Feeling God in a modernist cathedral-in-progress

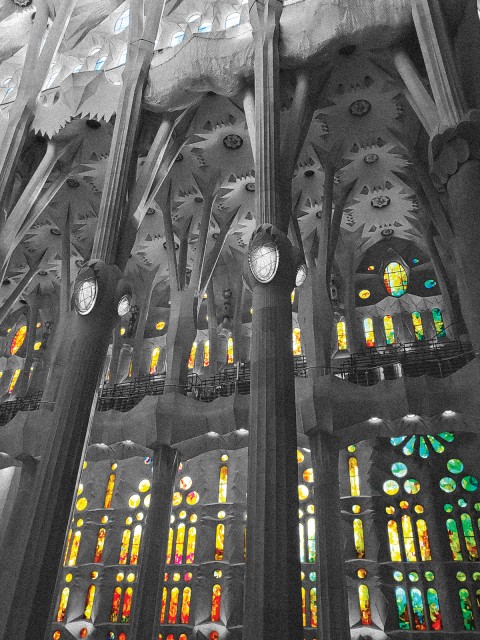

While other churches have filled me with wonder, Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia brought tears to my eyes.

(Century illustration)

On our first day in Barcelona, we went to Sagrada Familia. We walked there from the hotel, waking up earlier than my jet-lagged self would have liked, and around every corner and down every street I expected to see it. From the plane, it seemed like the church towers over the city, the center point to which the whole thing flows. And yet, once we were down within the leafy warren of city streets, we didn’t see the church until we turned the corner into the plaza where it sits, surrounded by construction cranes and mobs of tourists.

If you’re not familiar, Sagrada Familia is the largest unfinished Catholic church in the world, designed by Catalan modernist architect Antoni Gaudi. Gaudi was a lover of sinuous curves, rococo details, and bright, colorful mosaics, and all these are reflected in his masterpiece. The church has been under construction for more than 100 years, starting and stopping with wars and pandemics, and is now probably less than a decade from completion. The last several years, in particular, have been a time of staggering growth: I went once as a kid, some 20 years ago, and my main impressions were of a place that was gray and somewhat dingy—full of scaffolding and concrete bags and the detritus of workers. That wasn’t the church I walked into this April.

The walk over had been gorgeous—utterly cloudless, the spring we had been chasing in Chicago in full swing across the Atlantic. After the indignities of passing through security amid crowds of other tourists, the slight maze of trying to figure out how to actually get into the door we wanted, we walked through a huge door, and suddenly there it was, full of light.