Lives together

It is by living and dying that one becomes a theologian, Martin Luther said. With that comment in mind, we have resumed a Century series published at intervals since 1939 and asked theologians to reflect on their own struggles, disappointments, questions and hopes as people of faith and to consider how their work and life have been intertwined. This article is the fifth in the series.

I am sitting in a guest room of a monastery on Mount Athos in Greece, gathering my thoughts following two conversations with a wonderful monk. We spoke for a bit last evening and again this morning between services in the katholikón. I look forward to further opportunities to visit with him before I hike the rugged trail to another monastery tomorrow morning.

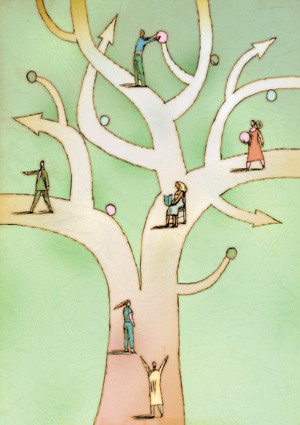

I mention my proximity to these particular blessings because they figure so prominently in shaping my response to the question of how my spiritual journey has unfolded. The availability of a spiritual father and the recovery of holy tradition has made me less inclined to see “my journey” as mine alone and more inclined to appreciate the vertiginous implications of our being the body of Christ, mutually incarnating our way into a collaboratively constructed future.

During the first of my conversations with the Athonite father, I mentioned my struggle with this very essay; I told him that a number of likely reconsiderations had occurred to me, but that I was keen to focus on one, and I also told him that I didn’t want to squander an opportunity to teach myself a thing or two in the process of self-examination, in the writerly process of coming to terms.

This, after all, is one of the ways in which my mind has changed. Some 30 years ago, I still assumed that writers generally wrote to tell us what they knew; these days, I am convinced that the writers I treasure most are men and women who have written in order to see what they had not apprehended beforehand. Rather than understanding their art as a vehicle for transferring known matter from one mind to another, writers (and, ideally, the theologians among them) are men and women who trust their vocations as a way of knowing, or at least as a way of glimpsing the magnitude of what none of us can wholly apprehend.

Presumably, this is what every one of our vocations is capable of doing, as long as we remain true to their attendant gifts. Still, I can imagine how even a writerly vocation might go wrong, how a writer might—for instance—inhibit her own work or hobble his own engagement with language for fear of writing something that didn’t fit with what she or he “believed.” That sort of anxiety strikes me as pretty much the antithesis of faith.

I no longer view the sequential deaths and resurrections of life as matters of the mind, merely. Much as I am grateful for the late recovery of my smudged and recalcitrant nous, I no longer consider that profound intellective faculty in terms of the half measures accommodated by its commonplace translation—mind; and I therefore no longer imagine my metanoia simply as a turn toward better thoughts—as if our Christian faith were a simply propositional faith and not one that demanded em bodiment, incarnation, fruit. You can imagine the sorts of endless splinterings and proliferative schisms that could occur over 2,000 years if one were to mistake Christianity for an idea or for a set of ideas. (In case you missed it, that was sarcasm.)

I was raised in a community that suffered a conflicted relationship with learning. On the one hand, perhaps out of feelings of intellectual inadequacy, our pastors appeared to study a great deal, affected scholarly demeanors and sported honorary degrees. On the other hand, they did not appear entirely comfortable in that posture; they remained largely humorless, responded poorly to criticism and very poorly to questions, especially from the young.

We pored over the King James Bible, albeit selectively, and were treated to a sort of scattergun approach to word study, including both Hebrew and Greek words. For all of that, our pastors seemed to hold—and clearly encouraged—a deep suspicion of education, implying that too much learning could compromise one’s faith. Secular universities were understood to be inherently evil, and the most prestigious sectarian universities were understood to be unduly secularized.

It wasn’t until my days at a state university that I caught on to the poor scholarship that our community’s puffed-up Bible studies involved, and it wasn’t until recently that I have acquired enough Greek language and Jewish theology to mitigate some of the effects of our community’s earnest error.

In retrospect, I would say that we put too little energy into learning who we were and too much energy into saying who we were not—a doomed choice.

In any case, I suppose that it is my sense of salvation itself that has undergone the most dramatic revision.

In his sermon on Solomon’s porch—recorded in the third chapter of Acts—St. Peter alludes quite matter-of-factly to what he calls the chronon apocatastaseos, or the restoration times. While his term apocatastaseos (nowadays more likely to appear in English as apocatastasis) was one borrowed from Aristotle, it proved to be a compelling provocation for most of three centuries of Christian discourse before, for the most part, disappearing from public view.

Such notables as Origen, Evagrios, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Maximos the Confessor, St. Clement of Alexandria and St. Isaak of Syria, among many others, have engaged the notion as indicative of, as St. Paul puts it, God’s will that all men be saved. Even the Italian poet Dante Alighieri avers in his Divine Comedy that, finally, the flames of hell may prove to be nothing other than the glory of God, as experienced by those who have rejected him. St. Isaak of Syria states in no uncertain terms:

He acts towards us in ways He knows will be advantageous to us, whether by way of things that cause suffering, or by way of things that cause relief, whether they cause joy or grief, whether they are insignificant or glorious: all are directed towards the single eternal good, whether each receives judgment or something of glory from Him—not by way of retribution, far from it!—but with a view to the advantage that is going to come from all these things.

The saint says further: