Americans have never agreed on what religious freedom means

Peyote use has been defended with religious liberty arguments. So has Bible reading in public schools.

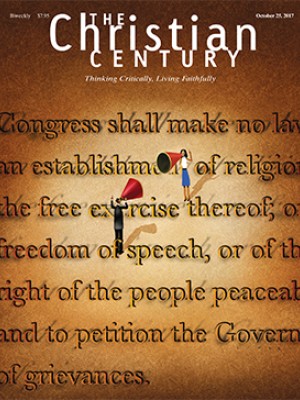

The American ideal of religious freedom has rarely seemed more controversial than it does today. While some continue to see it as the “first freedom” that grounds American democracy, others contend that it unfairly privileges those who claim the mantle of religion. Public commentary on all sides of this debate pits religious freedom against progressive values such as reproductive rights for women and equality for LGBTQ people—and even more broadly against the ideals of diversity and inclusion for all.

Such analysis flourished after Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014), when the Supreme Court ruled that privately held corporations whose owners claimed religious objections could not be required, under the Affordable Care Act, to include coverage for contraception in the insurance they provided for employees. The affected employees could still access such coverage, the court noted, through a process that the Obama administration had already crafted to accommodate religious nonprofits with the same objection. But this compromise did not resolve the dispute. Over a hundred nonprofits protested that simply filling out a form to facilitate contraceptive coverage made them complicit in something that violated their religion. While the legal issues here have not yet been resolved, the court ruled in a more recent case (Zubik v. Burwell, 2016) that while the government was free to provide such coverage, objecting institutions could not be penalized for their failure to cooperate.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Similar questions remain unresolved regarding same-sex marriage and transgender rights. Should private businesses (or individual government employees) be required to serve same-sex couples, whose marriages are now protected by law, even if they believe homosexuality to be against the will of God? The Supreme Court will address that question this term in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission.

Given the stakes of these debates, some on the left end of the current political spectrum have come to see the freedom of religion as a smokescreen for bigotry, perhaps even harmful to a flourishing and free society. In September 2016 Martin R. Castro, then chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, wrote: “The phrases ‘religious liberty’ and ‘religious freedom’ will stand for nothing except hypocrisy so long as they remain code words for discrimination, intolerance, racism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, Christian supremacy, or any form of intolerance.” Castro’s statement accompanied a commission recommendation that civil rights protections be prioritized over religious exemptions, which, it advised, should be “weighed carefully and defined narrowly on a fact-specific basis.”

When that commission report came out, a diverse set of American religious leaders—including evangelical, Pentecostal, Catholic, Mormon, Jewish, Muslim, and Hindu representatives—immediately sent a letter of protest to President Obama and to congressional leaders. The commission had stigmatized “tens of millions of religious Americans,” they claimed, and its recommendations threatened the “first freedom” of a nation founded “in substantial part due to the religious ideas of the founding generation.” These letter writers saw the civil rights commission as agents of a state secularism that would banish anyone with strong religious views from political life.

Many religious conservatives—and some who may not identify as conservatives in other ways—see religious freedom not merely as an essential protection for their own rights but as the very heart of American democracy, an essential defense against forces that they fear will destroy it. These fears fostered many people’s convictions about the importance of the appointment to replace Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court and played a part in the election of Donald Trump.

Historically speaking, Americans have never agreed on what religious freedom means or how it should be applied. Religious groups of all kinds—whether the bulk of their adherents were recent immigrants, racial minorities, Native Americans, or the descendants of colonial white settlers—have invoked this freedom in many different ways to advance a multitude of goals. At times it has been a valuable tool for persecuted groups, providing a means of self-defense in the courts of law and in the courts of public opinion. But all too often the ideal of religious freedom has worked in favor of the majority white Christian population. Cultural assumptions about what counts as religion were set by that majority in the first place, making it far more difficult for traditions that do not fit Christian norms to gain public sympathy or legal traction for their claims. Religious traditions that are primarily associated with racial minorities have faced the added challenges of racial discrimination.

The loudest demands for religious freedom have generally privileged the majority. Campaigns for Bible reading in the public schools or for blue laws that enforce a day of rest on Sundays, for example, were successfully advanced by some (as well as opposed by others) in the name of religious freedom. In the 19th century, pro-slavery voices invoked religious freedom to defend the “peculiar institution,” attacking abolitionism as a threat to the moral foundations and the religious convictions of the (white) South. Up until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, white southerners and their northern allies defended the legal regimes of segregation in much the same way.

The winds of religious freedom began to shift in the decades after World War II, when the civil rights and civil liberties movements gave new traction to minority voices of all kinds. Religious minorities advanced newly ambitious First Amendment claims starting in the 1940s and 1950s, when a series of prominent cases expanded the range of the free exercise clause, first making it applicable to the states, rather than just the federal government, and then recognizing new protections for individuals and minorities over and against communal and majority norms. (Note the contrast with the current debate, where religious freedom appears to protect the rights of a Christian majority and to work against civil rights for individuals and minorities.)

