A gospel that admits it’s a false prophecy

One of the most fascinating texts from early modern Europe is the Gospel of Barnabas.

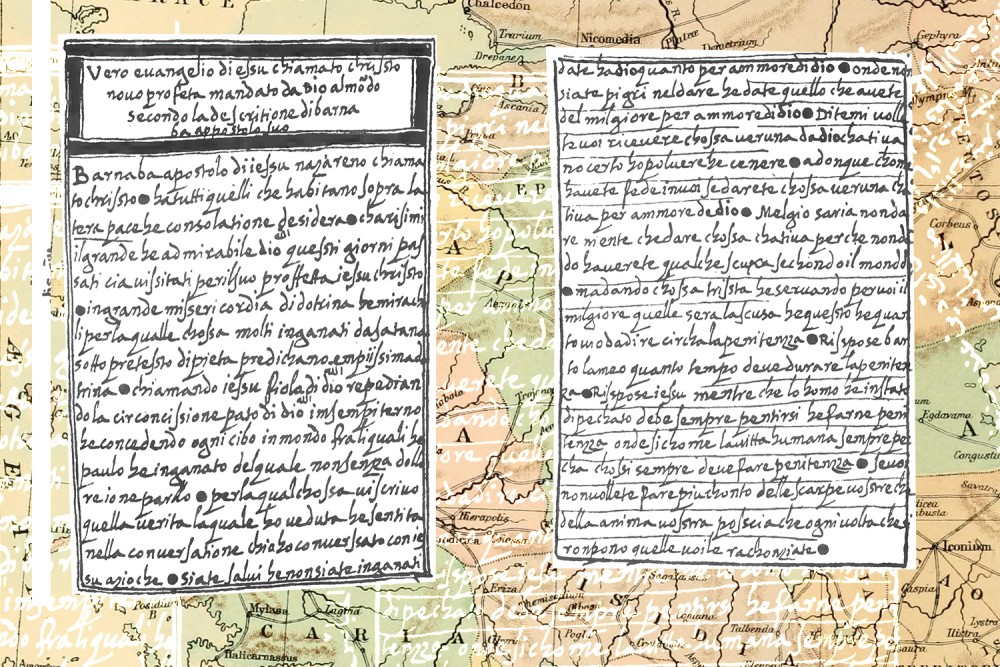

Frontispiece of the Vienna manuscript of the Gospel of Barnabas (Public domain)

Many readers are familiar with the concept of lost or alternative gospels, which were produced so abundantly in the early Christian era. Another gospel, from a much later era, might be unique in Christian literature of any and all eras. Just imagine a gospel composed by Jorge Luis Borges while Umberto Eco held his coat and Neil Gaiman took notes.

The text in question is the Gospel of Barnabas, which in its present form was probably composed in Spanish around 1600. (Every comment about its date and origins is controversial.) It offers a Jesus who in many ways is very close to the canonical figure, except that he repeatedly declares the future coming of a new prophet, who will be Muhammad. Since the late 19th century, Barnabas has become immensely popular in the Islamic world, where it is vital to polemic and proselytizing. As such, it circulates far more widely than any of the more famous alternative gospels that we know in the West.

Barnabas may have originated with the Moriscos, Spanish Muslims who converted at least notionally to Christianity but were expelled from the Spanish possessions in 1609. But the gospel is far more than a simple Muslim apologetic. Throughout this very long text, at every stage we encounter truly subversive themes of deception and illusion, which allegedly permeate all the major faiths.