God’s maternal love

I wonder if what I felt, feared, and learned as a young mother mirrors what God experiences when she tries to feed us.

Photo by miljko / E+ / Getty

Years ago, when my daughter was born, I knew that I wanted to breastfeed her. I had not grown up seeing women nurse their babies, so I spent my entire pregnancy reading books on the subject. At the end of nine months, I figured I was an expert. I also figured that since breastfeeding is a natural process, it would come, you know, naturally.

When the time came to actually do it, though, it only took me about 30 seconds to realize not only that my newborn had not read the books, but that the books were useless in the face of our mutual bafflement. I had no idea how to hold the baby. She had no idea how to latch on. Neither of us knew how to keep her tiny flailing fists out of the way of her frantic little mouth, and neither of us knew how to keep her from choking when the milk let down. The natural business of a mother feeding a child ended up taking weeks of practice, patience, clumsiness, and tears.

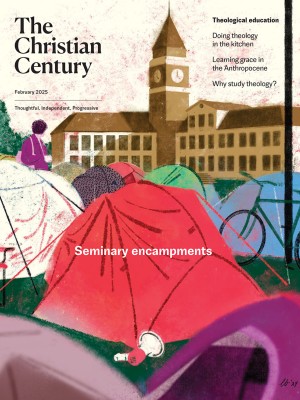

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But over time, we learned. We figured out what to do with our bodies. We developed a rhythm. We nestled into each other, my daughter eagerly drawing the essentials of nutrition, affection, and protection from me, and I in turn—aching with tenderness, urgency, and wild, unbelievable love—sharing my whole self with the little person cocooned in my arms.

Between my two children, I spent about four years of my life breastfeeding. Four years sustaining human lives with my body. Four years glowing with pride and satisfaction when my babies’ cheeks filled out, and their limbs grew strong, and their eyes sparkled, and their bellies swelled with my milk. I learned what it meant to give myself away, to delight in a fullness other than my own, to be nourished by the act of nourishing. To become food.

I was too exhausted as a young mother to think much about the spiritual resonances of my experience. But looking back now, I wonder if what I felt, feared, and learned back then mirrors anything of what God routinely experiences when she tries to feed us. Does God feel the aching desire I felt, to nourish children who persist in baffling self-sabotage? Is God patient when we fumble and thrilled when we latch on? Does God feel pride when we finally begin to fill out? What does God’s maternal joy look like when we consent to take in what she provides? When we grow and flourish under her care?

What do God’s sorrow and terror look like when we do not?

When my daughter was 12 years old, she developed anorexia nervosa, and over the course of several months she stopped eating. The descent was gradual: first, no desserts. Then no carbs. And eventually, no meals. Just bits and scraps. A single grape. One carrot stick. A spoonful of yogurt. Hardly enough to sustain a life.

As the illness progressed, our family dining table became a battlefield. Grocery shopping became an exercise in desperation. For years, every attempt at intervention failed, and my husband and I faced the real prospect that we might lose our little girl.

It’s impossible to express what I felt during that period of my life. All I wanted in the universe—what I would literally have died for—was to feed my daughter, to nurture her back to wholeness. Every time she refused to eat, I panicked, I seethed, I grieved, I begged. I experienced a powerlessness that I hope never to experience again. After all, I was her mother. My primary job was to keep my children fed. How could I fail at job one?

Here again, the spiritual resonances pile up fast. I wish I knew the source of this wonderful phrase, but I have heard it said more than once that Christianity is “the eatingest religion in the world.” Hence the abundance of food metaphors in the Bible. Bread, wine, milk, honey. Fish, figs, manna, quail. Banquets, tables, feasts, receptions. The Bible is filled with stories of a God who longs to feed her hungry children. It is also filled with children who inexplicably turn away from the food she offers.

On the heels of my experiences with my daughter, I can easily imagine the heartbreaking urgency of a divine parent who knows exactly what makes for life and what makes for death—and longs to spare her beloved children the latter. I can well imagine how God grieves and weeps, seethes and pleads, fears and hopes, when we say no to the feasts of love, mercy, justice, and peace she prepares for us. And I can imagine very well how she must wrestle with her own vulnerability, her own powerlessness, every time we turn away from her. The terrible cost of the freedom God has given us to starve ourselves if we so choose.

My daughter eventually recovered, and I will always be grateful for that. But the traumas of our lives also leave scars and shadows. I think I will always feel a rawness in my heart when it comes to my children’s nourishment. I wonder if this is the case for God, too.

There’s an evocative line in Psalm 131, another food metaphor: “But I have calmed and quieted my soul like a weaned child with its mother; my soul within me is like a weaned child.” I’ll confess that when it comes to my spiritual life, I am very rarely “a weaned child.” Most of the time I’m the other kind of child—fierce, frantic, flailing. My face scrunched up, my mouth pursed tight and away, my body clumsily resistant to divine tenderness.

It helps to know that God understands my ambivalence. It helps to know that God’s patience won’t wear thin, no matter how long or how hard I resist. It helps to know that somehow, against all odds, God’s love will coax me back to the food I need. Like a weaned child with her mother, I will be full.