Virginia Mollenkott’s Women, Men, and the Bible shaped my life

The lesbian evangelical scholar bravely shared her view of God—in love.

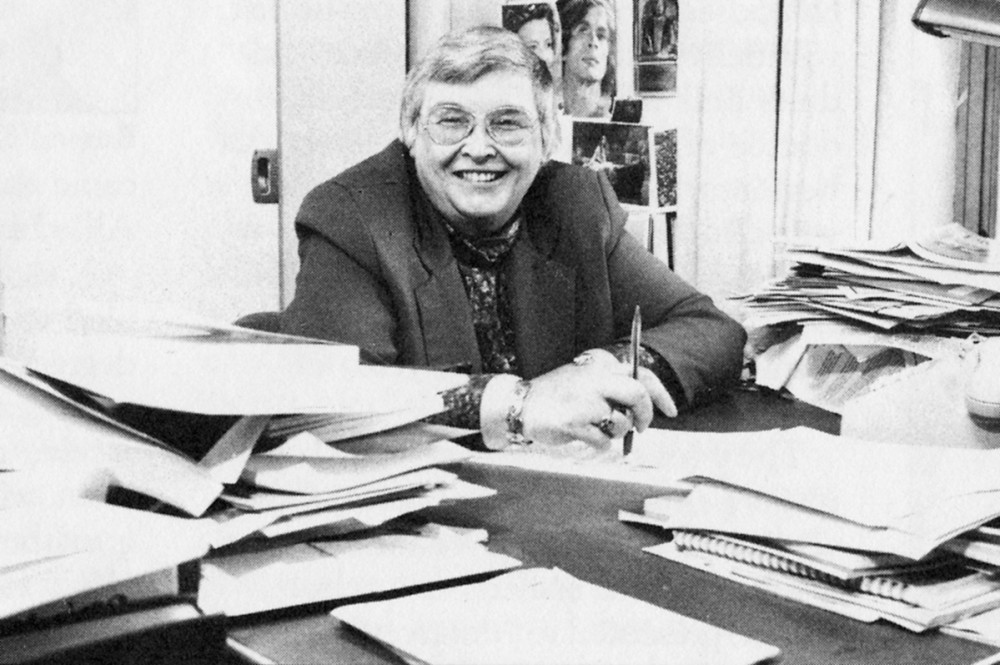

When biblical scholar, feminist, and lesbian evangelical Virginia Ramey Mollenkott died last fall, my father forwarded me her New York Times obituary and reminded me that she’d had a profound effect on his life. I didn’t need reminding.

In the spring of 1988, the summer before my junior year in high school, he handed me a copy of Mollenkott’s book Women, Men, and the Bible. If I remember correctly, he said something like, “Don’t let anyone else tell you what is in here. Read it for yourself.” I had the sense of being handed something important but also secret, maybe even potentially dangerous—the feeling of being invited into a society. My adolescent mind instantly divided the world into “people who read Virginia Mollenkott” and “people who tell you not to.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I read it voraciously, passionately. I all but memorized it. To this day, I can recite key arguments that leapt off the page and into my adolescent life. “Jesus boldly pictured God as a woman.” Genesis 1 is not a prescription for female and male identity; it is a description of the world men and women inhabited.

Mollenkott was an evangelical, and so was I. This label allowed her into my life. In a world that divided people into safe and unsafe, us and them, she was one of us. But in truth, there was nothing safe about Virginia Mollenkott.

She was born into a Plymouth Brethren family, and when she fell in love with an older woman, her mother sent her to a Christian boarding school to end the relationship. Later, at Bob Jones University, she continued to struggle with her sexual identity and self-understanding. She confessed to a professor that she loved women; the professor urged her to get married right away. She obeyed. The marriage did not last, and during the 1970s, now Dr. Mollenkott, she began to write about Christianity, gender, and sexuality in ways that would profoundly impact my life.

Women, Men, and the Bible, which sits on my shelf with its light-blue cover and its male and female symbols, has survived many book purges. I keep it because it represents a liberating moment in my development. It reminds me of the way a book can walk into your life and set you free.

