Why I came back to the lectionary

My job as a preacher isn’t to change the game. It’s to run the plays well.

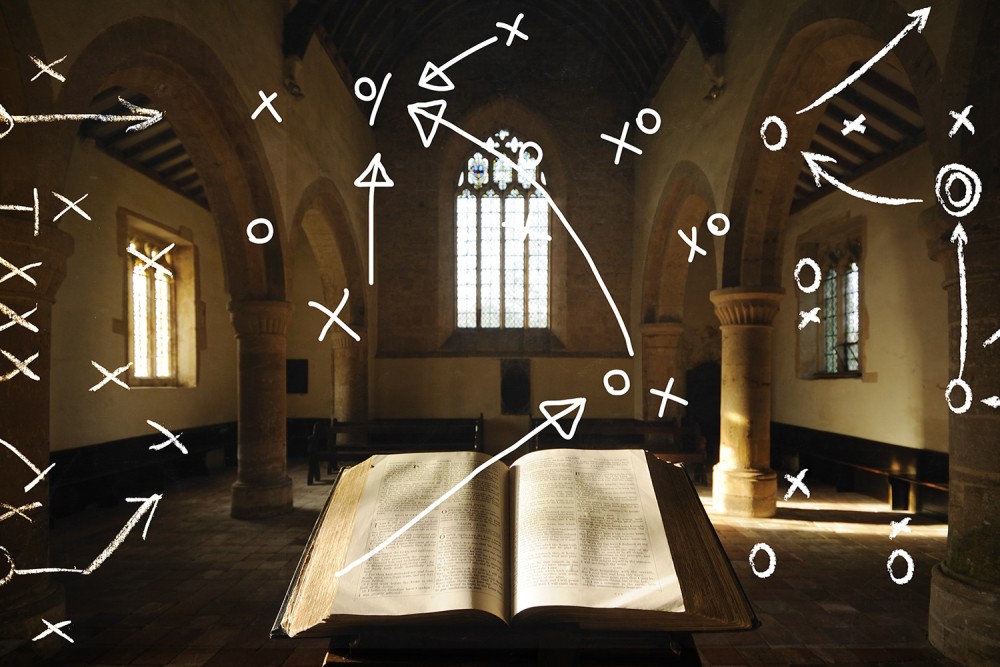

Century illustration (Source images: Getty)

I stopped using the lectionary for a while. Then I went back, and it saved my life.

The plain reason I stopped using it was that I wanted to be original. I have nothing against the lectionary or the church seasons and colors, in fact I love them. I love how the lectionary helps place us in the context of an ongoing story and superimposes the cycle of life onto the calendar year. It puts us in the Bible and the Bible in us. Plus, during weeks when sermon preparation feels like the least urgent part of my pastoral call, I know that I still must prepare something for Sunday—though must we? that’s another topic—and I find in the lectionary a good friend at minimum and sometimes manna from heaven. The moments I have been doing too much or too little are prime for lectionary partnership.

But I also come from the world of hip-hop, which teaches that copying someone else’s style (“biting”) or doing what everyone else is doing can get you an immediate and permanent seat on the bench. “Keep things fresh” is a mantra that courses through my body. Instead of always preaching about joy two Sundays before Christmas, why not do a series or something interesting? Do we have to talk about death in late March? Everyone’s doing that. And shouldn’t I be talking about things that are interesting to these specific people, not what might have been interesting to someone else years ago?