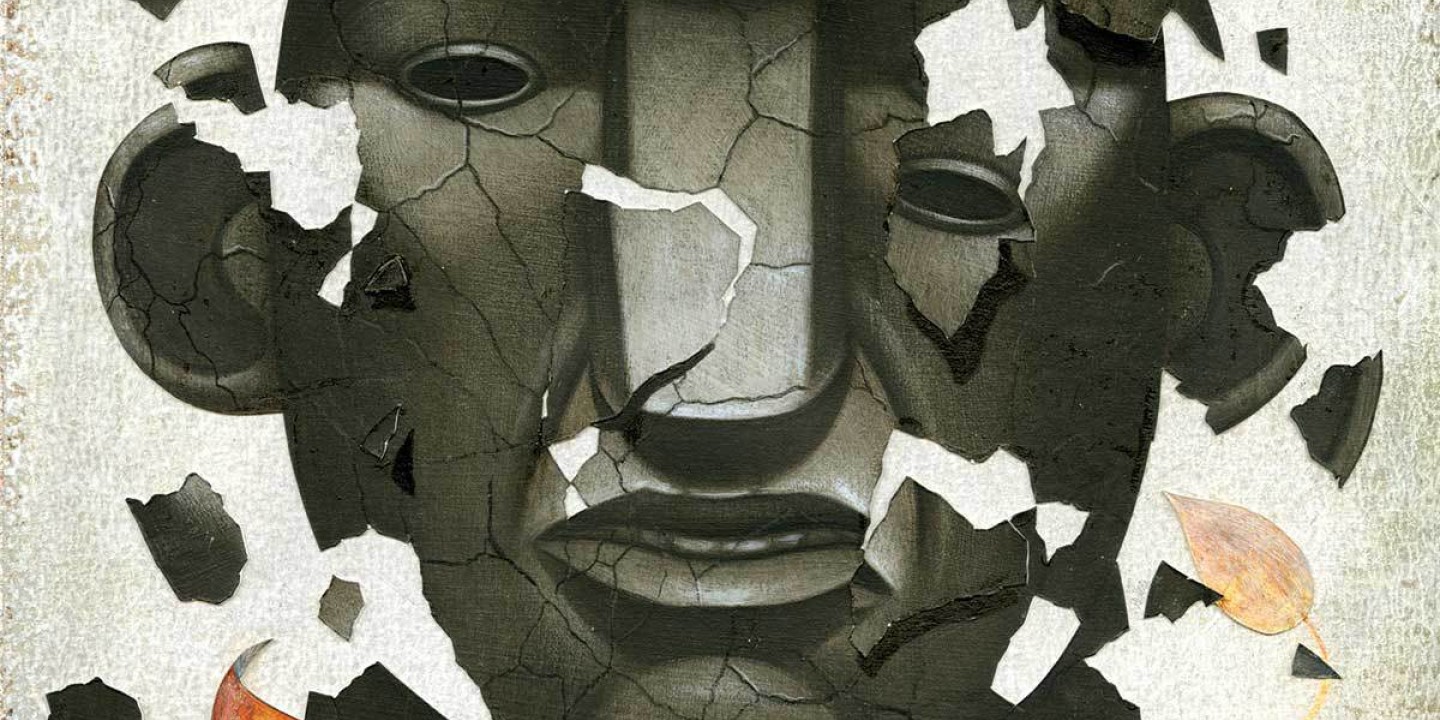

How Christian theology and practice are being shaped by trauma studies

Talking about God in the face of wounds that won’t go away

Psychological trauma is not a new phenomenon, but it is newly studied. Flagged by pioneering psychoanalysts at the end of the 19th century as a wound of the psyche, the term trauma is a modern way of describing how violence impacts us psychologically and emotionally. Sigmund Freud noted that veterans of World War I did not simply recall the violence they had endured in the war but were reliving it in the present. That observation defied existing theories of time and experience. The veterans’ failure to delineate between then and now signaled to early theorists of trauma that the timeline of how we interpret experiences is profoundly shattered in cases of overwhelming violence.

