Saints and doubters

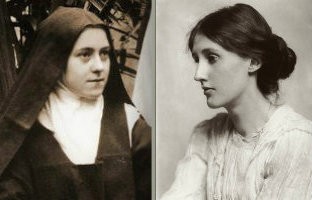

Are faith and doubt opposites? Thérèse of Lisieux and Virginia Woolf are part of the same history.

Leslie Stephen famously gave up his priestly orders—and with them, his academic appointment at the University of Cambridge—when he realized that he could no longer accept the story of Noah as sacred truth. His essays on agnosticism drew his future wife, Julia, to him. She had lost her beloved first husband to an early death, and her Christian faith along with him. Stephen’s essays were a balm to her, an assurance that morality did not depend upon religious belief.

Their daughter, Virginia Woolf, raised without a faith to lose, sought new forms of the sacred in her writing, new expressions of religious experience focused around what she called “moments of being”—moments when the pattern through which we are all connected is briefly illuminated.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Thérèse of Lisieux was born eight years after Leslie Stephen resigned his post and nine years before Virginia was born. At first glance, Thérèse’s life was completely different from theirs. The Stephen family descended from evangelical Protestants; Thérèse’s family, from pious Roman Catholics. At the age of 15, Thérèse entered a Carmelite monastery. Nine years later she died of tuberculosis. She became famous through her autobiography and her letters for her “little way” to God.

Thérèse’s “little way” was a modest approach to the great task of cultivating holiness. In her ordinary interactions with family and community, she tried to find opportunities to cultivate love. When her tired and cranky father scolded her on Christmas Eve, she resisted the impulse to cry and felt charity enter her soul. When she heard that a criminal was to be executed, she devoted herself to praying that he would turn to God in the end. When she was bent over the laundry trough in the convent and the nun next to her kept splashing her with dirty water, she offered up her aggravation in love to Jesus. “My dear Mother,” she wrote to her prioress about this episode, “you can see that I am a very little soul and that I can offer God only very little things.”

Was Thérèse’s way too little? Some have thought so. She has been described as sentimental, mawkish and even saccharine. With all that is going on in this suffering world, did she really think God would notice how she responded to being splashed in the laundry room?

But Thérèse’s small attempts to live a vocation of love in ordinary exchanges with others prepared her to love in the most difficult of circumstances. On the night before Good Friday in 1896, Thérèse had a coughing fit. When she awoke the next morning, she was covered in blood and knew that she had begun to die. At first she was filled with joy at the thought of joining Jesus in heaven. But by Easter Sunday that joy was gone, and it never came back. She said it was like living in a country upon which an impenetrable fog had settled. Try as she might she could not recover the joyful confidence she had had in God’s love and care and promises.

But even with her vision of God’s love obscured, she kept on following her little way. “While I do not have the joy of faith,” she wrote, “I am trying to carry out its works.” Thérèse was only 24. She had hoped to move to the Carmelite house in Hanoi; she had hoped to be a missionary; she would have liked to have been a priest. She struggled to keep her face turned toward the direction where she thought God was hidden; until the end she kept praying for others, kept trying to make her life an act of love.

People around the world cherish St. Thérèse’s little way because she shares the experiences of which all our lives are made and makes choices available to us all: to listen closely to another rather than remaining distracted; to respond to another with generosity rather than impatience; to resist meeting anger with anger. She taught herself how to keep loving even as she suffered and doubted. A photographic exhibit of her life, prepared by the Friends of Thérèse and of the Carmel of Lisieux, is currently traveling through prisons and hospitals, shelters and orphanages, bringing Thérèse out of the haze of sweetness that so often obscures her and into the realm of human struggle where she most clearly speaks.

Faith and doubt, like religion and science, are often posed as opposites. But Leslie and Julia Stephen, Virginia Woolf and Thérèse of Lisieux, whose lives overlapped, are part of the same history: they are human beings seeking new ways to live as the faith of earlier generations proves hard to hold onto. It is interesting that both Virginia Woolf and the child-saint of Lisieux found glimpses of the really real in ordinary, fleeting, “little” moments that lit up, with the force of revelation, a larger vision. They challenge us to seek such a vision in our own experience of the world, among our own doubts and hopes. On All Saint’s Day I’ll remember them all, saints together, under one wide sky.