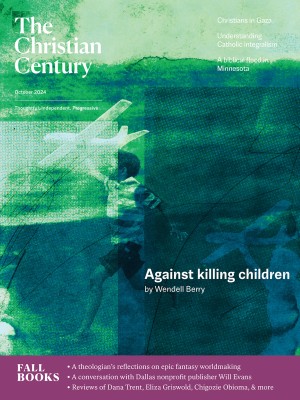

(Illustration by Lilli Carré)

Poetry is close to my heart. I would be lost without its very specific magic, its ability to spark wonder and shock and to open up fresh vistas on life in God. But as W. H. Auden famously says in his elegy for W. B. Yeats, “poetry makes nothing happen.” Now, Yeats’s own poetry is inextricably linked with a particular place (Ireland), and it’s risky to take a line from Auden’s elegy and apply it to poetry more generally. Still, the claim is suggestive and challenging.

In spiritual terms, what can poetry actually do and achieve? And what if its abiding power lies in its doing nothing? I say that not to limit the wider effects of poetry. I’ve no doubt it can stir strong responses at a political or social level. I suspect tyrants fear poets. At the same time, I am excited by the idea that poetry is an art form that can lead us closer to God—who is “no thing” among things—precisely by doing nothing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Not unreasonably, as you read the above you might first ask what I mean by poetry. I don’t propose to offer a definition. I trust that each of us has a reasonably informed idea of what constitutes poetry, an idea which would include the writings of Emily Dickinson, John Donne, T. S. Eliot, and so on. So, what would it mean to say that, for example, Dickinson’s “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers” does nothing and thereby may be especially spiritually valuable?

In Making Nothing Happen, Gavin D’Costa, Ruth Shelton, and their group of poet-theologians suggest that poetry has the potential to open up creative, empty space. This is the sort of space that “invites the harried reader, heckled by all kinds of other discourse—each of which seeks to accomplish some particular end—into a void in which all utilitarian ends are refused and language is celebrated and experienced in all its apophatic, contemplative glory.”

This resonates with me. When I read great poetry like Dickinson’s, I find myself moved beyond utilitarian conceptions of language. In poetry, language is not treated as if it exists to achieve some human consequence, to make me buy a product or even to make me feel or react in a particular way. It doesn’t exist to harry me into a specific political or emotional response. Poetry, unlike so many ways language is used, is precisely a work of resistance to propaganda and populism. Poetry eats propaganda for breakfast. Indeed, as Dickinson herself famously said, “if I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.”

Poetry doesn’t have to be religious to do this. Good poetry has never quite lost its power to sing our deep longing to find sense in a bewildering universe. As Seamus Heaney has suggested, poetry has never been fully secularized. It cannot help but create space for something greater than itself. It is, as Rowan Williams says, “always an act of faith.” I think he means that for all the discipline and skill a poet can bring to wrangling with words, poetry will always be allusive, will always gesture toward mystery. It presents a worked-up example of Simone Weil’s aphorism about “the connections we cannot make.” If poems do not change the outside world, they do, as Williams puts it, “change the landscape of language so that space appears.”

Poetry can help us encounter the mystery at the heart of the matter without being destroyed.

The nothing that poetry does is not the absence of action. Rather it is the fullness of providing space for discovery, imagination, and fresh connection. This space is, I think, not too distant from that spoken of by the anonymous 14th-century English mystic who wrote The Cloud of Unknowing: “But now you will ask me, ‘How am I to think of God himself, and what is he?’ and I cannot answer you except to say, ‘I do not know!’ For with this question you have brought me into the same darkness, the same cloud of unknowing where I want you to be!”

The poems of a Dickinson, Rossetti, or Eliot or of a modern master like Geoffrey Hill can help us to enter into a cloud of unknowing where all our regular, authorized ways of designating and navigating God are placed in question. Indeed, I think that when we dare to embrace poetry’s capacity to make nothing happen, we might come to a richer conception of those things we love to treat as battened down—stuff like doctrine and even the limits of orthodoxy.

In short, poetry can help us dare the depths. Through words it can create a prayer-like attentiveness so that we might dwell in silence and thus address God there. Priest-poet Gerard Manley Hopkins claimed that “the world is charged with the grandeur of God.” As a fellow priest-poet, I want to add that the world is charged with the terror of God—which might just be another way of acknowledging the same thing. Poetry has the robustness to hold us so that we can go far beyond the conventional to the substrate, the ground, from which our human representations of God flow. It can draw us to the mystery at the heart of the matter and help us encounter that mystery without being destroyed. Out of the Babel of words, poets can wrestle truth, love, and justice. God the ineffable, the definitive other and deepest mystery, is made available to the poet through hard-earned word and form.