In 1983, the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) entered the psychiatric diagnostic manual. Judith Herman’s 1992 book Trauma and Recovery brought trauma to further public attention by noting the similarities between the experiences of combat veterans and those of sexual abuse survivors. Studies of second-generation Holocaust survivors inaugurated collaborative work across disciplines and generated what is now referred to as trauma theory. These works widened the scope of study from an exclusively psychological framework to literary, historical, and philosophical accounts of experience, and they moved from the interpersonal to the collective realm. For example, Toni Morrison in her novel Beloved provides a specter of the unaddressed trauma of chattel slavery in the figure of a dead child whose ghost returns to tell truths about the past. Morrison understood that cycles of violence play out across generations. The wounds do not simply go away.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Experiences of pain, loss, and suffering are part of human experience, and in time many are able to integrate the suffering into their lives. But trauma refers to an experience in which the process of integration becomes stuck. Pastoral theologian Carrie Doehring identifies trauma as “a bio-psycho-spiritual response to overwhelming life events.” In traumatic response, there is a breakdown of multiple systems that we rely on to protect us from harm and to process harm. In these cases, our systems are not simply slow to integrate the impact; they fail to integrate it. Trauma marks a “new normal” in that there is no possibility of the person returning to who they were before. A radical break has occurred between the old self and the new one.

The therapeutic challenge facing someone who has experienced trauma remains that of integrating the experience into their life. This entails working through the obstacles of ruptured memory, the inability to narrate the experience, and the shattering of assumptions and relational bonds that once sustained life. The processing of memory into language is a function of the frontal lobe of the brain, and much therapeutic work focuses on telling the story of one’s trauma. Talk therapies have dominated the field.

But research suggests that talk alone is insufficient. Those attuned to neurobiology emphasize that traumatic memories are stored as body memories in the limbic system. In traumatic recall, bodily sensations mobilize to respond to danger, even if the context is not threatening. This is what is known as being “triggered.” If trauma is stored as sensations in the body, then the focus of therapy must be on retraining the body to respond without registering constant threat. Practitioners focus on breath regulation and mindful body movements that restore a sense of safety.

The study of trauma and the rise of trauma studies have had a necessary impact on Christian theology. They have exposed glaring limitations in some Christian accounts of suffering and turned theologians in new interpretive directions.

Whereas Christian theology often approaches the topic of suffering through the classic framework of theodicy—making sense of evil within God’s rule of the world—trauma theologians question this framework on pastoral grounds. Aiming to reconcile what we know of God’s nature with what we know of evil and suffering in the world, theodicy frames suffering as an abstract problem to be solved. This approach can hover above the realities of what someone is experiencing. Rather than trying to offer an explanation of what is taking place, theology needs to witness to what is taking place. This approach mirrors some of the critiques of talk therapy: theodicy is the work of theology’s frontal lobe; theology needs to witness to the experiences of the sufferer.

Pastorally attuned, the theology of trauma is wary of platitudes and how they may function in situations of trauma. Certain phrases capture whole theological systems: “It is God’s will.” “God is testing me.” “This is my cross to bear.” Theologians of trauma probe the theo-logic underlying these platitudes. If someone understands that God brings about their suffering in order to test their faith, what does this say about God? What if one fails the test? Theologians of trauma resist prescriptions about suffering because these prescriptions can diminish the reality of someone’s suffering, push it below the surface, or sacralize suffering as a good in itself. Theologians of trauma do not seek to judge these platitudes as good or bad but rather to interpret the impact they have on those who hold them.

After a friend lost her daughter in a tragic car accident, she told me that she does not think God willed her daughter to die. She is wrestling with the passage in Judges 11 about Jephthah, who offers his daughter as a sacrifice at God’s command. “I cannot make sense of a God who would ask a parent to do that,” she says. She rejects that notion of God. But then she told me that it does comfort her to think that it was her daughter’s “time.” This assertion assures her that life is not random or senseless.

Her process of coming to terms with her daughter’s death intersects with theological affirmations in her religious tradition, but it also departs from aspects of her tradition—a departure she is willing to defend on the basis of her experience. A theodicy-driven posture may insist on aligning her contradictory statements; a trauma-attuned posture allows for the contradictions.

