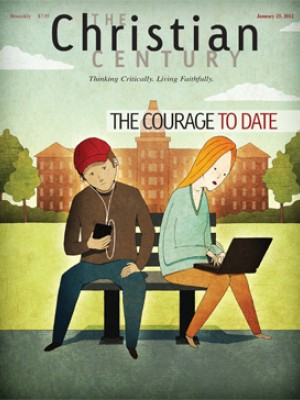

Mating games: Changing rules for sex and marriage

Read Amy Frykholm's interview with Kerry Cronin, Boston College's "dating doctor"

Read reports from college chaplains on campus sexual culture

Equal marriage is a social experiment of yet unknown proportions. No wonder we are confused. Most of our social scripts—from romance novels, fairy tales, movies, the advice that we gleaned from our parents and grandparents—are based on older forms of marriage that placed little value on emotional intimacy, sexual compatibility, shared (as opposed to specialized) skills and interests, or equal decision making.

Consider that it was only in the late 18th century that society began to approve of love as a primary consideration in the choice of a spouse. Only in the early 20th century did mutual sexual satisfaction become an accepted goal of marriage. Not until the 1920s did women even have the right to vote. Well into the 1960s it was legal to set lower wage rates for female employees, to exclude women from many occupations and to fire them if they got married or decided to have a child. And as late as the 1970s, most state legal codes defined the husband as head of the household, giving him final say over many family decisions, and refused to recognize the possibility of marital rape, because, the courts held, a woman's wedding vows implied a permanent consent to intercourse.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Even as wives won more legal rights during the 1950s and 1960s, they faced an army of psychiatrists, sociologists and marriage counselors telling them that only a "deviant" or "neurotic" woman would wish to use those rights. The "normal" woman, as psychiatrist Helene Deutsch put it, renounced all personal aspirations—not out of coercion, as in the bad old days, but because she realized that her greatest fulfillment would lie in celebrating the achievements of her husband. It was abnormal and unfeminine, women were told, to have any interests and desires beyond the kitchen, the bedroom and the nursery. And in the bedroom, although the "truly feminine" wife was always sexually available to her husband, she was also passive, never threatening his masculinity by asserting her own sexual needs.

We have come a long way from the 1960s. Young women have rejected the old feminine mystique almost in toto. Few women today feel they have to "play dumb" to attract a man, as 40 percent of college women said they regularly did back in the 1950s. They feel perfectly comfortable excelling at sports and aspiring to occupations that would have once been unthinkable for women. They have also made a serious dent in the rigid sexual double standard of yesteryear, asserting their right to sexual agency.

But gender inequities persist. Although education now outweighs gender in determining pay rates, women are still seen as the default parent, expected by their husbands and society at large to make most of the work adjustments needed after the birth of a child. And as in earlier eras, the mass media attempt to channel women's demands and desires into arenas that can be packaged and sold, whether as products for female consumers or as entertainment for others. In the 1970s, advertisers tried to use women's rebelliousness as a way to sell cigarettes, as in the famous ads featuring a sassy woman smoking a Virginia Slims cigarette under the slogan, "You've come a long way, baby." Today the mass media assure women that yes, indeed, they can be anything, but they need to dress and act in ways that advertise their sexual availability—what I call the "hottie mystique."

The equation of liberation with hypersexuality is very problematic, and I fully sympathize with observers who are appalled when they see shows like Girls Gone Wild, listen to the lyrics of much modern music, or just observe what mainstream department stores think are appropriate clothes for preteens. But it is important not to get hysterical about this development. Clearly, some young women do feel pressured to consent to sexual behaviors that have little to do with their own sexual pleasure or empowerment. But women also feel more free to say no to unwanted sex. And young men, on the whole, seem to respect that. Several victimization rates have fallen dramatically over the past 20 years.

The hookup scene or "friends with benefits" culture may be shocking to many. But we should not be nostalgic for an era when women could not admit to their sexual needs and were labeled sluts when they did engage in sex. I interviewed one woman, married with three children in the 1960s, who told me that she had lost her virginity with her husband before marriage. Thirteen years later, he would still throw it up to her during an argument: "If you gave in to me, how do I know you weren't doing it with other men?"

The practice of hooking up has disadvantages for women, but so did the old practice of dating, when women were allowed no initiative in starting a relationship and were often manipulated into having sex by an elaborate courting ritual that was abruptly terminated when the man "got his way." At least in a hookup, where the "no strings attached" rule is explicit, the guy doesn't pretend to be interested in a relationship in order to get the sex he really wants.

Hooking up is an emerging institution that is responding to a real challenge facing college students: how do you meet your sexual needs when you don't necessarily want to be involved in a relationship that leads to marriage and you don't want to take the risk of seeking out total strangers in unsafe places for what previous generations called the one-night stand?

For all the hysteria that surrounds the practice of hooking up, it's worth remembering that hookups are most likely to occur among the sector of the population that has the best shot at eventually establishing a lasting marriage—college-educated youths who postpone marriage until they have completed their education and established a certain degree of financial security.

This paradox is only one of many associated with the transformation of the old rules of sexual behavior, courtship and marriage. In 1960, half of all women married before they left their teens. The average length of courtship for marriages formed in the 1950s was only three months. This arrangement produced relatively stable marriages, in part because gender stereotypes were so extreme and in part because men and women had so few other options for organizing their lives. In the absence of antidiscrimination laws, women depended on men for financial support; in the absence of permanent press shirts and easy take-out food, men depended on women for meals and housekeeping. Sometimes friendships developed on top of marriage, but you could construct a lasting marriage pretty much on the basis of adhering to gender stereotypes alone. No longer is that true. Deep mutual understanding between partners and good negotiating skills are much more necessary than they used to be. In a successful marriage, education and friendship are central in ways they were not a half century ago.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, if a woman reached age 25 or 26 without being married, her chance of ever marrying fell quite sharply, and if she did marry at an older age, she had a higher risk of divorce. Today, the social and cultural "best practice" is to delay marriage. For every year that a woman delays marriage into her thirties, her risk of divorce goes down.

It is also more important than it used to be for couples to have enough experience to distinguish lust or infatuation from love. Like it or not, this probably means that hookups will persist as a phase of the life course for people who delay marriage until they are at a place where they are willing and able to invest some serious time in developing a relationship.

These changes in courtship and marriage mean that people are trying to negotiate a relatively new set of questions: How will I deal with my sexual desires and needs in a world where I am not going to partner up permanently until later? How will I make friends with the opposite sex in the way that I need to if I am going to have a successful marriage in a world that no longer relies on gender-specific behaviors to organize personal and work life?

Not all the answers people have so far come up with are helpful—and many are helpful in some ways and dangerous in others. But to form a successful relationship requires playing by different rules than it did 30 or 40 years ago. Playing by the old rules was once a route to a pretty successful marriage. Now it is often the route to an early divorce.

In history, there is no such thing as equilibrium. Every time a society solves one problem, a new one presents itself. The same things that have made a good marriage fairer, more intimate and more beneficial to all its members than ever before in history have also produced more alternatives to marriage and have made an unsatisfactory marriage seem less bearable. The same things that have opened up new opportunities for individuals to cultivate their own potential have created new places where they can sabotage themselves and those around them. But most of the new problems we face today arose in the process of resolving old problems that were worse.

Looked at historically, opportunity and anxiety are two sides of the same coin. We should focus on the new opportunities that have opened up for more egalitarian and beneficial family relationships rather than bemoaning the new risks that inevitably have accompanied the expansion of our choices.