Faces of Jesus: Rembrandt and the incarnation

Two faces fascinated Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) over the course of his long and singular career—his own face and the face of Jesus.

More than 90 self-portraits, spanning almost the entire length of the artist's career, are a visual memoir that is as searching and comprehensive, in its own way, as Augustine's Confessions. Rembrandt's visual meditations on the face of Jesus reflect momentous changes not only in Rembrandt's faith but in how people of his time envisioned Jesus. "Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus," at the Detroit Institute of Arts until February 12, 2012 (previous stops were at the Louvre and the Philadelphia Museum of Art), traces those changes by gathering together 64 Rembrandt paintings, etches and drawings that portray Jesus.

In the two centuries before Rembrandt, depictions of Jesus in northern European art followed established understandings of how Jesus should be portrayed. Two of the models for this visual canon, the Veil of Veronica and the Mandylion of Edessa, were supposed to have been miraculously imprinted with the face of Jesus when they were pressed to his face. A third source is the so-called Lentulus letter that, according to legend, was sent by a certain Publius Lentulus to the Roman senate during Jesus' lifetime. The description of Jesus contained in the letter was considered authoritative:

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

His hair is the color of ripe hazelnut, parted on top in the manner of the Nazarites, and falling straight to the ears but curling further below, with blonde highlights and fanning off his shoulders. He has a fair forehead and no wrinkles or marks on his face, his cheeks are tinged with pink. . . . In sum, he is the most beautiful of all mortals.

In the centuries before Rembrandt, artistic renderings of Jesus followed these models and descriptions very closely, creating a uniformity that seemed to vouch for their authenticity. In them Jesus has a long, narrow nose, a high forehead and eyes that look—especially to the contemporary viewer—almost lifeless. In these depictions Jesus is always looking straight ahead, as if a mere turn of the head would betray an unseemly humanity. The overall effect is that Jesus seems strangely distant from things human. There is a decided flatness about these paintings, as if Jesus could take on two dimensions of human existence but not a third.

In the centuries before Rembrandt, artistic renderings of Jesus followed these models and descriptions very closely, creating a uniformity that seemed to vouch for their authenticity. In them Jesus has a long, narrow nose, a high forehead and eyes that look—especially to the contemporary viewer—almost lifeless. In these depictions Jesus is always looking straight ahead, as if a mere turn of the head would betray an unseemly humanity. The overall effect is that Jesus seems strangely distant from things human. There is a decided flatness about these paintings, as if Jesus could take on two dimensions of human existence but not a third.

Rembrandt's own early work reflects some of these influences. In Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1644), Jesus' long, golden hair fans over his shoulders. His posture is perfect and he is a head taller than anyone else in the scene. As imagined in the Lentulus letter, Jesus is "the most beautiful of all mortals," a kind of superman.

Just four years later, however, in his painting Supper at Emmaus, Rembrandt gives Jesus a different face. His nose is now prominent, his eyes are pensive. No longer does Jesus have the posture of a soldier. His shoulders are rounded and his head is tilted slightly (it is amazing how a mere tilt of the head can communicate humanity). His hair is dark and thick, draping over his shoulders in ringlets. This Jesus is obviously human—and this was something new. From near the beginning of Christian history, the doctrine of the incarnation was consistently affirmed by the church. With Rembrandt's new depictions, the viewer was invited to consider what incarnation actually looked like.

One of the etchings in this exhibit is familiar to me; I have a copy of it in my study. It shows Jesus preaching to a small assembly. A child lies on his belly and draws in the dirt with his fingers, much as a child today might draw on an order of worship with a crayon. A few others gaze off into space, lost in reflection. Most have their eyes riveted on the preacher.

If we, with the crowd, focus on Jesus, we notice nothing about his appearance that sets him apart. There is nothing prepossessing in his stature or countenance. His hands are large—workman's hands, hands that have served long hours. His face could not be called beautiful. I'm reminded of Isaiah's words: "He had no form or majesty that we should look at him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him" (Isa. 53:2). If his figure were put in the crowd of listeners, we might not even notice him.

But if our eyes shift back to the listeners, we appreciate that they see more than this. They know that this is no backwoods faith huckster. On the contrary, this is the one upon whom everything depends. His face is not so ugly that only a mother could love it, but it is so plain that only the faithful can see God in it. And see it they do.

A child once stared at that etching and asked, "Who's that?" I replied, "That's Jesus." "Oh," the child responded, more than a little surprised, "I didn't recognize him." And little wonder. He looks so everyday that it should not surprise us that Rembrandt most likely found models for his portraits of Jesus by wandering the largely Jewish neighborhood of Amsterdam where he lived. In Rembrandt's Amsterdam, using a human model for Jesus was itself a scandal, a scandal that would only be amplified by choosing a Jewish model.

In many pictures that hang in church schoolrooms (or in our mind's eye), Jesus is made to stand apart in his humanity, as if his humanity were somehow different from ours. We are led to believe that if we saw him at a lunch counter or stuck in a traffic jam, we would know him. The human eye would be enough to perceive that this one is different from all others. If Jesus were set apart, we might assume that only a fool would not see the living God in him. We would wonder why so many fools lived at the time Jesus walked the earth, people who had the advantage of seeing him with their own eyes and yet did not acknowledge him. The reason, of course, is that the human eye is not enough. Only the eye of faith can see Jesus Christ.

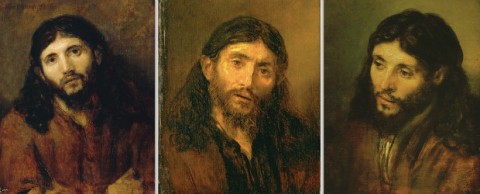

The centerpiece of this exhibit is a series of seven small oil portraits of Jesus (there may have once been an eighth), gathered together for the first time since they stood in Rembrandt's studio more than 350 years ago. The paintings show the face of Jesus from different angles and in various states of mind. The predominant mood in these paintings is meditative, in some way mirroring Rembrandt's pensive self-portraits from this same period. Gone is the Jesus as superman. Gone are the crowds surrounding Jesus. These paintings are a personal face-to-face encounter between an artist and his Savior, both of whom have tasted human sorrow. Two of these paintings were kept in Rembrandt's bedroom, an appropriately intimate place for such personal meditations on canvas.

In the coming weeks countless sermons will strive to express the mystery of the incarnation. After seeing "Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus," I'm sure that no sermon will usher us into that mystery more powerfully than these portraits of Jesus do. In their eloquent silence, these paintings are the most profound witness to the incarnation that I can imagine.