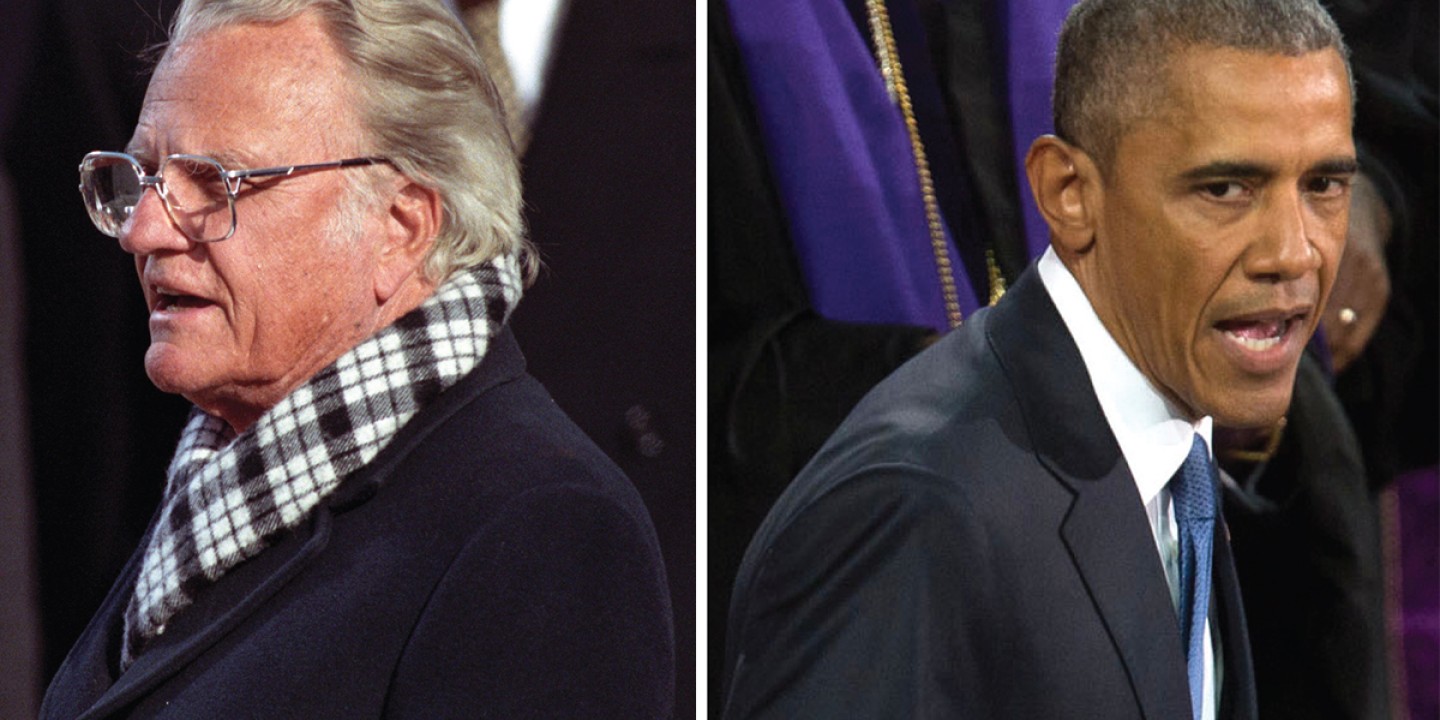

Billy Graham and Barack Obama each offered a pastoral voice in a time of tragedy

We need someone to speak to our moment, too.

Today’s pandemic scourge, coupled with a new awareness of centuries of racial injustice and economic disparities, has created pain of such magnitude that it seems unique to our time and place. It isn’t. Misery caused by the cruelties of nature, combined with the cruelties caused by humans, has afflicted people since time immemorial. Even so, this moment somehow feels unique because it is ours. Ours to suffer, ours to atone for, and ours to repair.

In times past, pastoral figures have periodically emerged to help guide the entire nation. Abraham Heschel, Theodore Hesburgh, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Martin Luther King Jr. spoke from the covers of national magazines. Dorothy Day and Fanny Lou Hamer spoke equally powerfully from more modest venues.

As we wait for a pastor to emerge in our current crisis, it’s worth returning to the words of two individuals who spoke in tragic settings in our nation’s recent history. In their mournful grandeur, both Billy Graham (who died in 2018 at age 99) and Barack Obama model how a pastoral benediction might help us find a way forward today.

The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, amplified by horrifying images on television, released emotional shock waves everywhere. A flood of patriotic grief followed. The components of the calamity were in one sense entirely different from today’s crises. Still, the result was in many ways the same: pain and grief surging like a tsunami across the entire landscape. And not just in the United States, but other parts of the globe too.

Three days after the attacks, President George W. Bush hosted a memorial service at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. The invited speakers reflected America’s religious pluralism. Besides the president, they included an Episcopal bishop, an imam, a rabbi, a cardinal, a mainline Protestant minister, and Graham, an evangelical, who offered the keynote address. The words of the other speakers, though important at the time, have largely faded. But not Graham’s.

Bush’s choice of Graham was not random. Among evangelicals, no other person came close in international recognition. Eighty-two years old and a celebrated preacher for more than a half century, he brought the respect earned by age and longevity in the public eye.

Graham’s talk followed a tragedy only deepened by the extraordinary heroism of first responders, many of whom sacrificed their own lives to save others. “This event reminds us of the brevity . . . and the uncertainty of life,” he said. “We never know when we too will be called into eternity.” Unlike self-appointed sages on both the right and the left, he did not offer a theological explanation for suffering. Rather, he said, the reason remains hidden in God’s mystery.