What is clear is that this person is interpreting all Christian teachings through the lens of this life-shattering event and shifting her theology to account for the nuances of her life. She is acutely attuned to theological explanations and is asking hard questions. Preachers must be equally careful as they preach and teach about suffering. For those gathered at Good Friday services, there is not just one cross. The distinctive crosses that people bear are all brought into the sanctuary. Out of their experience, these parishioners are paying attention to what the preacher has to say.

In the aftermath of a traumatic event, Christians have often wanted to offer words not only of comfort but of spiritual overcoming. Traditional theology has focused on proclamation and the assertion of God’s victory over suffering. The message is “This event can be mastered.” There may be struggle, but the struggle will lead to something better. In clinical circles, the language of recovery is replaced by the language of resilience, to acknowledge the challenge of living with the effects of trauma rather than just moving beyond it. Many theologies, however, remain tied to the theme of recovery.

The experience of trauma dismantles notions of theology as a fixer, a provider of solutions. A move to “fix” things may interfere rather than assist in the process of healing. Theologians who have learned from trauma theory emphasize the importance of accompaniment, truth telling, and wound tending. Acts of witness and testimony acknowledge the reality of traumatic experiences that can never be fully brought to the surface of consciousness. This posture is not focused confidently on conveying theological or moral certainty. Instead, its confidence is in the healing power of giving a witness to suffering.

In response to trauma studies, theologians have turned to multiple resources throughout Christian history to provide alternative visions of suffering and healing. They turn, for example, to the Gospel narratives, emphasizing that each Gospel provides a unique account of how Jesus’ followers respond to the trauma of his crucifixion. The abrupt short ending of Mark’s Gospel is raw and attests to the shock of loss. It ends without offering any conclusion. The Gospel of John features multiple appearances of Jesus to the disciples following his death. Trauma readings pick up on the centrality of witness in John, which renders it more of a survivor narrative than a narrative of triumph. In Luke, the account of the disciples meeting the resurrected Jesus on the road to Emmaus underscores the problem of recognition that marks many experiences of trauma. Jesus appears as a stranger and makes himself visible to the disciples only indirectly, through the sharing of a meal. The resurrection appearances often begin with the disciples not knowing or not recognizing him. For readers attuned to trauma, the scenes of loss, mourning, confusion, and doubt in the Gospels are significant, not incidental. They provide models by which contemporary Christians can grapple with their own experiences.

Theologians have turned also to liturgical resources. Reviving traditions of lament in the Hebrew scriptures, they insist that communal practices of remembrance and lament are vital for the life of faith. Grief, loss, and pain can and should be held by communities who long for God’s transforming work. The Easter Vigil service features extensive readings of biblical passages in which God’s work of redemption is long and difficult to glimpse. The service begins on Holy Saturday in darkness and unknowing and gradually gives way to Easter dawn—emphasizing that life does not easily rise from experiences of death. The slow pace of the Vigil works against theologies that tend to jump quickly from Good Friday to Easter Sunday. Rethinking liturgical resources in this way, Christian communities can provide what theologian Serene Jones identifies as containers in which experiences of trauma can be held and transformed.

Theologians have also turned to ancient figures who wrestled with church teachings about suffering. For example, the 14th-century English theologian Julian of Norwich tries to reconcile what she knows about God with teachings that claim that God holds human beings blameworthy for their suffering. Julian insists, through careful development of an alternative vision of the Fall, that suffering does not come about through willful disobedience to God but is an inherent part of human existence. This vision of humanity draws on the teachings of Irenaeus in the second century: the real problem of our suffering is that in the midst of it we cannot see the loving gaze of God upon us. Julian’s vision challenges the sin/guilt paradigm that underlies the dominant theology of her day. She provides a wedge between sin and suffering that is very helpful for those who experience trauma. The question “What did I do to deserve this?” is morally freighted, often adding additional weight to someone who has experienced trauma. Julian helps lifts that weight.

These retrievals of tradition also acknowledge that for many people who experience trauma, Christianity has offered judgment, not good news. This judgment may live in our bodies, tied to deep experiences of shame and guilt. I hear repeatedly that churches are not sites of healing from violence but, instead, sites of the perpetration of violence. The sense that a person is at fault for what has happened to them is often threaded into Christian responses, sometimes unconsciously.

