Why do we call it 9/11?

Despite all the attention given to remembering the al-Qaeda attacks of September 11, 2001, little attention has been given to one conspicuous aspect--the event has no name.

We don't refer to the issuing of the Magna Carta as 6/15 (the date in 1215 when the document was published). The horrible event of November 22, 1963, is called "the JFK assassination," not 11/22. It's "the Challenger explosion," not 1/28, and "the Oklahoma City bombing," not 4/19. Nor were these events referred to or identified by their date of occurrence in the confusing early days and months after they happened.

Our reference to 9/11 is empty of substance. We aren't explicitly referring to anything about 9/11 except that it was September 11. So what's in a name—or, in this case, what's in no name?

On some fuzzy, subconscious level, it may be that 9/11 caught on because 911 is the emergency phone number—the digits to be dialed in case of extreme crisis. If the attack had occurred on 9/10 or 9/12, perhaps we wouldn't be referring to this disaster by the date.

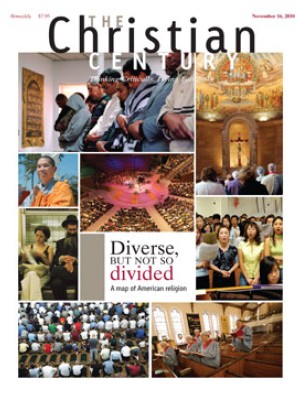

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In any case, nearly a decade after the attack, we are still debating just what it meant or means. Was it a battle in the clash between Islam and Christianity? Was it Islam's declaration of war on the West? Or something else?

What 9/11 means is still debated. And surely it's better that we adopt no name for it than adopt a specious and misleading name. To come up with a name that suggests the attack was a case of Islam versus Christianity, or Islam versus the West, would be a destructive act of misnaming. What happened on that day was an attack by one group of Muslims. All of Islam did not attack the U.S. on September 11 any more than all of Christianity attacked Oklahoma City when the extremist Christian Timothy McVeigh bombed it on April 19, 1995.

But just calling it 9/11 may leave the event too wide open for misinterpretation. It is ominous that more Americans now think of 9/11 as Islam's attack on America than did so in the early days and months following the attack. (In those early days, politicians across the political spectrum were careful to indicate that al-Qaeda was not representative of all of Islam or the Islamic world.)

Failing to name 9/11 effectively may confirm the assumption that "everything changed" on 9/11. In the days and months after 9/11, many pundits declared the death of irony and heralded a day when American culture would become forevermore deeper and more serious. That didn't happen. We're now no less addicted to mass-produced spectacle and obsessive but shallow celebrity culture than we were before 9/11.

Failing to substantially name what happened on 9/11 also helps underwrite the open-endedness of America's war on terrorism. The 9/11 event becomes a blank check for that war, a war that lacks a specific goal.

A military response is not the only or the most important response that 9/11 should elicit. Economic and social problems in the Arab world create important differences between the Arab world and the West. These problems and differences cannot be successfully addressed simply by the blunt club of military means. Many of those problems resonate at the religious level, and if the religions of the world—including Christianity—are to prove to their detractors that religion is not inherently and finally a force for violence, they will have to demonstrate that by means more constructive and complicated than backing one "side" or another militarily.

So let the stunned silence end. It's time to substantially designate the meaning and significance of 9/11. For the sake of peace and the sake of the world, let the real naming begin.