Stretched between life’s verses

The future is scary: we simply don’t know, and it flies toward us anyway.

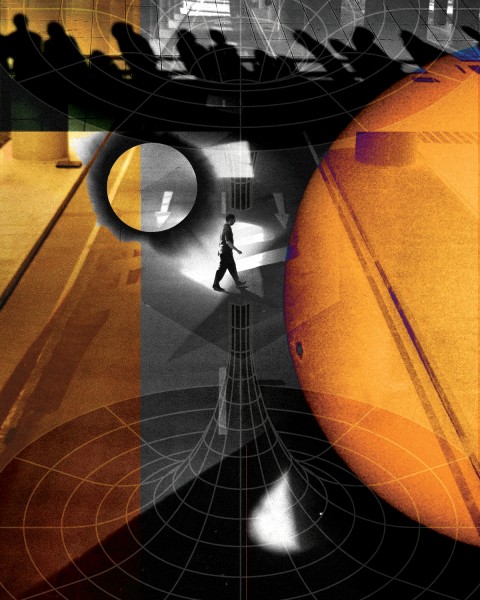

(Century illustration)

Augustine once described the difference between our experience of time and God’s experience as the feeling of being stretched between past, present, and future. He said time, for us, is like singing a song and being caught between recalling what we had sung, singing the words in the moment, and anticipating the words that will come.

As I sit and write this I am anticipating a new season of life, changes that were always coming but were never quite present. And now I can see the first glimmers (or shadows) of change on the horizon. I’ve been thinking of this feeling of being stretched, of trying to be present to the moment even as I hold what has come and what is to be. It’s a feeling I often have writing this column, knowing the world may feel very different in the time between when I write it and when it gets published. Or the gap between writing a sermon on a Wednesday (or Saturday morning) and news that roars in on a Saturday night, or the plans we make in the spring before a very different life greets us in autumn.

But the future always comes, doesn’t it? Metabolism slows, kids become adults, economies shift, people die, wars rage, presidents are voted in and out, change always comes.