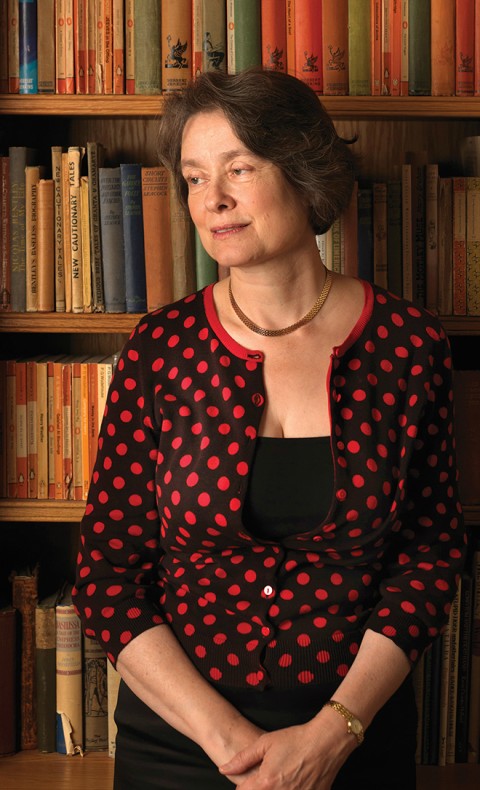

Why the world needs Sarah Coakley

Coakley's kind of theology requires more than claims. It needs prayer.

Let us imagine a truly dreadful possibility. What if there had been no Sarah Coakley, theologian? (I should stipulate that in this alternate history Sarah Coakley is not written out of existence but merely finds some other fulfilling form of labor.) To be sure, this seems unlikely. According to interviews, Coakley knew she wanted to be a theologian by age 12. But let us imagine that through some catastrophic mishap Coakley’s prodigious theological talents had been effectively squashed early on.

In this dire reality, there would have been no Powers and Submissions, no The New Asceticism: Sexuality, Gender and the Quest for God; no God, Sexuality, and the Self. We would have none of the edited volumes that Coakley has shaped, nor the graduate students whose work she has helped to guide. The 2012 Gifford Lectures would have been given by somebody else. How might theology be different?

Academic theology might well have produced someone formally similar to Coakley, but I dare say that person would be less interesting. To be sure, Coakley’s work stands at such appealing intersections that its appeal can tend to seem inevitable. Of course the spiritual senses can provide a way out of contemporary theological cul-de-sacs. Of course it is worthwhile for theologians to consider transformative desire, particularly if we want to say something thoughtful about bodies instead of scolding or ignoring them. Of course theology will need to avail itself of the best of other disciplines and should result in a vision for life rather than just a set of claims. Judging from the regard in which Coakley’s work is held, these are the kinds of moves that many people want contemporary theology to make. They are certainly more invigorating than either cranky nostalgia or fatuous individualism, to mention two of the more shopworn theological options.