Many theologians writing in response to trauma work within existing theological traditions—liberation, feminist, womanist, disability, and queer theologies. These traditions focus on power dynamics and social determinants of trauma, considering the impact of trauma on whole communities. They highlight a move within trauma studies more generally to consider the social conditions that surround any event of trauma. Structural realities render some communities more vulnerable to harm because of the markers of race, gender, and sexual orientation. The term trauma provides a different way of voicing the impact of systemic and structural injustice. The labels or brands given to theology are less important than whether the theology meets people in the realities of their situations and prophetically addresses the powers and principalities that keep particular communities in positions of vulnerability. This effort requires weaving together pastoral, public, and prophetic commitments. Turning toward the realities of trauma rather than turning away from them requires spiritual muscles for long-term work

And yet the diagnostic framing of trauma theology is not without its limitations. It is easy for theology to become subsumed under a medical model of suffering. In a therapeutically driven culture, theological visions can help expose the assumptions of the medical model of suffering. For example, is the alleviation of suffering at all costs something to be theologically affirmed? Theologians working in this area are concerned about the commodification of care and the medicalization of societal problems. They call on the wisdom of religious traditions to question cultural views of health, wellness, and illness.

Knowing something about trauma should change the shape of Christian ministry. When we write sermons or offer pastoral care, we can keep in mind three lessons of trauma studies: The past is not in the past. The body remembers. The wounds do not simply go away.

The past is not in the past. In the timeline of traumatic experience, events are not over when they are over. Christian communities, through worship and ritual, can provide containers for practices of remembrance. We can incorporate into the calendar occasions for acknowledging what is known and not known about the past. We can emphasize the belief that God holds the memory of suffering, across time, in a suffering body. We can consider how the memories of past suffering might be reconciled in and through the work of Christ.

The body remembers. Many of our theologies are word-based and emphasize talk. As inheritors of Enlightenment thought, we often privilege the role of cognition—of knowing and believing—in the life of faith. This approach to faith targets our frontal lobe and often fails to address the role of the senses and of bodily knowing in faith. Christians need to pay attention to bodies and to how both mind and body may respond to certain words or stories. We can pay attention to breath, a primary metaphor for God’s Spirit. We can summon the breath, as God instructs Ezekiel, and witness to the hope that dry bones can come back to life.

Wounds remain. There is a lot we do not know and a lot we can never know about what wounds people carry and the variety of ways in which life marks them. We do know that wounds do not simply go away. How people narrate their wounds, through words, gestures, or even through inscriptions on skin (tattoos) is important. We should not try to sweep the wounds up into a tidy package. The focus for Christian leaders should be on our capacities to stay with these wounds rather than to look away.

The account of the resurrection in the Gospel of John offers an invitation to engage wounds not only as marks of death but as ways of marking life forward. The revealing of Jesus’ wounds after the resurrection is often interpreted as a sign that confirms his identity, points to the miracle of resurrection, and assures Christians that their faith is not in vain. These interpretations present the wounds as instruments to convince the disciples that Jesus is the Christ.

A reading informed by trauma turns us to the wounds of death that do not simply go away. They appear on the body of the resurrected Jesus to bring the past forward. This Gospel’s account presents the resurrected Jesus in ghostly form, as he moves through the walls of a locked room and stands in front of the disciples. But he is also very fleshy, as he invites Thomas to plunge his finger into his pleural cavity. The state of this body, as both ghostly and carnal, is figured in the resurrected Jesus.

Again, the challenges of witnessing directly to what is taking place are a mark of trauma readings of the Gospel. These accounts dismantle the primary senses and activate different body sensations, beyond seeing and hearing. Thomas is invited to touch. Bodily sensations are activated. Jesus breathes on the disciples—his gift to them is the power of breath, of God’s Spirit present with them, new air in the stale rooms that keep them locked down and afraid. Go, he tells them. Leave the room. The particularity of this body, identified by Christians as the Christ, is that in this body God holds those realities together, bringing what is unknown about the past forward but not allowing it to be pushed below the surface. The surfacing of wounds—to the disciples and to Thomas—is an insistence that wounds do not simply go away. There is work to do in coming to terms with past harms and in transfiguring wounds without erasing them.

These insights from trauma do not change the narrative. Instead, they give us a new angle of vision on the Christ who bears wounds, and a new starting point in caring for others.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Theology after trauma.”