This trend arguably peaked with Sherbert v. Verner (1963) and Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), cases involving the Seventh-day Adventists and the Amish, respectively: two predominantly white sectarian Protestant groups with generally picturesque public images. Ruling in their favor, the Supreme Court created a new standard requiring that religious practices be accommodated as much as possible even when that meant granting exceptions to otherwise applicable laws.

In this period, movements for civil rights and minority empowerment made appeals to religious liberty. Prisoners from a variety of racial minority and immigrant religious traditions—including Muslims, Native Americans, and Sikhs—argued successfully for the right to their own distinctive dietary, dress, and devotional practices in prison. The feminist movement of the 1970s and 1980s also employed religious freedom as a pro-choice slogan. Each woman had the right to decide the morality of contraception and abortion according to her own conscience, they argued, and any legal restrictions on this freedom represented an unconstitutional establishment of religion.

Because antiabortion politics had long been associated with Catholicism, this approach relied in part on Protestant and liberal fears of Catholic power. And in fact the court’s decision in Roe v. Wade hinged more on the right to privacy than on free exercise as such. (Both arguments rested on the priority that prevailing legal philosophies granted to the rights of the individual.) Nevertheless, the fact that religious freedom was once associated with the pro-choice movement reveals just how dramatically cultural politics have changed in the intervening decades.

During this same time, conservatives in the emerging culture wars were developing their own claims to religious freedom. The new religious right took shape as part of a wider backlash against the civil rights, civil liberties, and feminist movements, all of which conservative Christians viewed as aspects of an unacceptable secularization of public life. Many of them were appalled when the Supreme Court ruled in the name of religious freedom against any teacher-initiated and state-authorized prayers in the public schools. (Others, including many Christians, alongside Jews and other religious minorities, saw these rulings as a triumph for religious freedom because they barred the open endorsement of a majority religious practice.)

The new religious right really gained momentum and became an institutional force specifically in protest against the decision by the Internal Revenue Service to strip Bob Jones University of tax-exempt status because of its practices of racial segregation on campus. More generally, the new movement wanted to defend the private Christian schools that had mushroomed in the 1970s as white Christians sought to escape from the newly integrated public schools.

Religious freedom provided a conveniently high-minded rationale for segregated schools, and soon conservatives were protesting all manner of fair labor and civil rights regulations in its name.

“Church schools and many preachers are being harassed by the liberal forces, and their religious liberties are being tampered with,” warned Jerry Falwell in 1983. “When decent citizens and religious leaders can be threatened and thrown into jail just for sending their children to a church school or preaching the Word of God, something is drastically wrong!” For Falwell’s Moral Majority and many likeminded evangelicals, religious freedom was a rallying cry for the right to practice and proclaim Christianity in the public sphere, for the defense of a traditional moral establishment with its social and racial hierarchies intact, and ultimately for a resurgent view of the United States as a “Christian nation.”

The heyday of minorities making legal claims on the basis of religious freedom came to a crashing halt in a case involving Native Americans, whose traditions have more often been persecuted than protected under U.S. law. In Employment Division v. Smith (1990), the Supreme Court allowed the state of Oregon to deny unemployment benefits to Alfred Smith and Galen Black, two Native American Church members who had been fired for violating a state prohibition on the use of peyote. Their free exercise claim was denied on the grounds that the state had no constitutional obligation to provide an exemption to the law even without demonstrating a “compelling interest” for that refusal.

The Native American Church had over the course of its long history gained very tentative and partial success in its claims for the use of peyote as a religious practice, often comparing it to the sacramental use of wine in Christianity. But at the height of the nation’s War on Drugs, that comparison apparently held little weight. In dismissing Smith and Black’s claims for this Native American practice, the court effectively overturned its own standard of accommodating religion.

Churches, religious groups, and civil liberties organizations across religious and political lines were uniformly appalled at this decision and joined together in a powerful—though ultimately temporary—alliance against it. At their urging Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993, a law designed to restore the right to religious exemptions that the Smith case had shattered. According to the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs, which had long supported the separation of church and state as a prerequisite for religious freedom, RFRA was “the most significant piece of civil rights legislation dealing with our religious liberty in a generation.”

In light of the current scene, it’s surprising to recall that it was not pro-choice groups but abortion opponents, especially the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, who initially hesitated to support RFRA. As the Christian Century reported, the bishops worried that “its language could be used to overturn state restrictions on abortion and to challenge tax exemptions now enjoyed by religious groups.” In other words, like the pro-choice feminists, they assumed that religious freedom—and government accommodations for religious practice—would generally work against the pro-life cause.

Meanwhile, other Christian conservatives saw an opportunity to reframe the national conversation. Less than a year after RFRA became law, born-again evangelical icon Chuck Colson and neoconservative Catholic intellectual Richard John Neuhaus began to think through these implications in their co-authored “Evangelicals and Catholics Together,” a statement that the leading lights of both groups would sign. Most Protestants up to the mid-20th century had seen Catholicism as the single largest threat to religious freedom, so the evangelical-Catholic alliance was significant. Colson and Neuhaus acknowledged the profound theological differences that divided them but went on to define a set of core convictions around which they and their coreligionists could unite.