When I look at this book now and see my adolescent handwriting in its margins, I realize there is nothing particularly radical about it. It argues, for example, that Christian women ought not to be excluded by referring to Christians as sons or brothers. It argues that God ought not to be thought of as male or female.

The power of the book for me, perhaps, was less about how it shaped my mind and more about how it shaped my life. I read it deeply and completely. I poured it into my veins. It became a part of me the way that few books ever have.

When I left for my Christian camp that summer, Virginia Mollenkott went with me. I didn’t carry the book with me, but by then I didn’t need a physical copy.

The camp was a windy, weedy place on the edge of a lake in North Dakota. I had gone there every summer of my adolescence. I didn’t question any of the rituals surrounding this event. I brought my bags to the church early on a summer morning, piled into the soon to be miserably hot van with my closest friends, and drove the five hours north on I-29 to arrive at the barren shores of the small lake.

This particular year a special guest was spending the week with us. He gave presentations in the morning to the whole camp and then did special sessions in the afternoon on narrower topics. I won’t say his name. There is no reason for it. Suffice it to say that he was a representative of the broader church organization of which this camp was a part. He was a person of authority. I imagine, from what I know now, that some of the camp’s organizers thought it was an honor that he came to us and others thought it was a hindrance, and everyone gave him all the space he wanted to do and say whatever he wanted.

What he wanted to say was as anti–Virginia Mollenkott as it could possibly have been. He drew a ladder on a flip chart stationed on an easel at the front of the slightly moldy-smelling room, showing us God’s natural hierarchy. There were animals at the bottom of this hierarchy, then women, then men—who were by nature closer to God and thus were to be obeyed by women in all things.

I felt a strange heat on the back of my neck, a nausea in my belly. I did not know whether to stand up quietly and walk out of the room or to sit quietly in the agony. All the while, Virginia whispered in my ear. “By Jesus’ definition . . . biology is not destiny. . . . Spiritual commitment is destiny.” “The Christian way of relating is . . . mutual submission and mutual service.”

I don’t remember whether I stood up, but I did make my agony known. I didn’t shout or storm out. I didn’t keen or wail—although in some ways I wish I would have. It would have been an act of mourning for every woman who had sat in that place, whose basic humanity and dignity had been questioned in the name of religion, who had sat patiently while she was told who she was and who she wasn’t.

I started whispering my pain—first to my friends, who looked at me puzzled. Was I not accustomed to old men telling us how things are and us nodding along, ignoring them politely while we passed notes and created our own reality? Isn’t that what we had always done? How was this different? Then to camp counselors, who gave me looks I couldn’t read or understand but whose gestures left me feeling empty-handed. I saw that I was alone.

Eventually, I decided I would speak to the man himself. I would tell him of the pain I was in; I would quote Virginia Mollenkott to him and see if he would respond. No one intervened. No one told me that it was a bad idea to try to move from book to world with such a gesture as I had in mind.

I found him at breakfast, sitting alone with his pancakes. I took a deep breath, triple-dog dared myself, and walked over to his table. Here’s what I remember: he didn’t once look at me. Not once. I don’t remember if he argued with me or simply ignored me. It could have been either one. But not once did his eyes meet my eyes. He looked away. He looked down. And I felt shame. As I was doing the bravest thing I had ever done, I felt shame.

I walked away. This would be a really dramatic story if I had just kept walking, down the dirt road that led out of the camp, to the highway, and then all the way home. If I had done that, it likely would not have taken me quite as long to walk away from that form of religion. Instead it took time and more encounters and more books and more years.

I don’t believe that it was Mollenkott’s arguments, at the end of the day, that made a difference in my life. It was her compassion. Mollenkott’s work contains great compassion for girls like me. It was her compassion that gave me the courage to speak to that man that day and allowed me to stay in conversation with the Bible and with the Christian tradition. It surprises me to this day.

I know many people who have turned away from the religion of their upbringing, and for good reasons. I do not judge that choice. But as Howard Thurman says, “Love loves; this is its nature.” My own intellectual and personal journey began that day in North Dakota, emboldened by a braver woman who looked plainly and clearly at her own life and chose to tell the truth about it in love with love.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A book’s compassion.”