The hope I’ve arrived at

I used to put a positive spin on everything. The effort didn’t serve my children—or my own heart.

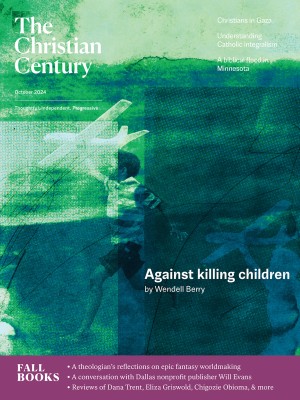

(Photo: D-Keine / iStock / Getty)

Maybe I’m naive to think that parenting young adults was easier in the past than it is now. Maybe the business of launching our beloved babies out into the big wide world has always been fraught and painful. All I know is that this moment—this moment of climate peril, mass shootings, political brokenness, war, economic uncertainty, failing civic institutions, violent and racist rhetoric, and death-dealing loneliness—feels like an especially hard one to navigate as a mother. Specifically, it feels like a hard one to navigate with hope.

When my children were younger, my go-to response when they came to me with fear, anger, or grief about their future was to emphatically contradict them. To offer them a carefully curated version of, “Oh no, it’s not that bad. It could never be that bad—here’s why!” Those conversations routinely drained me, because deep down I knew that I was operating out of panic. I assumed that my faith required me to put a positive spin on even the bleakest things. Also, I wanted to spare my children pain. So I wore myself out bending their lived reality into pretzels to make it prettier, more palatable, and more “Christian.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It took me a long time to recognize that I was serving no one with these efforts. Not God, not my children, and not my own heart. What I was offering my kids was not hope; it was denial. It has taken me even longer to understand that whatever hope entails now—in the shadow of America’s failing democracy, at a time when students coming out of college and even graduate school can no longer find jobs or afford homes, a time when young adults are increasingly opting out of starting families because they are legitimately terrified of climate collapse—it simply cannot entail a Pollyannaish minimization of what is real and true. Even if what is real and true is terrifying.

When my twentysomething children share their sorrows, fears, and frustrations with me now, I try hard to assume a different posture. I try hard to embody a different version of hope.

This version doesn’t flinch away from truth telling. It embraces Jesus’ risky teaching that the truth alone will set us free. Yes, the truth might hurt first. It might hurt a lot. But acknowledging and naming it is the only way forward, especially for those of us who want to bear credible witness to Christ in this moment. We will get nowhere if we pretend that we haven’t done irreparable harm to our planet; or that our political, economic, and civic structures aren’t as bad off as they are; or that our racist, colonialist past isn’t crying out for an honest and humble reckoning. Jesuit priest Walter Burghardt once described contemplation as a “long, loving look at the real.” Sometimes what is real is ghastly. But hope requires that we gaze at the ghastly with heartbroken love, too.

This version makes room for lament. It honors the ancient Christian practice of crying out in grief, rage, horror, and desolation at a world that doesn’t look anything like God’s dream of a peaceable kingdom. It surrenders the privilege that keeps us in denial. It sits in the ashes. It lingers at the cross. It practices reverence at the grave.

Once we recognize that hope can also be palliative, we can weep for what is lost, what is dying, and what we will not get back. We can repent for what we have neglected, abused, betrayed, and killed—out of our ignorance, our greed, our misguided religiosity. We can confess to future generations that we have not stewarded this gorgeous, fragile earth as we ought to, and we can beg their forgiveness. We can recognize the full weight of human failure and finitude and ask God for mercy, wisdom, and repair.

True hope requires sitting in reality’s ashes, gazing at the ghastly with heartbroken love.

This version disentangles love, justice, and goodness from any knowable or predictable results—and chooses love, justice, and goodness anyway. “How would you live differently today if you knew that everything would end tomorrow?” is a question I’ve pondered with my children many times. In truth, we have no idea how much time we have left. As individuals, as a democracy, as a species. Neither do we know how effective our small-scale efforts might be in bringing about meaningful change. I will leave it to the theologians and the scientists to sort out a viable relationship between the climate crisis and the eschaton. Between our vast human folly and the eternal providence of God.

In the meantime, the hope I’ve arrived at now simply compels me to choose the good, the beautiful, the loving, and the just on a daily, minute-by-minute basis—regardless of the results. I will never do this perfectly. But I will make it my goal, and I will encourage my children to make it their goal, too. Who knows, in the cosmic scheme of things, how our tiny acts of resilience, kindness, reconciliation, and reverence will ricochet across the years or generations? Who knows what guises resurrection might yet take? What else is Christianity if not an astonishing commitment to the tiny, the improbable, the fragile, the broken? A mustard seed. A bit of yeast. An alabaster jar. A crucified carpenter.

In her beautiful short piece “a blessing for the lives we didn’t choose,” Kate Bowler asks God to meet us in “the after,” in the place where we never expected to arrive. This is not a place I ever expected to inhabit as a parent when my children were born. But here, too, God is with me and with my children. And so I am learning to pray with Bowler: “Show us a glimmer of possibility in this new constraint, that small truths will be given back to us. We are held. We are safe. We are loved.”