They argued that religion had in recent years been made “marginal” and that it should now be restored to its proper place at the heart of “the American experiment.” Although they expressed concern for all religion—a nod to the cultural value of religious pluralism and to the ideal of religious freedom for all—their real interest was in Christianity. They invoked the language of religious freedom exclusively in reference to conservative positions in the culture war debates over abortion, pornography, and—in continuity with the racial politics of earlier decades—parental choice in education. “Evangelicals and Catholics Together” made no reference to those Americans who claimed no religious affiliation or to the issues that concerned racial-religious minorities, such as the government’s surveillance and harassment of black Muslims or the destruction of Native American sacred lands.

All this history helps make sense of the politics of religious freedom that we witness today. Christian conservatives were increasingly able to monopolize the public discourse on religious freedom—and indeed have become the assumed referent for virtually all references to religion in American public life. Even as the courts affirmed cultural shifts in favor of same-sex marriage and other LGBT rights, conservatives have won a series of legal battles in the name of religious freedom and have high hopes for more. Religious freedom has thus come to be associated almost entirely with conservative Christian priorities and concerns.

The partiality of this model is visible in the space between President Trump’s controversial executive order on immigration, otherwise known as the “Muslim ban,” and his executive order on religious liberty. Like “Evangelicals and Catholics Together,” both orders claimed to protect religion or religious minorities but in reality only advanced the goals and interests of socially conservative Christians.

The immigration order, even in its first version, made no mention of Islam but instead spoke in coded terms about the danger from “foreign born individuals” who “harbor hostile attitudes” toward the United States and its “founding principles.” The initial order suspended the admission of refugees except in cases of “religious-based persecution” where the refugee belonged to a “minority religion in the individual’s country of nationality.” Couched in the language of religious freedom, this policy was quite obviously intended to allow Christians, not Muslims, into the United States.

When federal courts ruled this order unconstitutional, the administration released a second version that began by insisting that nothing in the first order had been “motivated by animus toward any religion.” In hopes of toeing the constitutional line, the new order did not specify religion as the basis for any exceptions to the suspended refugee program. Instead it allowed administration officials “to admit individuals to the United States as refugees on a case-by-case basis, in their discretion,” if they determined that these individuals posed no security threat and where “the denial of entry would cause undue hardship.” All of this further abstracted the issue. Exceptions were to be granted by discretion, a policy that would allow officials to tacitly privilege Christians without mentioning Islam, Christianity, or even the category of religion at all. At the same time, as in the first version, the new order used a list of predominantly Muslim countries and the coded language of “aliens” and “terrorism” to invoke the racialized fears of Islam that Trump’s campaign had helped to build.

Trump’s religious liberty order, released several months later, used the generic terms religion and religious freedom to support a set of issues that have in fact been pushed by a socially conservative and mostly white Christian constituency. A draft version, leaked and published by the Nation in February 2017, promised sweeping religious liberty protections for both “persons and organizations” when “earning a living, seeking a job, or employing others; receiving government grants or contracts; or otherwise participating in the marketplace, the public square, or interfacing with Federal, State, or local governments.” It went on to specify that employers could refuse health insurance coverage for abortion and contraception, that agencies offering “child-welfare services” such as adoption could operate entirely according to their religious convictions, and that those who believed that marriage “should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman” could not be penalized for acting on that belief.

The final version of the order released in April was shorter and less specific, and was apparently drafted by someone versed in constitutional law. But the specifics it did include—promises that “political speech” would not result in religious organizations losing their tax-exempt status and that “conscience-based objections to the preventive-care mandate” would be permitted—were equally tailor-made for a conservative Christian constituency. The final order did not substantively change federal policy on religious freedom, but it was a significant gesture on behalf of the Christian right. It was a clear repudiation of the civil rights commission and a symbolic if not particularly substantive reward for white evangelical and Catholic support in the 2016 election. It was not an endorsement of religious freedom framed with Muslims, Native Americans, African Americans, or any other racial-religious minority in mind.

The current cultural associations between religious freedom and conservative Christianity are powerful but not inevitable. Political tides can change, and even the most hegemonic discourses can be transformed to move toward more just and inclusive ends. For example, American Muslims and their allies have also invoked the ideal of religious freedom to resist Trump’s immigration order and to defend the construction of new Islamic centers when local governments have tried to halt them. And despite the current climate of fear and hostility against Islam, these claims have mostly succeeded. So while many progressives might despair at the current politics of religious freedom, and some scholars argue that as a legal principle it does more harm than good, the lesson I draw from this history is that religious freedom (like any culturally powerful ideal) can be invoked and redefined by all sorts of people toward all sorts of ends.

In my view, religious freedom should not be given higher priority than any other liberty and certainly should not trump the principle of equal protection for individuals and minorities under U.S. law. But this negative framework need not limit our vision. The history of religious freedom is far from over. Liberals and progressives—whether or not they claim a religious commitment themselves—should embrace rather than reject the ideal of religious freedom and put the ideal to work alongside other civil rights guarantees on behalf of those who need it most.

A version of this article appears in the October 25 print edition under the title “Whose religious freedom?”