But he did assert that God understands the pain. After all, in the Christian reckoning, the torment of death on a cross, followed by a resurrection to new life, stands at the very center of history:

From the cross God declares, “I love you. I know the heartaches and the sorrows and the pain that you feel. But I love you.” The story does not end with the cross, for Easter points us beyond the tragedy of the cross to the empty tomb. It tells us that there is hope for eternal life, for Christ has conquered evil and death and hell. Yes, there is hope.

Graham then called his hearers to choose. Believe that life holds no larger purpose, or believe that God somehow holds history in his hands. Embracing the second option would not dull, let alone erase, the pain, but it would give grievers a wider context for framing their loss. Graham closed the sermon by reciting a stanza of the hymn “How Firm a Foundation.”

Graham was not a profound thinker or an eloquent preacher, but he dealt with serious things in serious ways. Newsweek religion editor Ken Woodward later said that Graham could make the simplest sentence sound like sacred scripture. By that point in his career, Graham seemed to stand above divisions, somehow transcending the welter of political and religious boundaries.

More than once during his presidency, Obama played a similar role. Most of his public words pertained to affairs of state or to the Democratic Party. But sometimes he, like President Lincoln, spoke as a pastor.

The challenge for Obama was extraordinary. For Graham, the pastoral role came naturally and the script was preset. Both were what the nation had come to expect. But Obama had to navigate the venerable distinction between church and state without violating the integrity of either one.

On June 17, 2015, pastor and South Carolina state senator Clementa Pinckney was one of nine people gunned down by a White supremacist during a Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston. Nine days later Obama delivered Pinckney’s eulogy to a capacity crowd at the College of Charleston TD Arena.

The audience had gathered, the president began, to honor a man who “embodied a politics that was neither mean nor small.” Pinckney had distinguished himself by how he conducted his life, “quietly, and kindly, and diligently.” Moreover, Pinckney had often marched as a prophet. “His calls for greater equity were too often unheeded, the votes he cast were sometimes lonely. But he never gave up.”

On that solemn occasion Obama’s words pivoted on a single theological point. “This whole week,” he mused, “I’ve been reflecting on this idea of grace.” Being the fine preacher that he is, Obama proceeded to define the concept. “Grace is not merited. It’s not something we deserve. Rather, grace is the free and benevolent favor of God as manifested in the salvation of sinners and the bestowal of blessings.” With an unerring sense of timing, the president paused, then repeated the momentous word for emphasis: “Grace.”

The nation has not earned grace, continued Obama, given the perpetuation of its original sin, its moral blindness, its complacency. But God has bestowed it regardless. “It is up to us now to make the most of it, to receive it with gratitude, and to prove ourselves worthy of this gift.”

Implementing grace in our personal and national lives is no solitary endeavor, Obama went on. Only in our “recognizing our common humanity by treating every child as important, regardless of the color of their skin or the station into which they were born,” can grace take root and become real.

A great-souled man, Obama did not suggest that grace is the peculiar possession of any one person or group. “People of goodwill will continue to debate the merits of various policies . . . and there are good people on both sides of these debates.” The challenge requires deep empathy, the kind that grows from “recognition of ourselves in each other.” It is more than just working together, trying to see eye to eye.

Though the president did not use the term social gospel, he articulated its message with brilliant succinctness:

Our Christian faith demands deeds and not just words; that the “sweet hour of prayer” actually lasts the whole week long . . . to feed the hungry and clothe the naked and house the homeless is not just a call for isolated charity but the imperative of a just society.

At the end of the eulogy, in what is perhaps the most remembered part, Obama took courage in hand and proceeded to sing—not recite but sing—the first lines of what may be the best-loved hymn of all time: “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound / That saved a wretch like me. / I once was lost, but now I’m found; / Was blind, but now I see.”

At different periods, Americans have heard stirring words rolling from various tongues: in Thomas Jefferson’s “all men are created equal”; in Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a woman?”; in Julia Ward Howe’s “Mine eyes have seen the glory”; in Abraham Lincoln’s “mystic chords of memory”; in Emma Lazarus’s “huddled masses yearning to breathe free”; in John Gillespie Magee Jr.'s “slipped the surly bonds of earth” to “touch the face of God,” quoted by Ronald Reagan; and, of course, in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream.”

Does the nation need or even want a single authoritative pastoral voice? It’s a fair question, even during times of national trouble. Graham previewed that inquiry when reporters asked him, as they often did, who would succeed him. Often he quipped, “No one,” since “you have already seen too much of me.” But turning serious, he said he trusted that his message of God’s love and forgiveness would be carried by thousands of unheralded evangelists who had never heard his name.

Obama may never have addressed such a question directly, but he certainly did indirectly—and perhaps equally powerfully—through his example. His deeds suggest that we’re all called to be pastors to one another. Those gifted with a public voice may use it as a platform for addressing the common good. At the same time, ordinary folk in their own small but important ways may use social media to worship faithfully and address the common good even through the challenges of COVID-19.

Many voices with a global resonance speak in their own tones, from their own traditions. The best of these, like Graham and Obama, try to detoxify the poisonous streams running deep in our environment, society, and economy. They speak beyond their tribal self-interest and seek to sow seeds that will come to fruition after they are gone.

The stage is set. As the death toll mounts, we wait for research scientists, medical professionals, and political leaders to do their work. We also wait for a pastor—or better yet, uncountable pastors—to speak not just to some but to everyone. A nation can survive without remembering eternal things. But the need for humility, repentance, forgiveness, and faith in the future is always a word in season.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Billy and Barack.” This online version was edited on December 21, 2020, to clarify that the quote from Ronald Reagan is itself a quote from John Gillespie Magee Jr.