Permission not to pray

We all have seasons when faith rings hollow and prayers seem tinny and meaningless. One such season for me came years ago as I was finishing seminary. At the time my seminary experience had become an almost exclusively intellectual affair. I learned a lot, but not much about praying or living in Christian community—at least not as much as I had hoped.

A dream I had at the time captured what I was going through. I dreamed that my whole body was reduced to a grotesquely huge head. My limbs and torso were miniature and useless—spaghetti noodles on a pencil barrel. As it happened, my head-self was situated in a bucket beside a swimming pool. Someone came along and bumped the bucket into the pool. I was drowning, but with my thin noodle arms and legs I couldn't do anything about it. Bubbling, I sank to the bottom and finally sucked water into my oversized mouth.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I took my dream of drowning to mean that I could not take in any more Christianity for a while. I was suffocating and needed some air. It wasn't a full-blown faith crisis, but I felt like I needed some time away, some time to breathe.

I had a very wise priest. When I asked him for permission to take a brief sabbatical—perhaps six weeks—from church, he said he had seen this sort of thing before and all had turned out well. He told me not to panic. He not only gave me permission to take a sabbatical but granted it with his blessings.

I am not writing an exhortation to skip church. I am writing, rather, about those times when we feel spiritually incapacitated, unable to pray. It is then, perhaps more than at any other time, we need others to pray for us.

I mean the for in two senses. Of course we need others to pray for us in terms of what ails or worries us. We need prayer for the healing of a cancer or for coping with the death of a loved one—or for the return of more robust faith. This is the usual, and highly important, sense in which we think of praying for others. But we also need others to pray for us in the sense of praying in our stead, praying prayers to substitute for our weak or absent prayers.

I've thought of this need recently as two of my closest friends suffered through the worst year of their lives. They have faced acute and deeply troubling family problems. One friend told me he barely manages to keep going to church weekly and to say the Lord's Prayer daily before he (fitfully) drifts off to sleep. The other said he tried to pray, but it only increased his pain. Because God was not answering his prayers for a loved one in desperate need, prayer only made God seem more acutely absent—and less sympathetic or compassionate.

To both of my friends I offered permission and a promise. The permission was permission not to pray, and certainly not to worry if they couldn't pray more or pray somehow "better." Surely God is big enough to understand the extent of their pain and the depth of their injuries. Just as an injured athlete needs to take a break and at the least slow to a limp, my friends could take some time to rest.

The promise was my promise to redouble my own prayers for them and in their place. This is what the church is for; this is why prayer is plural (Jesus prays to "Our Father . . ."). We are all in this together. Like the marines, we will leave no man or woman behind. We will carry our wounded.

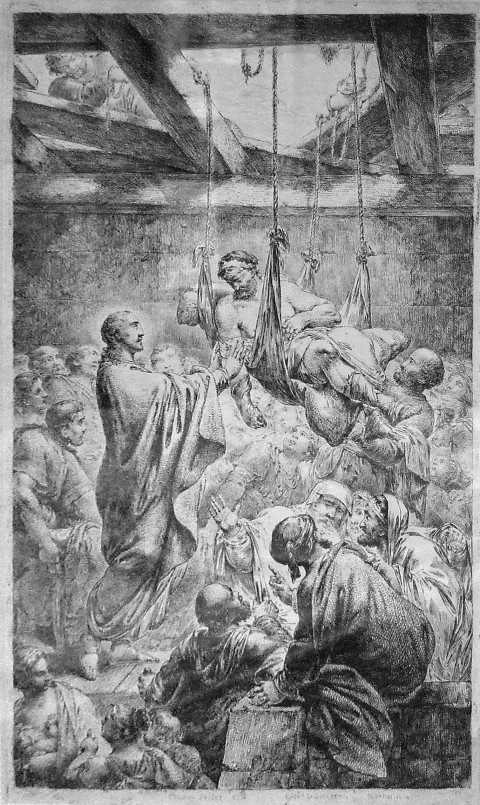

The biblical story that leaps to mind is the healing of the paralytic in Mark 2. Because he cannot carry himself to Jesus for healing, faithful friends bear him. More than that, they climb to the roof over Jesus' head, dig through the roof and present their incapacitated friend to the Messiah. Mark comments, "When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralytic, 'Son, your sins are forgiven.'"

The rest of the story makes it clear that the paralytic was not without his own faith. But he did not depend only on his faith—whether robust or beleaguered. His friends acted in faith for him, in his stead, and because they did the paralytic's faith endured, was strengthened, and in this case quite palpably rewarded.

What about the rest of the story of bucket-headed Rodney, not bereft of faith but weakened in faith? As I recall, my sabbatical lasted only three weeks. I knew that others were praying for me, in both senses of the preposition. Because of my friends' faithfulness when my faith was hindered, I was borne back home all the more swiftly and all the more surely.